So much to see, independently! Below are some quick reviews of flicks that caught our attention …

SAN FRANCISCO INDEPENDENT FILM FESTIVAL Feb 3–17, most shows $11. Roxie Theater, 3117 16th St., SF. 1-800-838-3006, www.sfindie.com

Bloodied but Unbowed (Susanne Tabata, Canada, 2010) “Nobody tells you that by the time you’re 25 half your friends will be gone” is just one of the memorable lines in Bloodied but Unbowed, director-writer Susanne Tabata’s affectionate and probing doc on the Vancouver punk-hardcore scene. It could have been any scene from around the U.S. in the early 1980s — except most weren’t as politicized and didn’t birth bands like the perpetually touring D.O.A., with speed-demon-in-the-pocket drummer Chuck Biscuits, who the Clash called the best, and the Subhumans, who made an impact with such songs as “Slave to My Dick” and whose vocalist Gerry “Useless” Hannah ended up serving five years in the pen for his involvement in the anarchist group Direct Action. Culling telling quotes from the musicians, managers, and knowledgeable onlookers like Jello Biafra, Henry Rollins, and Duff McKagen, Tabata contextualizes the scene up north, while also capturing the moment with the still-vital music, genuine-article photos and footage from Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue (1980), and those ironclad anecdotes, ending with the images of a road-worn D.O.A. and an encounter with the vanquished hope of the punk scene, Art Bergmann. What came after hardcore? Heroin is the bittersweet, inevitable punch line. But as narrator Billy Hopeless of the Black Halos offers at Bloodied but Unbowed‘s close, the memories and the music survive — and continue to inspire others to write their own chapters. Feb. 11 and 14, 7 p.m. (Kimberly Chun)

We Are What We Are (Jorge Michel Grau, Mexico, 2010) Hewn from the same downbeat, horror-in-the-cruddy-apartment-next-door fabric as 2008’s Let the Right One In, Mexican import We Are What We Are is a disturbing, well-crafted peek into the grubby goings-on of a family of urban cannibals. In the opening minutes, the patriarch collapses and dies in a shopping center; the rest of writer-director Jorge Michel Grau’s film follows the frantic actions of his widow and three kids, notably oldest son and apparent heir-to-the-hunt Alfredo (Francisco Barreiro), who seems way to timid to become the resident Leatherface. With Lady MacBeth-ish sis Sabina (Paulina Gaitán) urging him on — and volatile younger brother Julián (Alan Chávez) doing his best to blow the family’s tenuously-held cover — Alfredo grapples with the gory task at hand. (And I do mean gory.) If you miss this must-see at IndieFest (it’s sure to be a hot ticket), stay tuned for a theatrical release later in 2011. Fri/4, 7 p.m. (Eddy)

The Drummond Will (Alan Butterworth, U.K., 2010) For a quirky, fast-paced comedy, The Drummond Will has a high body count. It’s a mystery in the vein of Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz (2007), but it’s a much more subtle enterprise overall. Straight-laced Marcus (Mark Oosterveen) and charming Danny (Phillip James) travel from the city to the country for their father’s funeral. They soon learn that they stand to inherit his house, which — as it turns out — comes with a set of bizarre complications. Shot in black-and-white, The Drummond Will transitions seamlessly from fish-out-of-water comedy to bloody whodunit. As the deaths escalate, so do the laughs. Because, yes, sometimes it’s funny when people keep dying. I don’t know why the English seem to have a particular talent for gallows humor — the aforementioned Hot Fuzz, 2008’s In Bruges, the original Death at a Funeral (2007) — but let’s be glad they do. And here’s hoping first-time director Alan Butterworth (who co-wrote the film with Sam Forster) has more farce up his sleeve. Fri/4, 7 p.m.; Sun/6, 2:30 p.m. (Louis Peitzman)

