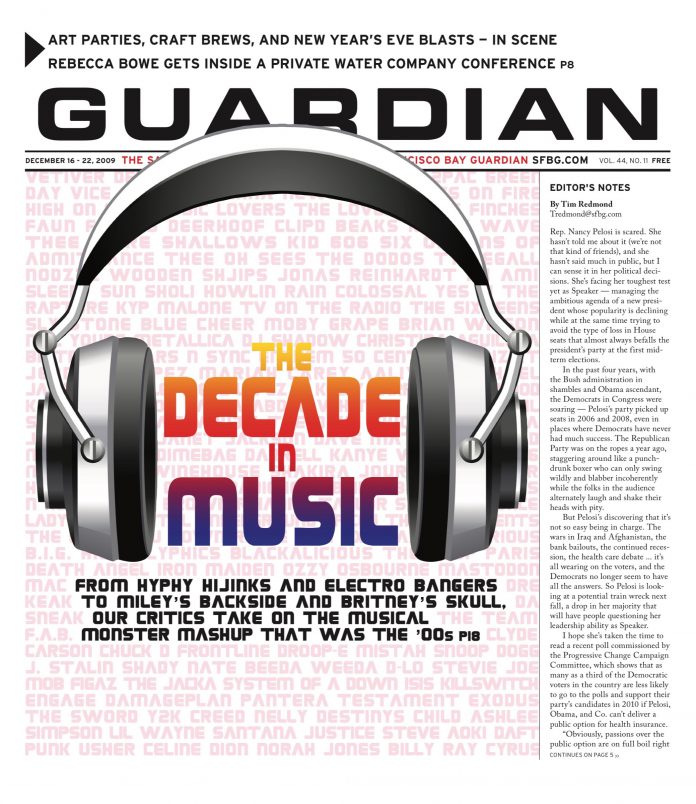

Guardian illustration of Rihana, Lady Gaga, and Britney Spears by Matt Furie and Aiyana Udesen

DECADE IN MUSIC The long-tail slither of the ugly aughts connected umpteen memes: from the rise and fall of Napster to the triumph of "freemium" and the tragedy of the commons, Britney’s vanilla titillations to the haute couture blandishments of Lady Gaga, the funky vulture schematics of Beck to the smoky heroin whispers of Amy Winehouse, the Cristal-fueled corporatism of Jay-Z to Lil Wayne’s codeine-and-tattooed hallucinations — then on to Gwen Stefani, Friendster, TV on the Radio, Justin Timberlake, Franz Ferdinand, Lil Jon, Radiohead, M.I.A., Bonnaroo, the Strokes, Björk, Peaches, the Black Eyed Peas, Justice, Ghostface Killah, Missy Elliot, Pharrell, Animal Collective, Kanye West, and the Libertines …

We, the greedy-eared, were merely supplicants in the age of relativism, competitively rationalizing any product a multinational corporation, small business, or dude in his bedroom surrounded by thrift shop gadgetry marketed to us. So when half-naked Disney Channel tarts got dirty and partied in the U.S.A. with sk8er bois, we loved them as feminists disturbing the status quo and made them VH-1 Divas. When thugs in white tees commanded us to drop it like it’s hot, sold us crack music, and promised to P.I.M.P. us, we hailed them as cultural revolutionaries and gave them Pepsi and Sprite commercials. And when hordes of drive-by truckers took us out, screamed silent shouts, and brought good news for people who love bad news, we granted them a 9.0 rating on Pitchfork and a headline spot at Coachella.

But we should have known better. When positive word-of-mouth and community spirit is codified into "murketing," popular artists become ready-to-sell-out brands, and songs are critiqued through cyberbuzz and SXSW showcases, then even hipster nerds, true-school backpackers, stolid minimalists, and iconoclast idolaters are susceptible to megabucks advertising campaigns and Clear Channel heavy rotation schemes. (Only the overly familiar arc of hype kept its traditional shape in the warped musical universe with his provocative 2000 masterwork The Marshall Mathers LP [Interscope], Eminem twisted shock-jock observations over steroidal keyboard tracks, leading Rolling Stone magazine to dedicate an issue to "The Genius of Eminem." Nine years later, the rapper’s album Relapse scored 59 out of 100 on the reviews aggregator Metacritic.com. Genius: still fleeting, apparently.)

Overshadowing it all was what Time magazine recently called "The Decade From Hell": the hanging chads of the 2000 election, 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the red state-blue state civil wars, the housing bubble. The world did not end, but we swathed ourselves in materialist follies like grief-stricken widows turned desperate housewives, cougars on the rebound. We justified our war on ourselves with a complex financial instrument called "freeconomics." We raped and pillaged our creative communities and paid nothing, and only offered a salutary blog post in return.

