cheryl@sfbg.com

FILM With Django Unchained-related posts currently filling up your Facebook feed (and box-office receipts stuffing Quentin Tarantino’s pockets), now seems the perfect time to amble over to Berkeley for the Pacific Film Archive’s spaghetti western series.

Six-part “The Hills Run Red: Italian Westerns, Leone, and Beyond” highlights some of the genre’s most notable B-sides, with three examples of ‘ghetti subset “Zapata westerns,” plus a Monte Hellman oddity, a leather-clad display of youthful Burt Reynolds charisma, and a Lee Van Cleef classic. Expect multiple train heists and shootouts, dubbing that runs the gamut from questionable to surreal, class warfare, much macho chest-beating, and some stellar Ennio Morricone ear candy — including scores sampled by Tarantino over the years. Do not expect any political correctness whatsoever.

Plot incoherence and generous helpings of cheese are also on the menu in 1971’s Duck, You Sucker!, also known as A Fistful of Dynamite. Director Sergio Leone took the gig reluctantly; he’d wanted a break from westerns after 1968’s Once Upon a Time in the West, but came aboard after Peter Bogdanovich, Sam Peckinpah, and Giancarlo Santi (Leone’s assistant on West and 1966’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) jumped ship for reasons both personal and producer-mandated. The casting of leads James Coburn (as an Irish explosives expert) and Rod Steiger (as, uh, a Mexican bandit) also came after a round-robin of choices were bandied about — including George Lazenby, fresh off his first and last James Bond portrayal, for Coburn’s part.

At any rate, Duck opens with a Mao quote that reminds us “The revolution is an act of violence.” We meet Juan (Steiger, whose accent foreshadows Scarface by 12 years) peeing on an anthill and weaseling his way onto a stagecoach populated by snobby gringos. After an uncomfortably extended sequence comprised of extreme close-ups of richie-rich lips and teeth — chomping food, hurling insults at the peasant in their midst — Juan reveals he’s actually a serial robber, helped along by his extended brood of scrappy sons. Sure, there’s a revolution going on, but he’s in it for personal gain. “My country is not my family,” he mutters later in the film; revolutions, he says, are planned by men who read too many books — and carried out by poor people, many of whom don’t live to see the end result.

This observation proves eye-opening for Mallory (Coburn), who gives his first name as John, though his true name is Sean — which, to my ears, is one of the recurrent motifs in Morricone’s score (“Shon! Shon!”) On the run from his IRA misdeeds — shared throughout the film in superfluous, soft-focus, slo-mo flashbacks — the dynamite addict joins Juan’s crew to help rob a bank, or so Juan thinks, until he realizes the Irishman has neglected to mention that the vault contains political prisoners, not gold. Having sprung hundreds of captives purely by accident, Juan becomes the world’s most reluctant revolutionary hero. Meanwhile John/Sean works through his own demons by applying generous amounts of TNT to bridges, trains, etc.

Shorter than Django by 20 minutes or so, Duck is still overlong, with a tone that careens from fist-raising earnestness to kitschy over-the-topness. The latter is only enhanced by the performances — Steiger’s, mostly, though Coburn isn’t immune, and neither is the hollow-cheeked actor who plays the duo’s army nemesis; who knew brushing one’s teeth could look so … evil? Duck may be an imperfect movie — particularly in the context of Leone’s slender yet masterly filmography — but it has the Zapata western format down pat, with its dual heroes (typically, one’s a simple Mexican capable of unexpected heroics; one’s a European or American whose refined dandiness belies his secret propensity for bad-assery), dusty period setting, and political themes. It’s predated by two structurally similar films included in “The Hills Run Red”: Sergio Corbucci’s The Mercenary (1968) and Damiano Damiani’s A Bullet for the General (1966).

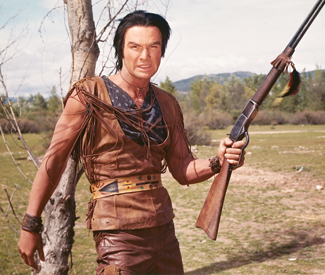

Corbucci’s Navajo Joe (1966) also plays the PFA series; it’s a more conventional tale of a rogue Native American who brings hope to a crook-plagued frontier town, distinguished mostly by hot-young-thang Reynolds and a screamy, tom-tom-y score by one “Leo Nichols” (a.k.a. Morricone). But The Mercenary is the film to see if you’ve gotta choose. You’ll still get your Morricone, whistle-heavy as ever, but you will also get Franco “the original Django” Nero playing gunslinger Sergei “the Polack” Kowalski, opposite Tony Musante (giallo fans will recognize him from Dario Argento’s 1970 debut, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage) as loopy rabble-rouser Paco. Plus: Jack Palance as demented heavy “Curly,” a character that hardly resembles the Curly he’d win an Oscar for playing in 1991’s City Slickers.

