arts@sfbg.com

SFJFF Given the seemingly endless one-step-forward, two-steps-back nature of peace negotiations in the Middle East, it seems a fair bet that the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival (July 24-Aug. 10) will never stop being among the most politically charged among umpteen annual Bay Area film festivals. But considerably older than the state of Israel — and all attendant controversies — is an aspect of Jewish history that reliably provides a counterbalance to the inevitable heavyweight documentaries and dramas. That would be the ubiquity of Jewish talent in popular entertainment, as performers, presenters, and in every other necessary role.

An old saw that never exactly went away but nonetheless has come back with a vengeance in our alleged post-racial era is that perpetual complaint of the envious, paranoid, and prejudiced that “the Jews run Hollywood.” While it’s true that the movie biz has always has employed a large number of Jewish people, anti-Semites have only themselves to blame for originating this state of affairs. It was the entertainment industry’s lack of respectability in its fledgling years that created an opening for an industrious and imaginative minority who were frequently discouraged from sullying more prestigious art forms with their participation. For decades (arguably even now) many stars, studio moguls, and others tried to downplay or entirely hide their ethnic identity; the silent era, in particular, was a hotbed of biographical revisionism among Hollywood players. Nonetheless, Jewish business, tech, design, and acting talents established deep roots in moviemaking well before Hollywood as idea or physical entity existed, precisely because flickers were initially viewed as a lowbrow novelty unfit for the higher working castes. A very sad microcosm of that semi-hidden Jewish industry presence’s early heights and depths is offered offered by David Cairns and Paul Duane’s multinational documentary Natan, about a hugely important yet lamentably overlooked figure in French cinema. Romanian-born Bernard Natan went from projectionist to cinematographer, producer, film laboratory owner, and more in the medium’s early days. An innovator in the use of sound, color, wide screen, and other techniques, he helped rebuild French film production whole in the aftermath of World War I (in which he volunteered for military service, despite not yet being a legal French citizen).

His extraordinary, tireless enterprise made him an ideal candidate to take over pioneering and powerful, but financially teetering, Pathé Studios in 1929. He virtually rescued it from ruin, while steering it successfully into the talkie era. But despite his efforts, Pathé went bankrupt at the height of the Depression in 1935. Natan was the designated fall guy because he’d used legally questionable means in an attempt to cover losses created largely by people and institutions outside his control. There was a strong whiff of then-increasingly-fashionable anti-Semitism to his pillory: He was accused not only of fraud, but of hiding his Jewish heritage, and of being a pornographer.

The latter charge was accepted with remarkable gullibility by historians until quite recently. But as this doc suggests, painting Natan as a predatory perv making potentially career-ending stag reels makes as little sense realistically as it makes great sense propagandically. (We also see how vague the resemblance is between him and the dude or dudes in “smokers” he’d said to have performed in.) That taint helped usher him to prison in Nazi-occupied France, then to an unrecorded demise at Auschwitz. Shamefully, as late as 1948 his estate was still being sued by an invigorated Pathé. Natan is a belated reclamation of a forgotten cultural giant’s abused reputation.