Food Stamped (Shira Potash and Yoav Potash, U.S., 2010) Indeed, this is a doc by and about a Berkeley couple who temporarily set aside their Whole Foods-y ways and take the “food stamp challenge,” spending no more than $50 on a week’s worth of groceries (roughly $1 per meal, they figure). And they’re gonna eat only healthy meals, dammit, if they have to dumpster-dive to do it. But Food Stamped is, thankfully, not a self-righteous yuppie safari into po’ town — the Potashs’ experiment provides the framework for an investigation into ways diets could be improved among lower-income families, including visits to farmers’ markets and a farm in Maryland where food is grown for an entire school system. At a slim 60 minutes, Food Stamped is the ideal length to make its point succinctly, without getting preachy — though (and the filmmakers acknowledge this) their food-stamp project is merely a temporary stunt designed to open the eyes of those who’ve never actually needed food stamps to survive. These IndieFest screenings are copresented by the San Francisco Food Bank, which will be accepting donations on-site. Feb. 13, 4:45 p.m.; Feb. 15, 7 p.m. (Cheryl Eddy)

Free Radicals (Pip Chodorov, France, 2010) There’s a paradox at the core of Pip Chodorov’s feature, in that it employs perhaps the most commonplace and programmatic form of contemporary commercial moviemaking — documentary — to explore perhaps the most unique and expressive manifestation of film: experimental cinema. Free Radicals takes its title from a film by Len Lye, and one of the best aspects of Chodorov’s approach is that it doesn’t mercilessly chop up avant-garde works in the service of generic contemporary montage. He’s willing to show a work such as Lye’s film in its entirety, without intrusive voice-over. Chodorov is the son of filmmaker Stephan Chodorov, and his familiar and familial “home movie” approach to presentation is both an asset and a liability. It’s helpful in terms of firsthand and sometimes casual access to his subjects — he largely draws from and focuses on a formidable, if orthodox male, canon: Stan Brakhage, Robert Breer, Peter Kubelka. But it also opens the door for a folksy first-person approach to narration that can err on the side of too-cute. It’s subtitle — A History of Experimental Cinema — to the contrary, Free Radicals functions best as a celebration or appreciation of some notable and vanguard filmmakers and their efforts, rather than as an overview of experimental film. Feb. 13, 8:30 p.m.; Feb. 17, 7 p.m. (Johnny Ray Huston)

