marke@sfbg.com

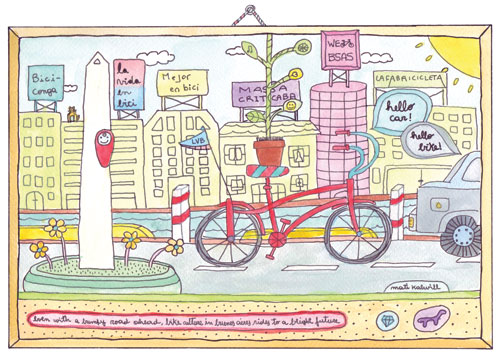

TRAVEL TALES Earlier this year, a wave of revolution swept the Arab world: Tunisia and Egypt deposed their dictators through popular protest, almost all of it nonviolent and nonsectarian, with similar uprisings — many still in progress — in pretty much every other country with a substantial Arab population. Democracy was the stated goal of many of these upheavals, and a newly technologized pan-Arab youth movement was leading the way to freedom via Facebook and Twitter, using social networking to undermine long-entrenched authoritarianism.

It was inspiring. It was exhilarating. It was absolutely delicious.

Pastry vendor, Marrakech. All photos by David Schnur

Hunky Beau and I wanted to taste the revolution. We planned a trip to check out Morocco — which, despite the nonviolent, populist Fevrier 20 movement, had so far escaped turmoil due to a popular and quick-footed king — and Tunisia, which was still dazed by its quick success and which we wanted to support with our meager tourist dollars and a show of good will. The outbreak of air bombing in Libya stymied any plans to expand our journey to Egypt, so we made do with more time in our Spanish travel base, Madrid, which underwent its own plaza-occupying convulsions while we were there, influenced by the Arab Spring.

Berber castle, Southern Morocco

Besides the energy, though, we sought the flavors. The scintillating temptation of Maghreb (North African) cuisine, a hybrid of zesty Mediterranean, formal French, savory Arabic, Spice Route African, and indigenous Berber flavors, was possibly a mirage in this globalized world of ours, but it seemed one worth chasing, preferably by camel, even if it came served on a pizza with a side of fries. Also I wanted to explore my Arab heritage a bit — I’m half-Lebanese, but as pretty much everyone we met in North Africa observed, I have “Berber face.” I’d eat my way to my roots!

Central roundabout, Douz, Tunisia

So off we headed in April and May, a newly gay-married, half-Arab virtual drag queen nightlife columnist and a punk-rock Jewish leather enthusiast, backpacks laden, travel sporks at the ready.

PIGEON PIE AND PISTACHIO JUICE

Fez, my friends, is magical chaos. You will hardly get a minute alone. The life of the justly famed souk (market) dominates this pale, sprawling adobe metropolis. You are here to buy things, and the citizens are going to use any means necessary to sell things to you. The labyrinthine souk itself befuddles and enchants: an ancient, arterial maze of sensory overload, jostling with polyglot shoppers, hard-haggling hawkers, dogged hustlers, shrieking children, braying mules, the odd scrawny chicken. No one wears fezzes. Intertwined roof slats suffuse the tiny passageways with idyllic light. Food stalls tower with rose hips, fig relish, lamb heads, preserved lemons, mint leaves for the ever-present national drink (syrup-sweet mint tea), and myriad pyramids of neon-tinted spices.

And always someone wanting to meet you, someone wanting to know where you’re from. “Ali Baba!” some would call me, referring to my beard. “Obama!” many would say admiringly, shining with African pride, on learning we were rare American visitors. And then, ugh, “Schwarzenegger!” when we mentioned California.

In the Fez souk

Morocco doesn’t have a native dining-out tradition, people eat big meals at home, so we had to hit up tourist restaurants for basic dishes like steaming heaps of vegetable couscous; bubbling, cumin-spiked lamb tajine; and the fabled kefta mkaouara, beef meatballs stewed with eggs and paprika. That was fine, these were good and everywhere. Street food was our real holy grail. Hunky Beau was observing Passover in the Sephardic kosher tradition, which meant avoiding most doughs, so he munched on a array of meaty kabobs. Moroccans will skewer and roast almost anything. Meanwhile, I went all in for a Fez specialty, bastilla (pigeon pie), snagged from a jolly vendor near the ATM at the Bab Boujeloud gate. The small, addictive, golden-baked phyllo triangles stuffed with squab, cinnamon, almonds, salt, and sugar steamed with savory sweetness. I ate, like, 10.

When the pandemonium became too much, we clung to thick, musky camel burgers on the roof of Cafe Clock, located in a medieval water clock tower; drank fortifying bowls of tomato lentil harira soup from the nice guy next to the garish Cremerie Disney Channel ice cream parlor; or rested in Place Baghdadi, a huge square surrounded by the old city’s crenellated walls, where the city’s mass of unemployed young men gathered in the evening to socialize and dig through a massive clothing swap. There we sipped tart glasses of radioactively chartreuse pistachio juice, purchased from a cart run by Fatal Tigers, the boisterous fan club of Fez’s champion soccer team, and discussed world affairs with the city’s male youth. (Morocco was packed with lively women who, apparently, were busy doing everything. We did eventually make a few female friends. however.)

