steve@sfbg.com

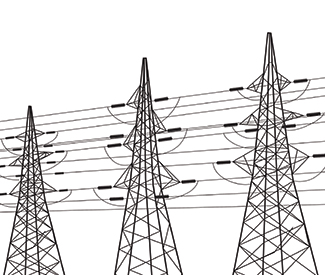

Save the world, work less. That dual proposition should have universal appeal in any sane society. And those two ideas are inextricably linked by the realities of global climate change because there is a direct connection between economic activity and greenhouse gas emissions.

Simply put, every hour of work we do cooks the planet and its sensitive ecosystems a little bit more, and going home to relax and enjoy some leisure time is like taking this boiling pot of water off the burner.

Most of us burn energy getting to and from work, stocking and powering our offices, and performing the myriad tasks that translate into digits on our paychecks. The challenge of working less is a societal one, not an individual mandate: How can we allow people to work less and still meet their basic needs?

This goal of slowing down and spending less time at work — as radical as it may sound — was at the center of mainstream American political discourse for much of our history, considered by thinkers of all ideological stripes to be the natural endpoint of technological development. It was mostly forgotten here in the 1940s, strangely so, even as worker productivity increased dramatically.

But it’s worth remembering now that we understand the environmental consequences of our growth-based economic system. Our current approach isn’t good for the health of the planet and its creatures, and it’s not good for the happiness and productivity of overworked Americans, so perhaps it’s time to revisit this once-popular idea.

Last year, there was a brief burst of national media coverage around this “save the world, work less” idea, triggered by a report by the Washington DC-based Center for Economic and Policy Research, entitled “Reduced Work Hours as a Means of Slowing Climate Change.”

“As productivity grows in high-income, as well as developing countries, social choices will be made as to how much of the productivity gains will be taken in the form of higher consumption levels versus fewer work hours,” author David Rosnick wrote in the introduction.

He notes that per capita work hours were reduced by 50 percent in recent decades in Europe compared to US workers who spend as much time as ever on the job, despite being a world leader in developing technologies that make us more productive. Working more means consuming more, on and off the job.

“This choice between fewer work hours versus increased consumption has significant implications for the rate of climate change,” the report said before going on to study various climate change and economic growth models.

It isn’t just global warming that working less will help address, but a whole range of related environmental problems: loss of biodiversity and natural habitat; rapid depletion of important natural resources, from fossil fuel to fresh water; and the pollution of our environment with harmful chemicals and obsolete gadgets.

Every day that the global workforce is on the job, those problems all get worse, mitigated only slightly by the handful of occupations devoted to cleaning up those messes. The Rosnick report contemplates only a slight reduction in working hours, gradually shaving a few hours off the week and offering a little more vacation time.

“The paper estimates the impact on climate change of reducing work hours over the rest of the century by an annual average of 0.5 percent. It finds that such a change in work hours would eliminate about one-quarter to one-half of the global warming that is not already locked in (i.e. warming that would be caused by 1990 levels of greenhouse gas concentrations already in the atmosphere),” the report concludes.

What I’m talking about is something more radical, a change that meets the daunting and unaddressed challenge that climate change is presenting. Let’s start the discussion in the range of a full day off to cutting our work hours in half — and eliminating half of the wasteful, exploitive, demeaning, make-work jobs that this economy-on-steroids is creating for us, and forcing us to take if we want to meet our basic needs.

Taking even a day back for ourselves and our environment will seem like crazy-talk to many readers, even though our bosses would still command more days each week than we would. But the idea that our machines and other innovations would lead us to work far less than we do now — and that this would be a natural and widely accepted and expected part of economic evolution — has a long and esteemed philosophical history.

Perhaps this forgotten goal is one worth remembering at this critical moment in our economic and environmental development.

HISTORY LESSON

Author and historian Chris Carlsson has been beating the “work less” drum in San Francisco since Jimmy Carter was president, when he and his fellow anti-capitalist activists decried the dawning of an age of aggressive business deregulation that continues to this day.

