arts@sfbg.com

As a teenager, Emory Douglas was sentenced to 15 months at the Youth Training School in Ontario. It may have been the best thing for him — and the worst thing "the Man" could have done. In the prison printing shop, he discovered a gift for print and collage he would later use as the minister of culture for the Black Panther Party. From 1967 until the party disbanded in the 1980s, his iconic graphic art marked most issues of the newspaper The Black Panther.

Douglas brought the militant chic of the Panther image to the masses, using the newspaper to incite the oppressed to action. In the name of expediency and limited resources, he developed collage tricks to maximize his passionate message. His back-page posters emphasized the Panthers’ community programs, like free breakfast for children, clinics, schools, and arts events. His works presented the struggle with a mixture of empathy and outrage — sometimes direct, sometimes allegorical — that remains innovative and contemporary amid today’s high-tech standards.

In a 1968 salvo called "Position Paper No. 1 on Revolutionary Art," Douglas states: "Revolutionary art is learned in the ghetto from the pig cops on the beat, demagogue politicians, and avaricious businessmen. Not in the schools of fine art. The Revolutionary artist…hears the sounds of footsteps of black people trampling the ghetto streets and translates them into pictures of slow revolts against the slave masters, stomping them in their brains with bullets, that we can have power and freedom to determine the destiny of our community and help to build our world." For 33 years Douglas has stood by these words, working toward a better world for the people.

When Rizzoli published a compendium of Douglas’s posters, broadsheets, and fliers in 2007, a new generation became familiar with the causes of solidarity, liberation, and self-determination he holds dear. He has since had large-scale shows at sites such as L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, while his commitment to social change has led to exhibitions and speaking engagements at Oakland’s New Black World and the sorely-missed Babylon Falling in San Francisco. His interpretation of Toni Morrison’s Bluest Eye for last year’s "Banned and Recovered" show at San Francisco Center of the Book was one of the standout pieces of 2008.

Douglas’ work captures the tragedy and triumph of the disenfranchised, impoverished, and fed up; an eternal struggle against those blessed with power who choose to abuse it. Much like the works of Goya and the words of Hugo, his contribution to that struggle remains immeasurable — not just for what he has created, but for the people he will empower for generations to come.

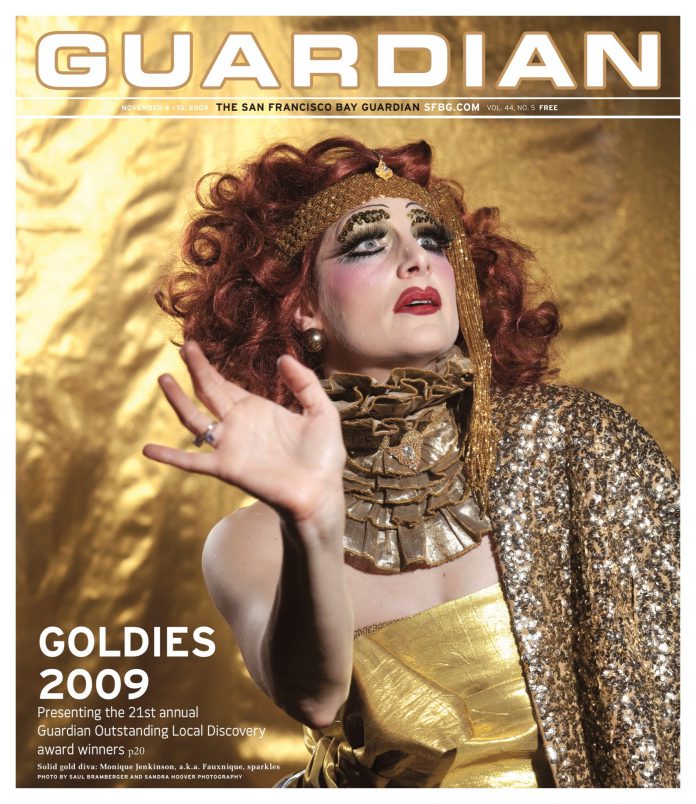

>>GOLDIES 2009: The 21st Guardian Outstanding Local Discovery awards, honoring the Bay’s best in arts