Amiri Baraka once called music "The Changing Same." Written in 1966, his essay was an old jazz poet and cultural activist’s valiant attempt to reconcile his beloved "new thing" of free jazz and Black Power with the uplifting, integrationist rhythm and blues of Motown. Four decades later, we can’t even muster Baraka’s conflicted praise for the music world. All is dead. Wired magazine used a photo of the 1937 Hindenburg disaster to portray "The Fall of the Music Industry." Nas declared Hip Hop Is Dead. Indie rock, the soundtrack to our suburban Garden State youth and The Real World: Brooklyn faux-bohemian adventures, went to hell and a Hot Topic outlet. Fuck, man, even George Harrison, J-Dilla, James Brown, Johnny Cash, and Michael Jackson died.

Popism, with its allusions to a global village united under Western capitalism and American exceptionalism, was the philosophy of the day. And pop wasn’t serious music; that term was reserved for late 19th century classical composers and Brian Eno. The rest was noise, MP3s to load onto our iPods, digital squeaks interspersed between gun claps on Grand Theft Auto, and a soundtrack for The Hills and Grey’s Anatomy.

So what did a decade of Auto-Tunin’, guitar-strummin’, and Reason-scrollin’ zombies sound like?

It sounded like glitch, click-hop, IDM, Italo-disco, smooth house, fidget house, blog-house, hard house, Parisian electro-house, South American tech-house, "Body and Soul" house, progressive house, Balearic trance, happy hardcore, dubstep, "beats," wobbly, wonky, funky, nu-rave, darkwave, chillwave, glo-fi, retro soul, neo-soul, swag, crunk, blog rap, favela, booty bass, and B-more. A twitch of niches, each discarded as it surfaced.

On LCD Soundsystem’s brilliant 2003 single "I’m Losing My Edge," James Murphy rattled off a Goldmine catalog full of cult garage bands, No Wave performers, disco DJs and Krautrock novelties, and then sardonically crooned, "You don’t know what you really want."

So what did we really want?

Whatever we desired was at our fingertips. Every song, every trend imaginable was either available on file-sharing programs like Limewire and Soulseek, or could be requested on "private" torrent sites such as Oink and What.cd. A MySpace account yielded streaming music from dozens of your favorite bands, and thousands of friend requests from bands you’ve never heard of.

In this steaming melting pot of microgenres and mixtapes and YouSendIt.com downloads, the finishing line was the current pop zeitgeist, a blessed moment when every Stereogum.com and Nahright.com blog post, and VH-1 Best Week Ever and Current TV Infomania episode was referencing the same thing. Kelly Clarkson sounded just like Avril Lavigne on "Since You’ve Been Gone," but it was so catchy that even Ted Leo covered it. Danger Mouse fused Beatles’ The White Album and Jay-Z’s The Black Album into The Grey Album. Girl Talk made a mixtape of popular crunk tunes and called it Night Ripper; A-Trak did the same thing and called it Dirty South Dance. Vampire Weekend made an album that sounded like Talking Heads, but then so did Clap Your Hands Say Yeah. Dirty Projectors tried to sound like Aaliyah. Fleet Foxes sounded better than My Morning Jacket. When everything is mashed up and boiled, everything sounds the same no matter what you call it.

We cherished catchphrases like "Shake it like a Polaroid picture," a line from OutKast’s sock-hop anthem "Hey Ya!" So it became a Polaroid commercial. Feist’s silly folk-pop charmer "1, 2, 3, 4" became an iPod commercial. Daft Punk’s robo-funk smash "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger" became a Gap commercial. The greatest reward, it seemed, was to become a 30-second advert, a YouTube staple and an American Idol. But anyone who could spam the mainstream earned a booby prize of a Perez Hilton post, a Wikipedia entry, and a top 10 entry in Twitter’s trending topics.

The decade was a stankonia cloud of one-word extinguishers and blueberry boats, milk-eyed menders and bloodthirsty babes, American idiots with cold veins, cryptograms and deadringers, Yankee hotel foxtrots and the danse macabre, and yellow houses and Merriweather Post Pavilions.

And when we finished eating at the Internet trough until our hard drives burst into gigabytes, we were surrounded by a bizarro world of logos, marketing slogans, and impoverished, overworked artists. In turn, we were chewed and swallowed by the gorgon Fame Monster spiking the long tail’s tip. But we didn’t care. We were filled with so much self-loathing and glee at this digital age that had enveloped us, but saw no other way out than to embrace it unthinkingly, with closed eyes, and with no wonder as to whether it could mean something more than the ravenous, all-destroying hunger of the vampire, the undead.

But love is not pop. And we are alive. It’s time to wake up and reclaim our souls. We have a lot of rebuilding to do.