They responded with creative political theater and protests on the streets of the Financial District, and with the founding of a magazine called Processed World, highlighting how new information technologies were making corporations more powerful than ever without improving the lives of workers.

“What do we actually do all day and why? That’s the most basic question that you’d think we’d be talking about all the time,” Carlsson told us. “We live in an incredibly powerful and overarching propaganda society that tells you to get your joy from work.”

But Carlsson isn’t buying it, noting that huge swaths of the economy are based on exploiting people or the planet, or just creating unproductive economic churn that wastes energy for its own sake. After all, the Gross Domestic Product measures everything, the good, the bad, and the ugly.

“The logic of growth that underlies this society is fundamentally flawed,” Carlsson said. “It’s the logic of the cancer cell — it makes no sense.”

What makes more sense is to be smart about how we’re using our energy, to create an economy that economizes instead of just consuming everything in its path. He said that we should ask, “What work do we need to do and to what end?”

We used to ask such questions in this country. There was a time when working less was the goal of our technological development.

“Throughout the 19th century, and well into the 20th, the reduction of worktime was one of the nation’s most pressing issues,” professor Juliet B. Schor wrote in her seminal 1991 book The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. “Through the Depression, hours remained a major social preoccupation. Today these debates and conflicts are long forgotten.”

Work hours were steadily reduced as these debates raged, and it was widely assumed that even greater reductions in work hours was all but inevitable. “By today, it was estimated that we could have either a 22-hour week, a six-month workyear, or a standard retirement age of 38,” Schor wrote, citing a 1958 study and testimony to Congress in 1967.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, declining work hours leveled off in the late 1940s even as worker productivity grew rapidly, increasing an average of 3 percent per year 1948-1968. Then, in the 1970s, workers in the US began to work steadily more hours each week while their European counterparts moved in the opposite direction.

“People tend to think the way things are is the way it’s always been,” Carlsson said. “Once upon a time, they thought technology would produce more leisure time, but that didn’t happen.”

Writer David Spencer took on the topic in a widely shared essay published in The Guardian UK in February entitled “Why work more? We should be working less for a better quality of life: Our society tolerates long working hours for some and zero hours for others. This doesn’t make sense.”

He cites practical benefits of working less, from reducing unemployment to increasing the productivity and happiness of workers, and cites a long and varied philosophical history supporting this forgotten goal, including opposing economists John Maynard Keynes and Karl Marx.

Keynes called less work the “ultimate solution” to unemployment and he “also saw merit in using productivity gains to reduce work time and famously looked forward to a time (around 2030) when people would be required to work 15 hours a week. Working less was part of Keynes’s vision of a ‘good society,'” Spencer wrote.

“Marx importantly thought that under communism work in the ‘realm of necessity’ could be fulfilling as it would elicit and harness the creativity of workers. Whatever irksome work remained in realm of necessity could be lessened by the harnessing of technology,” Spencer wrote.

He also cited Bertrand Russell’s acclaimed 1932 essay, “In Praise of Idleness,” in which the famed mathematician reasoned that working a four-hour day would cure many societal ills. “I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in modern industrial countries is quite different from what always has been preached,” Russell wrote.

Spencer concluded his article by writing, “Ultimately, the reduction in working time is about creating more opportunities for people to realize their potential in all manner of activities including within the work sphere. Working less, in short, is about allowing us to live more.”

JOBS VS. WORK

Schor’s research has shown how long working hours — and the uneven distribution of those hours among workers — has hampered our economy, hurt our environment, and undermined human happiness.

“We have an increasingly poorly functioning economy and a catastrophic environmental situation,” Schor told us in a phone interview from her office at Boston College, explaining how the increasingly dire climate change scenarios add urgency to talking about how we’re working.

Schor has studied the problem with other researchers, with some of her work forming the basis for Rosnick’s work, including the 2012 paper Schor authored with University of Alabama Professor Kyle Knight entitled “Could working less reduce pressures on the environment?” The short answer is yes.

