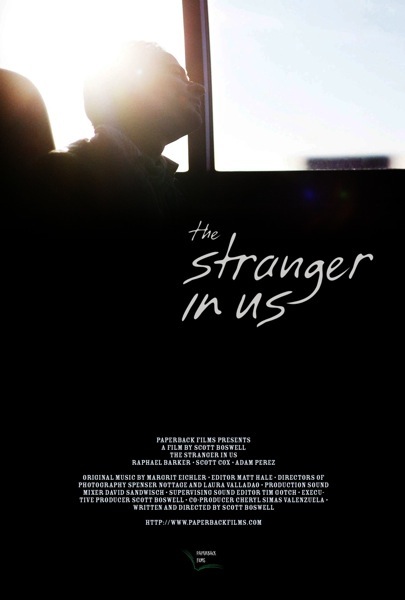

Local filmmaker Scott Boswell may not have set out to make the film he ended up with, but he stands behind the finished product. The Stranger In Us stars Shortbus’ Raphael Barker as Anthony, a young man who moves from Virginia to San Francisco in order to live with his boyfriend Stephen (Scott Cox). When the relationship turns violent, Anthony finds solace in his friendship with Gavin (Adam Perez), an underage street huster. I spoke to Boswell and Barker about the film’s origins, its unique content, and what this year’s San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival says about the future of queer cinema.

San Francisco Bay Guardian: What was your inspiration for The Stranger In Us? Where did the story come from?

Scott Boswell: Ultimately the story ended up being fairly autobiographical. But it started in a different place. Originally — and Raphael knows this because we talked about it — originally, I had intended to do a much more experimental film, kind of a hybrid documentary-narrative, because of my fascination with the Polk Street, Tenderloin area, which I’ve always had since I moved here in the mid ‘90s. I had considered doing a bit of a portrait of the neighborhood, and kind of infusing actors into it, just shooting a lot of footage and seeing what we came up with. There’s a part of me that wishes I had still done that, but in all honesty, I can say that after Raphael expressed some interest in the project, I suddenly felt like it needed to be more narrative in its scope. He didn’t suggest that. It was just my intuition around the project. So I had been talking to him about doing it for months, without even having a complete script, and continued writing it and auditioning actors. Eventually it became much more traditional in terms of its narrative. It became what it is now.

SFBG: And Raphael, what brought you onto the project?

Raphael Barker: Scott. There wasn’t really a finished script and a lot of it was sort of up in the air, but I was just really comfortable with the process and how it evolved, because it was Scott. He and I just hit it off really well.

SFBG: Did you collaborate at all in terms of creating the character of Anthony or writing the script?

SB: Not so much on the script. I run a screenwriting group, here in the city. It’s a small group and we meet a couple times a month, and they had the most impact on the final script. However, there are quite a few places in the script where it suddenly says, “We’re gonna improv here.” And there are definitely scenes where the actors brought the dialog to the scene. Quite a few, actually, especially between his character and Gavin, the street kid. Largely because they had such wonderful chemistry, and I felt like I could trust them to pull it off.

SFBG: Raphael, can you talk about how the improv process was, as an actor?

RB: Scott would set up the scene and then let us go, and just see what happens. And then would make comments as necessary and readjustments. But I felt very free to just let the scene kind of take over and do its thing. I think Scott and I are just both very instinctual. Like, “That’s not how I planned it, but I kind of like it that way. Let’s play with that.” I think especially when you’re talking about Gavin, there was something almost unwritten about our relationship that was allowed to evolve through improv.

SB: Right, because there’s a piece that’s semi-autobiographical that has a place in history, and then there’s the piece that — I feel like Gavin’s character brings a newness, a sort of unfinished, still to be defined ending. There was something about the energy that really brought novelty to the script.

SFBG: You said originally you wanted to showcase this particular neighborhood in your film, and then it became more of a narrative. But it’s still a very San Francisco film. How did you go about capturing that?

SB: The main thing was choosing that location as his studio that he moves into after leaving Stephen, which actually wasn’t true to my experience. However, the person on which Stephen is most based actually lives there, so I kind of flipped it. And the character on whom Gavin is based actually hung out in the Castro, not the Tenderloin. So I flipped those around, and then because the character is so stuck and lost and wandering, he was able to go out into the street and that became the portrait of the neighborhood right there. We had spent a lot of time trying to work out just how we were going to portray that, and ultimately he’s always in the space. I actually did go out and shoot footage of the neighborhood without Raphael, and none of that is in the film.

SFBG: Anthony moves to San Francisco from Virginia, so he’s experiencing the city from an outsider’s perspective. Why did you decide to write him that way? And Raphael, how did that affect your performance?

SB: I think it’s a very common experience in San Francisco. It seems like the majority of people I meet here have migrated from somewhere else. And I think especially for gay men, when we arrive here, we don’t always quite find what we’re expecting, and especially for queer youth, which is an idea that Gavin embodies. I’m very interested in that sort of push-pull between the desire to be in the city of San Francisco and the challenges that you can face when you arrive. So I was interested in exploring that experience, and I’ve found subsequently that quite a few people — they’re almost always gay men — have come to me and said that they relate to that experience. Different generations of men, and different decades of coming here. It seems to be a continuing phenomenon in a way. In that sense, I think it’s very much a San Francisco story, even though it could probably happen in just about any urban area, especially when someone who doesn’t have experience in an urban environment suddenly arrives and is just thrown into it.