The Mercenary is nuts, in a good way. Within the first five minutes, there are rodeo clowns, the sight of Kowalski forcing a cheatin’ gambler to swallow his own weighted dice (in a glass of milk), and Paco cackling through the only-in-westerns punishment of being buried up to one’s neck in a spot frequented by thundering hooves. The unflappable gringo — prone to striking matches on whatever’s convenient: a hooker’s cleavage, a dead guy’s dangling feet — agrees to help train Paco’s ragtag rebels, though Paco doesn’t take direction well, and Kowalski is a bit of a douche. Meanwhile, Curly lurks, seeking revenge on both men, lending his BAMF skills to the Mexican army, and rocking a jaunty carnation in his lapel. (If this all sounds a bit similar to Corbucci’s 1970 Compañeros — well, it is. Except Palance doesn’t smoke weed or own a hand-pecking hawk in this one.)

Even more unhinged is A Bullet for the General, a.k.a. El chuncho, quién sabe?, (score by Luis Bacalov, supervised by Morricone), which gives away its endgame in the title and kicks off with a rapid-fire voiceover offering some historical context: “From 1910-1920 Mexico was torn by internal strife … scenes of this kind were commonplace.” (“Scenes of this kind” being an army firing squad mowing down common folk, natch.) Prim American Bill Tate (Lou Castel) is visiting Mexico in the service of a shadowy plan, which first involves helping a gang of gun-stealing rebels, led by El Chuncho (frequent Leone star Gian-Maria Volonté), rob the train he’s riding. Chuncho can’t figure him out, either, but he’s won over quickly, deducing “You are a smart young gringo!” and dubbing him “El Niño.”

The plot proceeds apace, with the duo pursing the ultimate prize, a machine gun (“more beautiful than any woman!”), but Bullet has one golden ticket that none of the other “Hills Run Red” films can boast of: wild-eyed Klaus Kinski, a frequent spaghetti-er who plays Chuncho’s half-brother. “That man is a lunatic!” a bystander observes. Yep. There are interpretations of Bullet that suggest the film addresses current events of the time (Vietnam; the CIA’s influence in Uruguay, Chile, Bolivia, and other parts of Latin America), but anytime Kinski is onscreen, forget about any subtext. Or subtlety.

The other films in the series don’t fit into the Zapata mold; Gianfranco Parolini’s Sabata (1969) most resembles Navajo Joe in its tale of a drifter whose appearance in dusty Daugherty City, Texas means trouble for the local criminal element, though he’s not exactly law-abiding himself. Star Lee Van Cleef — “the man with the gunsight eyes” — lives up to his nickname here, brandishing some creatively souped-up weapons as he takes on the fey local land baron, who dwells in a hilariously over-decorated manse complete with duelling chamber. Other town residents include an “Indian” whose acrobatic skills are as random as they are impressive (seriously, though, get that guy off the rooftop); a sloppy-drunk Civil War vet who Sabata takes pity on; and “Banjo,” whose instrument fires off both musical notes and bullets. All this, plus lines like, “When I stop laughing, you’re dead!” Essential viewing for Van Cleef fans — was there ever a cooler cat in all of the west?

The offbeat sixth film in the series is Monte Hellman’s 1978 China 9, Liberty 37, neither his first western nor his first film to star Peckinpah favorite Warren Oates. If 1971’s Two-Lane Backtop remains the best-known collaboration between the two, China 9 is worth a look just for its dreamy, melancholy mood. It’s kind of the least-garish, “and Beyond” part of the PFA program, mercifully light on the racist characterizations of Mexicans that make other spaghettis so problematic.

China 9 was an Italian-Spanish production, which accounts for the casting of Italian heartthrob Fabio Testi. He plays Drumm, a quick-draw king who’s granted a last-minute pardon when he agrees to off Sebanek (Oates), a stubborn old cuss who refuses to sell his farm to the railroad. (When the railroad’s on its way in, you know any romantic notion of a wild, wild west is on its way out.) But it gets complicated: Drumm actually likes Sebanek, and he really likes his much-younger wife, Catherine (Jenny Agutter, two years past Logan’s Run, introduced while bathing in a river). When Drumm and Catherine run off together, a left-for-dead Sebanek gives chase.

Because it’s the 1970s, there’s a circus scene (and an end-credits twanger by Ronee Blakley). Everyone’s angry, but everyone’s kinda sorry about it, too, and the movie rambles its way to an uneasy, downbeat conclusion. The hills, however, run red as ever.

THE HILLS RUN RED: ITALIAN WESTERNS, LEONE, AND BEYOND

Jan. 10-27, $5.50-9.50

Pacific Film Archive

2575 Bancroft, Berk.

bampfa.berkeley.edu