“As humanity’s overshoot of environmental limits become increasingly manifest and its consequences become clearer, more attention is being paid to the idea of supplanting the pervasive growth paradigm of contemporary societies,” the report says.

The United States seems to be a case study for what’s wrong.

“There’s quite a bit of evidence that countries with high annual work hours have much higher carbon emissions and carbon footprints,” Schor told us, noting that the latter category also takes into account the impacts of the products and services we use. And it isn’t just the energy we expend at work, but how we live our stressed-out personal lives.

“If households have less time due to hours of work, they do things in a more carbon-intensive way,” Schor said, with her research finding those who work long hours often tend to drive cars by themselves more often (after all, carpooling or public transportation take time and planning) and eat more processed foods.

Other countries have found ways of breaking this vicious cycle. A generation ago, Schor said, the Netherlands began a policy of converting many government jobs to 80 percent hours, giving employees an extra day off each week, and encouraging many private sector employers to do the same. The result was happier employees and a stronger economy.

“The Netherlands had tremendous success with their program and they’ve ended up with the highest labor productivity in Europe, and one of the happiest populations,” Schor told us. “Working hours is a triple dividend policy change.”

By that she means that reducing per capita work hours simultaneously lowers the unemployment rate by making more jobs available, helps address global warming and other environmental challenges, and allows people to lead happier lives, with more time for family, leisure, and activities of their choosing.

Ironically, a big reason why it’s been so difficult for the climate change movement to gain traction is that we’re all spending too much time and energy on making a living to have the bandwidth needed to sustain a serious and sustained political uprising.

When I presented this article’s thesis to Bill McKibben, the author and activist whose 350.org movement is desperately trying to prevent carbon concentrations in the atmosphere from passing critical levels, he said, “If people figure out ways to work less at their jobs, I hope they’ll spend some of their time on our too-often neglected work as citizens. In particular, we need a hell of a lot of people willing to devote some time to breaking the power of the fossil fuel industry.”

That’s the vicious circle we now find ourselves in. There is so much work to do in addressing huge challenges such as global warming and transitioning to more sustainable economic and energy systems, but we’re working harder than ever just to meet our basic needs — usually in ways that exacerbate these challenges.

“I don’t have time for a job, I have too much work to do,” is the dilemma facing Carlsson and others who seek to devote themselves to making the world a better place for all living things.

To get our heads around the problem, we need to overcome the mistaken belief that all jobs and economic activity are good, a core tenet of Mayor Ed Lee’s economic development policies and his relentless “jobs agenda” boosterism and business tax cuts. Not only has the approach triggered the gentrification and displacement that have roiled the city’s political landscape in the last year, but it relies on a faulty and overly simplistic assumption: All jobs are good for society, regardless of their pay or impact on people and the planet.

Lee’s mantra is just the latest riff on the fabled Protestant work ethic, which US conservatives and neoliberals since the Reagan Era have used to dismantle the US welfare system, pushing the idea that it’s better for a single mother to flip our hamburgers or scrub our floors than to get the assistance she needs to stay home and take care of her own home and children.

“There is a belief that work is the best form of welfare and that those who are able to work ought to work. This particular focus on work has come at the expense of another, far more radical policy goal, that of creating ‘less work,'” Spencer wrote in his Guardian essay. “Yet…the pursuit of less work could provide a better standard of life, including a better quality of work life.”

And it may also help save us from environmental catastrophe.

GLOBAL TIPPING POINT

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the top research body on the issue recognized by the United Nations, recently released its fifth report summarizing and analyzing the science and policies around climate change, striking a more urgent tone than in previous reports.

On April 13 at a climate conference in Berlin, the panel released a new report noting that greenhouse gas emissions are rising faster than ever and urgent action is needed in the next decade to avert a serious crisis.

“We cannot afford to lose another decade,” Ottmar Edenhofer, a German economist and co-chairman of the committee that wrote the report, told The New York Times. “If we lose another decade, it becomes extremely costly to achieve climate stabilization.”