RB: I experienced something very similar coming out here to chase after someone I was pretty in love with, and then being dumped like a week and a half after moving here. And just feeling like I didn’t have that orientation anymore, and everything in the city was associated with this person. I’m sure I’ve one of millions of stories of people — with San Francisco being a kind of pilgrimage, then as soon as we get here we complain about it. But we wouldn’t want to be anywhere else, so there’s kind of that love-hate relationship with it. So I could definitely relate to coming out here to be with someone and having all that kind of expectation and hope, and then me kind of losing that central focus and orientation and realizing, “Now what?” I think that’s a theme that’s not just gay or even queer, but it seems like anyone I talk to who comes from a different place has that similar experience. They knew they needed to be out of wherever they were at, but they weren’t sure what they were exactly coming into.

SFBG: The film also deals with an abusive relationship, which is something we don’t see a lot of in queer cinema. I was wondering why you think that is, and also why you wanted to include it in your movie?

SB: I don’t know why it is, but because it is [not often seen] is one of the main reasons I wanted to include it. Hustlers and street kids appear in a lot of gay cinema — and just to go down that tangent for a second — which is why I chose to not make that character the protagonist but a supporting role. In terms of same sex domestic violence, it is an issue that permeates probably just about any community, but I have seen and heard very little about it among same sex couples. There are some things, some things written and there’s an organization in San Francisco called Community United Against Violence that works to combat and end violence. So there are resources out there, but I wanted to explore it because it’s an issue that’s personal for me, on several levels. It’s something that I’ve experienced and it’s also something that I just personally have always cared about. I volunteered to do work at battered women’s shelters in the past—this was actually in Madison, Wisconsin, long before I’d ever had any kind of experience with it. What I find really interesting is the degree to which people don’t really understand it. No one thinks they’re going to enter a relationship like that. I certainly didn’t think so. I thought I understood it.

RB: Much less something that’s so countercultural in some sense.

SB: Yes, exactly.

RB: Like, “Oh, if I can requite this kind of relationship, that’s kind of the end game.”

SB: The thing is you don’t necessarily recognize it when you’re there. People always say, many people say and have said about this film, “Why does he stay? Why doesn’t he leave?” It’s interesting that people continue to not understand that issue, because it’s clearly a very common human experience. So I guess in a sense, that question to me opens up a dialog on the issue that I find very important. I’ve been asked that a lot from people, and so far, that’s only come from the very limited number of people who have seen [the film].

SFBG: Well, without sounding like I’m trying to justify the abuse at all, these characters are complex enough that you get a sense of why they’re together. You can see how they got to that point. How did you go about creating that, and making sure they weren’t too clear cut or one-dimensional?

RB: I think to show just how much we loved each other is one way to do it.

SB: Yeah, that was important. I approached this very much as a character piece. I mean, that’s what interests me as a filmmaker and as a writer. In terms of the kind of genres I might be able to work in, I think it’s an area I probably have more of a knack for. But I think it’s true for any genre you’re working in, you have to rewrite. You have to be able to get down the ideas and the scenes on paper, and then take a look at them and be open to feedback. And assessing where it is that they’re black-and-white or flat and one-dimensional, and trying to create scenes that are more organic and layered. So that’s what we did. Once I knew what the story was, it still took me a good nine months to write the thing before we started shooting.

SFBG: One last, much broader question. How have you seen queer cinema change over the years, and what is the direction that you see it taking?

SB: In just the past few days, in the films that I’ve seen at Frameline this year, I’m very excited. I think queer cinema has gotten better and better. I have reaffirmed my understanding of the necessity of LGBT festivals, because it has definitely gone through phases. There was kind of an indie new queer cinema in the early ‘90s, when Gus Van Sant was coming on the scene, and Gregg Arraki and Todd Haynes. Then in the later ‘90s and maybe early 2000s, it kind of evolved into a lighter, more mainstream cinema, which I actually don’t relate to as much. But the best of them are actually quite good. What I’ve seen more recently, and I hope our film falls into that, is really kind of the ability to look more closely at ourselves and tell our own stories without any kind of concern about the broader mainstream appeal. I know that those kinds of films still exist. I think that independent cinema has gotten to a place where it’s not just simply seeing ourselves portrayed on screen anymore, but it has to be good cinema now.

RB: I saw a lot of films at the Frameline festival two or three years ago when the documentary about the making of Shortbus came out, and it just made me realize that the quality — instead of it being a kind of niche genre, I don’t want to say the opposite of what you’re saying, but I almost see Frameline as becoming redundant, because the films are good enough to stand on their own. They don’t have to be a genre film or a niche or a sexuality genre film. We have to keep working and working toward the specific, and then eventually the specific becomes universal. And I think that’s the beauty of the films that are starting to come out. In the Frameline context, it’s going to actually make it almost redundant because they’re just going to be good films, period. That’s what excites me, because everyone’s experience is so unique. And sure, we’re working within paradigms and categories, but I think it’s just getting better.

SB: It’s interesting looking at where these films fit in in terms of festivals and markets and things like that. I guess what I was trying to say is that I feel like Frameline still needs to be around in order for these films to get shown, because they’re not all going to fit into SF International, they’re not all going to fit into all of the big festivals. The sort of bigger queer films coming out may not need Frameline. There have been a quite a few in recent years: Bad Education, Mysterious Skin, Capote. They’re playing at the bigger festivals or getting distribution without festivals. There is sort of a distinction there. But when I see something like I Killed My Mother, which just kind of knocked me on my ass because I thought it was so brilliant, I don’t know where else I would have seen it.

THE STRANGER IN US

Wed/23, 6:45 p.m., Roxie

Fri/25, 11 a.m., Castro