A rare woman in Place Baghdadi

By the way, did I mention that young Arab people — and 65 percent of the Arab world is under 30 — are freaking gorgeous? Seriously, we’re about to see some major Arab children flooding our runways. But most of them are dressed in G-Star Raw knockoffs, which I guess is like Old Navy now in Europe? And who knew that those cute boys whispering “shooky” weren’t offering us hash at all, but blow jobs? Oh well.

Older Moroccan men gathered in the evening to play the backgammon-like shesh besh and talk politics at sidewalk cafes, like Salon de Thé Afaf, where we joined them for espresso with a side of water (cafe noir avec l’eau) a Fez staple, and nibbled on roasted chickpeas sprinkled with cumin, watching the hurly-burly street scene and Al Jazeera simultaneously in the fading pink light. No matter what was happening in other Arab countries — like satellite dishes and vehicular hubbub, Al Jazeera’s breathless revolution reporting was everywhere — young King Mohammed VI had so far managed to dodge the boot by immediately offering, and later following through on, constitutional reforms. Compared to everywhere else, this country of 32 million was almost too peaceful. Or so it seemed.

A BOWL OF SNAILS

It smelled like the sewers had been backing up all week by the time we entered Marrakech, so a gas explosion didn’t seem so entirely out of the question. We’d just come from the “Hollywood of Africa,” Ouarzazate, where Lawrence of Arabia and Gladiator were filmed. A fantastically diverse former caravan trade route outpost, Ouarzazate lay on the edge of the Sahara and was the gateway to the Draa Valley, studded with crumbling Berber warrior ksars (fortresses) from long ago. While there, we happened upon an enormous International Women’s Day celebration, bursting with brightly attired clans, ululations abounding. It was some fierce female power out there.

International Women’s Day, Ouarzazate, Morocco

And we had to check out one of North Africa’s top French-Berber restaurants, Relais Saint-Exupéry — named for The Little Prince author and storied desert aviator’s private runway — where, for about $30 we could pull out the stops with an eight-course formal diner Francais. Lapin and canard pate, balled melon pelted with pink peppercorns, a tangy, deep-red dromedaire avec sauce “Mali,” and a tiny chalice of Berber fig liquor were soon finished off, as was a yummy bottle of full-bodied 2002 Domaine du Sahari Guerrouane Rouge. That’s right, even in the Sahara I could sniff out wine.

In the Draa Valley

Les Jeunes Tinariwen de M’Habib performing in Ouarzazate

Now, unearthly, overcast, red-walled Marrakech thrummed with activity, masses of tourists pouring into the huge, famous Djemaa El Fna square. Djemaa is basically where all your Raiders of the Lost Ark fantasies of Morocco come to life — snake charmers, smoke-pouring food stalls, boisterous storytellers, scheming monkeys, even (yes!) elaborate drag shows. Except, of course, for all the cell phones, dreadlocked Spanish kids in genie pants, and tacky French families dressed in the worst cheap Quechua brand travel wear imaginable. Obviously, colonialism didn’t win.

The morning of April 28 we’d hunted in vain for bisara, a thick pea breakfast soup drizzled with green olive oil from Moulay Idriss, but had given up, grabbed a couple kaab el ghzal (“gazelle’s horns,” small croissants stuffed with almond paste) and decided to e-mail our folks.

We were in a nearby Internet cafe when the blast hit. The clock rocked against the wall: 10:56. A man in a hooded shepherd’s tunic at the terminal next door looked up at me, panicked, and then mimed ducking under his desk as a question. I wasn’t sure how to answer. When no immediate second blast came, we hurried out of the building. No source of the explosion could be found, but Hunky Beau and I both had the same thought: the square. We walked about 100 meters and rounded the corner into catastrophe.

It looked like the Cafe Argana, a large, terraced tourist favorite, where backpackers regularly stopped for ice cream sundaes, had folded in on itself. A man dressed in a tuxedo gestured like a mad maitre d’ from the collapsing second floor to the crowd below, most of which was covered with debris. We surged forward to see what we could do, but people were already hauling off bodies. I saw a frantically shaking, middle-aged white woman lifted in the air with no legs. A man’s bald head lay on a table, an arm (his?) had landed like a limp bird on a crumpled metal railing. Yellow tablecloths were used as stretchers, as shrouds. Finally, the ambulances came.

Stunned, we walked slowly from the square. Morocco was supposed to be safe! Rumors quickly spread. Someone was smoking by a gas canister. An oven had exploded. An old furnace burst. Polisario, the Western Saharan separatist group, had struck. The anti-monarchical Fevrier 20 movement had turned violent. Possibly Al Qaeda itself?