After the panel released an earlier section of the report on March 31, it wrote in a public statement: “The report concludes that responding to climate change involves making choices about risks in a changing world. The nature of the risks of climate change is increasingly clear, though climate change will also continue to produce surprises.”

The known impacts will be displaced populations in poor countries inundated by rising seas, significant changes to life-supporting ecosystems (such as less precipitation in California and other regions, creating possible fresh water shortages), food shortages from loss of agricultural land, and more extreme weather events.

What we don’t yet know, these “surprises,” could be even scarier because this is such uncharted territory. Never before have human activities had such an impact on the natural world and its delicate balances, such as in how energy circulates through the world’s oceans and what it means to disrupt half of the planet’s surface area.

Researchers have warned that we could be approaching a “global tipping point,” in which the impact of climate change affects other systems in the natural world and threatens to spiral out of control toward another mass extinction. And a new report funded partially by the National Science Foundation and NASA’s Goodard Space Center combines the environmental data with growing inequities in the distribution of wealth to warn that modern society as we know it could collapse.

“The fall of the Roman Empire, and the equally (if not more) advanced Han, Mauryan, and Gupta Empires, as well as so many advanced Mesopotamian Empires, are all testimony to the fact that advanced, sophisticated, complex, and creative civilizations can be both fragile and impermanent,” the report warned.

It cites two critical features that have triggered most major societal collapses in past, both of which are increasingly pervasive problems today: “the stretching of resources due to the strain placed on the ecological carrying capacity”; and “the economic stratification of society into Elites [rich] and Masses (or ‘Commoners’),” which makes it more difficult to deal with problems that arise.

Both of these problems would be addressed by doing less overall work, and distributing the work and the rewards for that work more evenly.

SYSTEMIC PROBLEM

Carol Zabin — research director for the Center for Labor Research and Education at UC Berkeley, who has studied the relation between jobs and climate change — has some doubts about the strategy of addressing global warming by reducing economic output and working less.

“Economic activity which uses energy is not immediately correlated with work hours,” she told us, noting that some labor-saving industrial processes use more energy than human-powered alternatives. And she also said that, “some leisure activities could be consumptive activities that are just as bad or worse than work.”

She does concede that there is a direct connection between energy use and climate change, and that most economic activity uses energy. Zabin also said there was a clear and measurable reduction in greenhouse gas emissions during the Great Recession that began with the 2008 economic crash, when economic growth stalled and unemployment was high.

“When we’re in recessions and output and consumption slow, we see a reduction in impact on the climate,” Zabin said, although she added, “They’re correlated, but they’re not causal.”

Other studies have made direct connections between work and energy use, at least when averaged out across the population, studies that Rosnick cited in his study. “Recent work estimated that a 1 percent increase in annual hours per employee is associated with a 1.5 percent increase in carbon footprint,” it said, citing the 2012 Knight study.

Zabin’s main stumbling block was a political one, rooted in the assumption that American-style capitalism, based on conspicuous consumption, would continue more or less as is. “Politically, reducing economic growth is really, really unviable,” she told us, noting how that would hurt the working class.

But again, doesn’t that just assume that the pain of an economic slowdown couldn’t be more broadly shared, with the rich absorbing more of the impact than they have so far? Can’t we move to an economic system that is more sustainable and more equitable?

“It seems a little utopian when we have a problem we need to address by reducing energy use,” Zabin said before finally taking that next logical step: “If we had socialism and central planning, we could shut the whole thing down a notch.”

Instead, we have capitalism, and she said, “we have a climate problem that is probably not going to be solved anyway.”

So we have capitalism and unchecked global warming, or we can have a more sustainable system and socialism. Hmm, which one should we pick? European leaders have already started opting for the latter option, slowing down their economic output, reducing work hours, and substantially lowering the continent’s carbon footprint.

That brings us back to the basic question set forth in the Rosnick study: As productivity increases, should those gains go to increase the wages of workers or to reduce their hours? From the perspective of global warming, the answer is clearly the latter. But that question is complicated in US these days by the bosses, investors, and corporations keeping the productivity gains for themselves.