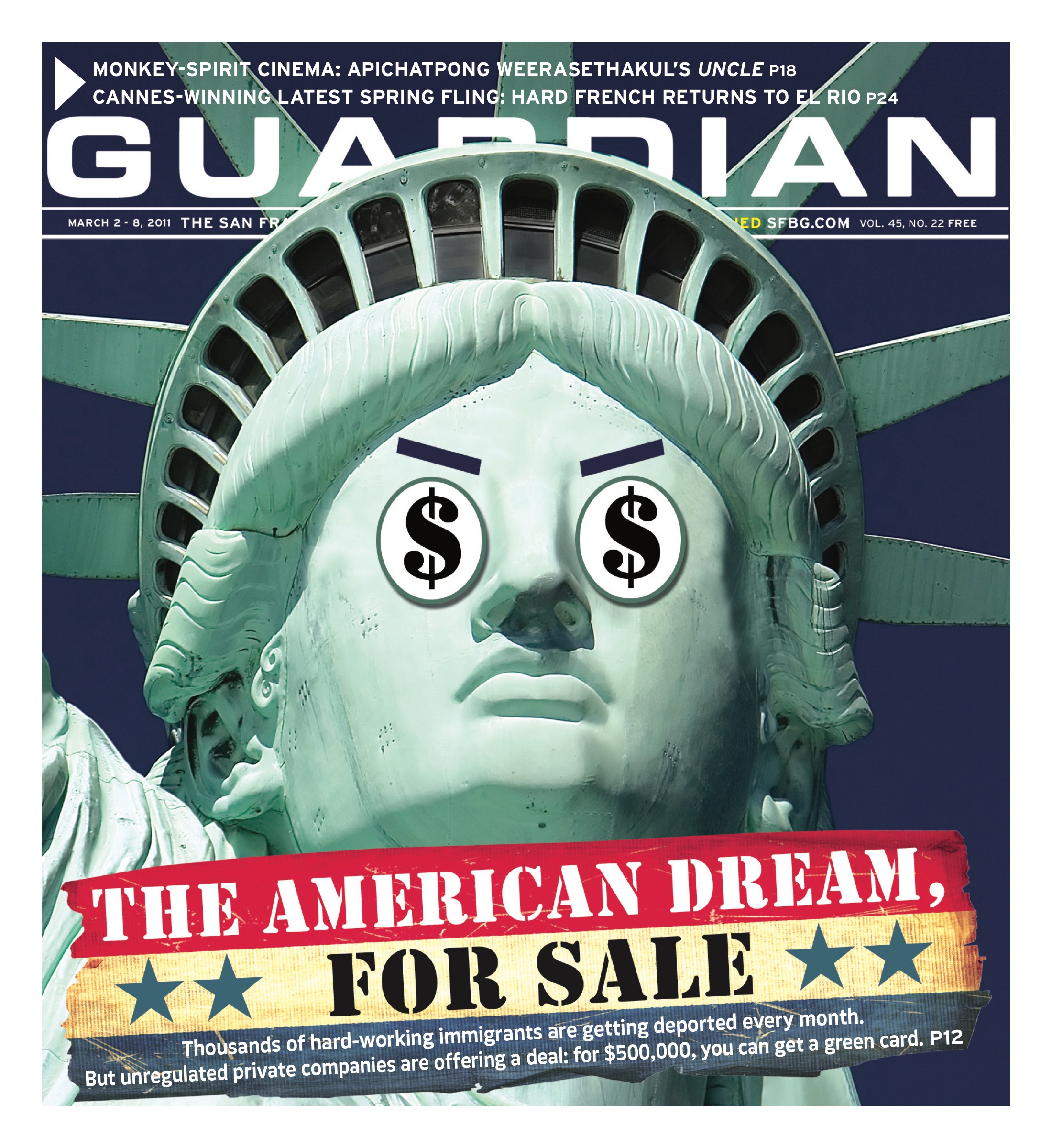

Kaboom (Gregg Araki, U.S.-France, 2010) Gregg Araki’s crackerjack teen sex romp is pure verve — a return to devil-may-care form for fans of The Doom Generation (1995) and Nowhere (1997). Kaboom is right: besides sneaking under the blue velvet rope for a classical mindfuck death trip (there’s even a good part for Jennifer Lynch), Araki and his winning cast let loose a fusillade of dorm-room chatter that runs metaphorical language to its limits. The cult-bidden mystery is too squarely accounted for, but then Kaboom is really as much The Palm Beach Story (1942) as Twin Peaks. Our coed heroes are Stella (Haley Bennett) and Smith (Thomas Dekker), and they’re the only platonic thing in the movie. Taken with Araki’s lasting affection for 1990s culture jamming, this rock-solid friendship is actually quite touching, but Kaboom works best when sliding up and down the Kinsey scale, huffing comic book paranoia for the fun of it. Thurs/3, 7 p.m. (Max Goldberg)

Mars (Geoff Marslett, U.S., 2010) Thanks to Mars, the question “Can mumblecore survive in outer space?” has been answered. (And it’s actually less annoying out there than it is on Earth!) Austin, Texas, writer-director Geoff Marslett’s rotoscope-animated tale follows three astronauts (including m-core heavy Mark Duplass) on a Mars mission, two of whom(Duplass and Zoe Simpson) spark romantically en route. Meanwhile, a solo robot delegation lands ahead of them, discovering new life forms and new emotions, as it sparks romantically, á la Wall-E (2008), with a Mars explorer thought lost a decade before. All the squee gets a little dippy toward the end, but the contrast between slacker and sci-fi genres mostly works. Added points for casting Texas hero Kinky Friedman as the POTUS; Giant Sand’s Howe Gelb did the film’s music and plays the sarcastic head of mission control. Fri/4, 9:15 p.m.; Mon/7, 7 p.m. (Eddy)

Special Treatment (Jeanne Labrune, France, 2010) Let’s get this out of the way first: Isabelle Huppert can do no wrong. That’s not to say she doesn’t occasionally pick terrible projects — she’s just never the thing that’s wrong with them. Special Treatment isn’t so much terrible as it is terribly misguided, contrasting the worlds of psychiatry and prostitution with broad, cartoonish strokes. Huppert plays Alice, a lady of the night who’s thinking about giving up the trade. I don’t blame her; the clients Special Treatment presents her with are the dullest of perverts. One wants her to dress up like a Japanese schoolgirl with a teddy bear and a giant lolly. Another goes the collar and dog bowl route. It’s 2011 — can’t we be a bit more creative with our fetishes? On the opposite end, there’s disenchanted therapist Xavier (Bouli Lanners). And wouldn’t you know it? His patients are photocopies from psychiatry textbooks. There’s a point to be made about the link between paying for sex and paying for someone to listen, but Special Treatment lacks the depth to drive it home. Sat/5 and Feb. 9, 7 p.m. (Peitzman)

