marke@sfbg.com

DEATH ISSUE The first one I land on, incredibly, is Paul Lynde. The lisping, bescarved Hollywood Squares comedian didn’t die of AIDS (heart attack, supposedly). But it was 1982, and rumors on the gay underground flew. Also, everybody was panicking. The obituaries editor at the Bay Area Reporter evidently thought a little cheering up was in order. So under the heading “Gay Favorite Paul Lynde Dies,” several of his signature risque quips are listed. Q: What’s the largest use of leather in this country? A: Party favors. Q: Is there any state in the Union where flogging is still used as a punishment? A: Oh God, I hope so!

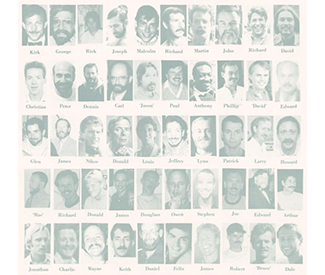

A good laugh at a bad joke seems an inappropriate way to dive into the B.A.R. and the GLBT Historical Society’s great Online Searchable Obituary Database (obit.glbthistory.org). The database, launched on World AIDS Day, December 1 in 2009, by valiant volunteer Tom Burtch, archives scans of every obituary that’s appeared in the gay-serving newspaper roughly since 1980, which means the crux of the AIDS years. But if you hit the “view random obituary” button enough times — the faces, names, dates, stories, details, tributes touching or angry or awkward or all three whizzing past — you get a glimpse of the horrible cosmic joke that was AIDS, and the vibrant, heroic riposte that was the power of the local community in the face of almost 20,000 deaths. (The database contains thousands of obituaries. Don’t read them all at once.)

In those early years of the epidemic — I miraculously survived them — obituaries were the gay news. Outside of intimate friendships or gossipy bar-talk, there was no other way to learn the actual, true-life stories of other gay people: no shrugged-at gay storylines on reality TV or coming out applause on talk shows and gossip sites, no oversharing on Facebook, no breathless same-sex wedding announcements in the Times detailing the power-brides’ family lineage and corporate achievement. Back then we could barely shoehorn a drag queen into a sitcom.

It was often only in the brief paragraphs (and between the lines) marking a death that you learned life-defining, deeply human personal details about people around you, like you: this one trained as a classical oboist in Tallahassee, that one came from a long line of car mechanics, this one had three children in Hayward, that one broke up with his lover of 24 years right before he passed. Whose family stuck with them as they withered away. Who just ended it themselves. What medications may not be working anymore. What new disease to be afraid you would contract, too. Who might not have had any friends left to write more than the shortest sentence about their life.

Even though the obits archive also includes people who didn’t die of AIDS, it’s a glowing repository of the San Francisco gay-and-friends community’s stories, encompassing an age range from 19 to 95, from all walks of life. And, oh, what stories! Doris “Dori” Jennings, in her signature oversized glasses, ran Club Dori, the longest-running gay bar on Presidio, and dressed as a nurse every New Year’s Day to “help mend hangovers and break resolutions.” “A rave-head to the end,” Ralph McGee “was wildly gyrating, shiny black with sweat, at Come-Unity days before he died.” Albert Lee Little was survived by “master Bill, daddies Scott and Cliff, wife Starrly, sons Cale and Michael, and daughters Griffin and Sabine.”

Jay Freezer invented poppers. Jerry Jacks started the first gay and lesbian science fiction fan club, the Urania Society. Colin David Groom was Sister Unity-Harmony of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. Jack Caster, who managed the AIDS Quilt tour, “loved opera and couldn’t carry a tune.” George “Gigi” Hanson “blew that one-horse town” of Idaho Falls. “Big Mama” McGowan has “taken his place at God’s right hand.” Adrien Keel died just before the 49ers game, wishing they would win — and they did.

Back when you could move here with only a backpack and a cute smile and make a new life for yourself, however short, the city was full of such characters. Of course it still is, if you look. And despite the waning of AIDS (it’s still with us!) I think many gay men still approach each others’ death with the same voracious curiosity about the details of their lives. The minute we hear from a friend of a friend’s feed about someone dying — especially in this time of skyrocketing LGBT suicide rates — we race to their Facebook page to glean what details we can. And if that person’s wall is set to public, we watch a dizzying, digital monument erected before our very eyes by a mish-mash of people from the deceased’s various stages of life. In the end, though, those monuments always look so similar, bristling islands of anguished and loving posts floating forever in cyberspace — just as final emails from loved ones linger like talking ghosts in our saved folders.

“What if there’d been Facebook during AIDS?” I’ve often wondered. Tom Burtch has said that he hopes his monumental project grows to become more interactive, where friends could upload photos and memories, “like a Facebook page for each person.”

But then, in the archive, you might hit upon an obituary written by the deceased himself, that tells you all you really need to know. Donald Boyd, born 1956, died 2006 of AIDS-related cancer: “This picture was taken about 10 years ago, when I was at my happiest, in the summer, in the sun, naked, by the water, with very good friends. I had a lot of good in my life, but I also had my share of bad. I look forward to eternal peace or even better, a reunion with lost friends and family.”

Maybe, in the end, the best stories are the ones we tell about ourselves.