It kind of was. In the end, 17 people died, Moroccans as well as foreigners, including a 10-year-old girl. A man in his 20s named Adel Othmani is accused of dressing “like a Western hippie” with long hair and a guitar case, ordering an orange juice, and leaving behind a bomb that he later detonated with a cell phone. (The Fevrier 20 movement led a peace vigil the night of the bombings, at which people symbolically drank glasses of orange juice to protest terrorism.) Al Qaeda in the Western Maghreb officially denied involvement — though it supported the outcome — but it seems Othmani was a terrorism junkie, trying previously to get into Iraq and Chechnya, and the government claims that he bombed the Argana as a tribute to Al Qaeda. This was like his audition! What psychological madness can grip our world’s young. I had never been so close to pure evil.

The people of Marrakech are nothing if not resilient, though. A day later and it was almost as if nothing happened. Out came the snake charmers, out came the Quechua Frenchmen. (Al Qaeda is tired, anyway — the Arab Spring is mostly about the economy and internal reform, not religious war and anti-Westernism.) All the tourist restaurants and food stalls were closed in the square though. Since we were still in shock and hardly had any appetite, we took the opportunity to order some of the more adventurous things on offer in the market. A bowl of snails ladled by a handsome vendor held a surprisingly delicious broth (soup will always help) and the snails, extracted with a toothpick, were more chewy than slimy, like salty jerky.

And a shared ground beef heart sandwich, richer than anything, washed down with an avocado shake, even richer than that, helped calm our stomachs. Our thoughts, however, remained disquieted.

TUNA TUNISIENNE

OK, food. “Thank you Facebook” read graffiti in English on Avenue Bourguiba, Tunis’ main thoroughfare. “The women of Tunisia are and will remain free” read another in French. And another in Arabic: “Bourguiba is for the people,” referring to either the road itself or the beloved Westernizing dictator it was named after, who ruled before the dictator the people just kicked out.

Tunisia is regarded as the most educated country in North Africa — a program of free schooling proved deposed authoritarian Ben Ali’s undoing when students, frustrated by the lack of jobs, used their knowledge to organize and overthrow him. (We met a street hustler named Wassam, for example, who said he held degrees in art history, math, and textile design, because what else had there been for him to do except keep enrolling in school?) So if we felt intimidated that everyone in Morocco was expected to speak at least three languages fluently — French, Standad Arabic, and Moroccan Arabic — here was a whole country of people who could probably help build a superconductor.

Five months after the revolution, however, and the recession was still there. General disgruntlement was simmering again. Protesters, impatient for the July general elections (later postponed until October) were showing up on the ministry steps. The shine of the revolution appeared to be tarnishing. Still, everyone we met was so intensely proud of what they’d accomplished, positively giddy with their newfound freedom of speech. We had no problem making conversation. Any lingering bitterness about the Bush era seems to have been dispelled once President Obama signed on to NATO’s bombing campaign against Gadaffi. They hate Gadaffi.

Because of the recent clashes between protesters and police, however, the interim government had imposed a 9 p.m. curfew right when we arrived. That made it difficult to find dinner — northern Tunisians are European in their late eating habits — but everyone seemed to take it in stride. Cafes were bustling on the evening sidewalks beneath Tunis’ famous mid-20th-century architectural gems.

Plates came laden with Tunisian staples: creamy mechouia (eggplant salad), bread and dipping harissa (hot red pepper paste), young olives, salade Tunisienne (shredded tuna with olive oil and tomatoes), and slata (mixed salad). Our dinner experience — with alcohol! — at seafood paradise L’Orient included octopus steaks simmered in cumin sauce and a dazzling platter of fruits de mer. (Tunisia has 700 miles of glittering Mediterranean coastline, a seafood lover’s paradise.) A row of restaurants serving cuisine from the southern city of Sfax hooked us on salt-and-pepper fried fish over couscous and stewed rabbit with pequillo peppers. And, believe it or not, Tunisian sandwiches, stuffed with tuna, olives, harissa, and french fries, are bangin’.

A certain wide-eyed tension between the past and future could be felt everywhere in the white and turquoise city. Cell phone ads targeting gay men, however ambiguously, had started showing up, and gay groups were emerging from the shadows with blogs and Facebook pages. At the same time, some religious women were reembracing the head-covering hijab, banned since 1981. Hip-hop had fueled the revolution — the aggressive sounds of El General, DJ Costa, and Blid Boy blared next to those of classic divas like Fakhet Amina and Oum Kalthoum and more traditional raï singers. (And then there were the ethereally overamplified calls to prayer from the muezzins high atop their minarets, some of them divas in their own right, auditioning for Arabian Idol. You’ve never heard the Koran recited until you’ve heard it AutoTuned.)

Finally, there’s the Carthaginian connection, with breathtaking mosaics and legendary landmarks from the classical empire that rivaled Rome scattered everywhere. We could barely tear ourselves away from the great archaeological treasures of the Bardo Museum, located in an old harem, but we were eager to make our way to the south, where the revolution began, and where we heard the ojja (sausage stew) was piping hot.

More tasty camels, another brush with Al Qaeda, and an Englishwoman who said God told her to drive through Libya with a Jesus fish on her bumper: Read part two of this story here.