Superstonic Sound: The Rebel Dread (Raphael Erichsen, U.K., 2010) “Everything I am came out of music,” says Don Letts — the second-generation Jamaican British DJ, director, and entrepreneur credited with turning punks on to reggae in the late 1970s — in this documentary about his life and work. Much like his contemporary, the late Malcolm McLaren, Letts was a cultural cross-pollinator, working in different mediums while encouraging subcultures to feedback into and off of each other to create something explosive and new. While this serviceable doc lets Letts himself retrace ground that’s been extensively covered elsewhere (it’s worth noting, though, that nearly all the archival footage used was shot by Letts himself), the scenes with his formerly estranged son, who’s also a DJ, are tender and unexpected. Feb. 12, 7 p.m.; Feb. 16, 9:15 p.m. (Matt Sussman)

Transformation: The Life and Legacy of Werner Erhard (Robyn Symon, U.S., 2010) The last thank you in the end credits of this documentary, in bold, is for Werner Erhard. The exiled former est leader and “personal growth” preacher or pioneer should thank director Robyn Symon — I think? – for Transformation, since it’s a 77-minute advertisement for him. Certainly, Erhard is a potentially rich choice in terms of subject matter, but very early on, it’s clear that Symon is out to paint a romantic, positive portrait: testimonials on his behalf are coupled with a low-volume acoustic guitar musical backdrop, and Erhard is even interviewed on the beach. Every once in a while an offhand moment — such as a brief mention of Scientology figurehead L. Ron Hubbard’s predatory view of Erhard — disrupts the soothing flow and opens the possibility of a broader, critical look at the “personal growth” phenomenon. (For the most part, it’s only been dramatized, usually through parody, in films such as 1999’s Magnolia and 1995’s Safe.) As a cultural and even historical figure, Erhard is worthy of an appraisal that’s neither enraptured nor utterly damning. This isn’t it. Thurs/3, 9:15 p.m.; Sat/5, 7 p.m.; Tues/8, 9:15 p.m. (Huston)

Worst in Show (Don Lewis, U.S., 2010) All films about animals in the competitive arena must acknowledge the fundamental truth that the animals themselves are nowhere near as entertaining as their owners. A dog just wants to play, eat, crap, sleep, and maybe have its belly rubbed. The dog’s owner, on the other hand, wants other things — titles, media attention, perhaps an endorsement deal — because they have convinced themselves (as they must convince the judges, and to some degree, the public) that their dog does not just want to play, eat, crap, sleep, and maybe have its belly rubbed. No! Their dog is special. Doc Worst in Show understands this basic drama and finds plenty of eager players in the canine and bipedal contenders, both new and returning, at Petaluma’s annual Ugliest Dog in the World Competition. Amid all the patchy fur, bad eyes, underbites, and malformed legs, it’s the big hearts and outsized egos that truly stand out in this portrait of pageant motherhood at its most extreme. Feb. 9, 9:15 p.m.; Feb. 13, 2:30 p.m. (Sussman)

Je T’aime, I Love You Terminal (Dani Mankin, Israel, 2010) It’s unfair to judge a film by its title, but Je t’aime, I Love You Terminal lets you know exactly what you’re in for. This twee indie romance is Before Sunrise (1995) meets Once (2006) meets every other twee indie romance you’ve ever seen. The film is more mediocre than it is bad, exploring the single-day love affair between two strangers stranded in Prague. Ben is moving from Israel to New York to marry the one that got away. Naturally, he also sings and plays guitar. Emily, an impulsive free spirit, teaches Ben a valuable lesson about living in the moment. Saying this story has been done before is an understatement: Je t’aime packs on indie cliché after indie cliché, without really bothering to develop Ben or Emily into interesting characters on their own. This is a retread without anything to distinguish it from the rest, dragging it down from shrug-worthy to eye-rolling. Feb. 12, 4:45 p.m.; Feb. 14, 9:15 p.m. (Louis Peitzman)