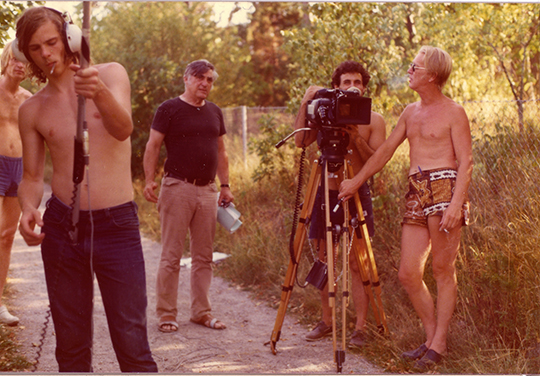

Whether or not he ever actually had anything to do with filmed erotica, Natan would have been amazed by the career of another cosmopolitan Jew launched just a few years after his life’s end. Wiktor Ericsson’s A Life in Dirty Movies pays bemused biographical homage to what Annie Sprinkle calls “the Ingmar Bergman of porn.” Joe Sarno’s micro-budgeted features targeting “the raincoat crowd” from 1962 onward were exceptionally moody, complex and tortured psychodramas focused on being “as hot as you could without showing anything.” He met his soul mate in aspiring off-off-Broadway actress Peggy, who “could discuss John Ford and Truffaut and Renoir” while juggling all the logistical and fiscal details he was naturally oblivious to as a genu-wine artist.

It’s hard now to imagine the mixed excitement and bewilderment that must have been experienced by 42nd Street grindhouse patrons as they witnessed the likes of 1962’s horrors-of-swingerdom melodrama Sin in the Suburbs, or 1967’s claustrophobic self-portrait-of-a-neurotic-artist All the Sins of Sodom. Strangely not glimpsed in this documentary is the artistic apex of Sarno’s color softcore career, 1972’s Pirandello-esque Young Playthings.

The marketplace soon muscled him into hardcore. He was unhappy enough chronicling graphic XXX action to seriously risk financial ruin — and Peggy, still very much the histrionic type, is seen here swanning about as protector of his legacy. It’s lovely when his unexpectedly big 2010 New York Times obit affirms at last to her that he’s “famous like everybody else,” just as he’d always hoped, and as her scandalized Establishment parents figured he’d never be.

Other features in this year’s SFJFF area focus less on impresarios than on performers. The festival’s Freedom of Expression Award goes to the subject of Theodore Bikel: In the Shoes of Sholem Aleichem. This is one of those occasional, simultaneously valuable and dubious documentaries that enlarge upon a well-traveled celebrity solo stage showcase (Sholem Aleichem: Laughter Through Tears). The 90-year-old Bikel has done Aleichem’s characters (especially Tevye the Dairyman) so much that the excerpts here feel worn into a groove that congratulates both veteran performer and veteran viewers who recognize bits they’ve already seen. Who can object? He’s like a tabby grooming itself, essential adorability undeniable.

But he never allows himself an unrehearsed moment in what comes off first as an awfully self-congratulatory self-portrait, and secondly as a workmanlike salute to the single greatest shaper of all American Jewish cultural tropes. Shoes is the kind of proud, way-back machine tribute that makes you feel like you’re watching its 12th pledge week replay. Why are the likes of Gilbert Gottfried and Dr. Ruth the principal interviewees here? Because everybody else has moved on, maybe. Aleichem will always be classic, but to what extent do contemporary US Jews recognize themselves in his worldview?

Other entertainers showcased in SFJFF 2014 include The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Psychic Spy?, about the Tel Aviv-born “spoonbender” phenomenon. This UK documentary assumes a campy, skeptical stance re: his paranormal fame, while actually providing evidence that he’s far from a fraud. Go figure. An even more swinging figure of the era is the subject of Quality Balls: The David Steinberg Story. The dapper latter epitomized smart, improv-based standup comedy on a national stage once he’d left Chicago’s Second City for TV — surviving the 1969 cancellation his edgily political material purportedly forced upon the hugely popular The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. Those looking for an additional peek behind the comedic curtain might also check out documentary feature Comedy Warriors, about disabled Iraq and Afghanistan veterans taking the standup stage; Little Horribles: An Evening With Amy York Rubin, drawn from the popular online series; and thematic program “Jews in Shorts.”

Then there’s this year’s major excavation from the treasure-trove of forgotten US Yiddish cinema: 1938’s Mamele, in which late pixie queen Molly Picon plays a cheerfully suffering yenta Cinderella awaiting justice for her many sacrifices to a selfish family. She cooks, she cleans, she sings — what more do you want? Of course there’s a happy ending. 2

SAN FRANCISCO JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL

July 24-Aug. 10, most shows $10-$14

Various Bay Area venues