“It is worth noting that the pursuit of reduced work hours as a policy alternative would be much more difficult in an economy where inequality is high and/or growing. In the United States, for example, just under two-thirds of all income gains from 1973-2007 went to the top 1 percent of households. In that type of economy, the majority of workers would have to take an absolute reduction in their living standards in order to work less. The analysis of this paper assumes that the gains from productivity growth will be more broadly shared in the future, as they have been in the past,” the study concludes.

So it appears we have some work to do, and that starts with making a connection between Earth Day and May Day.

EARTH DAY TO MAY DAY

The Global Climate Convergence (www.globalclimateconvergence.org) grew out of a Jan. 18 conference in Chicago that brought together a variety of progressive, environmental, and social justice groups to work together on combating climate change. They’re planning “10 days to change course,” a burst of political organizing and activism between Earth Day and May Day, highlighting the connection between empowering workers and saving the planet.

“It provides coordinated action and collaboration across fronts of struggle and national borders to harness the transformative power we already possess as a thousand separate movements. These grassroots justice movements are sweeping the globe, rising up against the global assault on our shared economy, ecology, peace and democracy. The accelerating climate disaster, which threatens to unravel civilization as soon as 2050, intensifies all of these struggles and creates new urgency for collaboration and unified action. Earth Day to May Day 2014 (April 22 — May 1) will be the first in a series of expanding annual actions,” the group announced.

San Mateo resident Ragina Johnson, who is coordinating events in the Bay Area, told us May Day, the international workers’ rights holiday, grew out of the struggle for the eight-hour workday in the United States, so it’s appropriate to use the occasion to call for society to slow down and balance the demands of capital with the needs of the people and the planet.

“What we’re seeing now is an enormous opportunity to link up these movements,” she told us. “It has really put us on the forefront of building a new progressive left in this country that takes on these issues.”

In San Francisco, she said the tech industry is a ripe target for activism.

“Technology has many employees working 60 hours a week, and what is the technology going to? It’s going to bottom line profits instead of reducing people’s work hours,” she said.

That’s something the researchers have found as well.

“Right now, the problem is workers aren’t getting any of those productivity gains, it’s all going to capital,” Schor told us. “People don’t see the connection between the maldistribution of hours and high unemployment.”

She said the solution should involve “policies that make it easier to work shorter hours and still meet people’s basic needs, and health insurance reform is one of those.”

Yet even the suggestion that reducing work hours might be a worthy societal goal makes the head of conservatives explode. When the San Francisco Chronicle published an article about how “working a bit less” could help many people qualify for healthcare subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (“Lower 2014 income can net huge health care subsidy,” 10/12/13), the right-wing blogosphere went nuts decrying what one site called the “toxic essence of the welfare state.”

Chronicle columnist Debra Saunders parroted the criticism in her Feb. 7 column. “The CBO had determined that ‘workers will choose to supply less labor — given the new taxes and other incentives they will face and the financial benefits some will receive.’ To many Democrats, apparently, that’s all good,” she wrote of Congressional Budget Office predictions that Obamacare could help reduce hours worked.

Not too many Democratic politicians have embraced the idea of working less, but maybe they should if we’re really going to attack climate change and other environmental challenges. Capitalism has given us great abundance, more than we need and more than we can safely sustain, so let’s talk about slowing things down.

“There’s a huge amount of work going on in society that nobody wants to do and nobody should do,” Carlsson said, imagining a world where economic desperation didn’t dictate the work we do. “Most of us would be free to do what we want to do, and most of us would do useful things.”

And what about those who would choose idleness and sloth? So what? At this point, Mother Earth would happily trade her legions of crazed workaholics for a healthy population of slackers, those content to work and consume less.

Maybe someday we’ll even look back and wonder why we ever considered greed and overwork to be virtues, rather than valuing a more healthy balance between our jobs and our personal lives, our bosses and our families, ourselves and the natural world that sustains us.