arts@sfbg.com

FILM In 1987, Soviet critics were polled to create a list of the nation’s greatest films. Landing on top was a movie still little-known abroad, whose maker has completed just five features in 45 years — one of which he doesn’t even consider truly his own work.

My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1984) likely wouldn’t have gotten near that exalted status if original, party-line-towing critics had had their way. After its well-received first screening, Aleksei Guerman’s own studio Lenfilm launched a broadside of attacks and demanded half his film be re-shot, though ultimately (more to spare additional costs than anything else) it remained unchanged.

Three years following a belated release, Ivan Lapshin was officially the “best Russian movie ever.” It was a remarkable turnabout for a director whose efforts had been — and in different ways would continue to be — perpetually thwarted, sometimes banned outright. In personal demeanor Guerman has been called “almost comically grim,” doubtless the result of so much uphill struggle. Yet that dour affect runs counter to the tenor of his most striking films, which are anarchic and borderline surreal, couching tragedy in absurdist humor and messy high spirits.

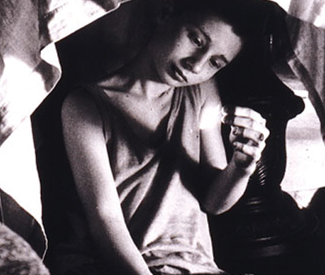

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts’ two-week series “War and Remembrance: The Films of Aleksei Guerman” brings to SF all of this slim oeuvre, little of which has been seen outside Russia save in festival appearances, cut form, or poor transfers that diminish the director’s mastery of complicated traveling shots in moody black and white.

Guerman (sometimes translated as “German”) was raised in Leningrad as the son of Yuri Guerman, a celebrated author who managed never to fall out of Stalin’s favor. Aiming to be a doctor, he hit cinema instead — first as a student and assistant, then co-directing 1967’s The Seventh Companion with the more established Grigori Aronov. The two fought throughout production of this sober drama about a Tsarist military officer converting to Socialist ideals, and Guerman has disavowed the end product.

He had sole credit on 1971’s Trial on the Road, another redemption tale — former Nazi collaborator surrenders to the Red Army, then re-infiltrates Axis forces to destroy an ammunitions train — but one judged insufficiently “heroic” by the government. It went unseen until 1986, when Gorbachev’s perestroika era liberated numerous long-banned films. A second World War II tale, Twenty Days Without War (1976), managed to escape censure with its melancholy portrait of a soldier on hometown furlough. It hinted at the looser, anecdotal, community-as-protagonist approach to come.

Still, Ivan Lapshin was a surprise leap toward humor, incident over conventional narrative, childhood memory as warm, boisterous yet melancholy blur á la Amarcord (1973) or Mon oncle Antoine (1971). (Though no sensibility could be more purely Russian than Guerman’s.) Based on stories by the director’s father, its main event is one that hasn’t happened yet when the film begins — Stalin’s first “Great Purge,” which would sweep away many of the moderately criminal or just eccentric figures portrayed in this fictive 1935 provincial town. Everyone here is a little mad, driven to distraction by the chaos of a grand collectivist experiment, spinning wild as if anticipating the cold smack down they were about to suffer. The amorphous structure some initially found off-putting now seems Ivan Lapshin‘s boldest, defining trait, the thing that keeps it floating in midair.

Despite that precedent, beleaguered Khrustalyov, My Car! — production dogged this time not by Soviet watchdogs, but by unreliable international funders — was greeted with walkouts and “disaster” judgments at its 1998 Cannes bow. Yet many of the same critics, overwhelmed at first by its wholesale abandonment of realism and coherence for phantasmagoria, pronounced it a masterpiece after second or third viewings. Framed like Ivan Lapshin as a child’s memory of (later) Stalinist life, its 150 minutes lunge still further toward a Fellini-like grotesque-carnival clutter of excesses, from the hospital where “unauthorized death [is] prohibited!” to the delivery truck in which our macho surgeon protagonist is shockingly assaulted in a spontaneous gay orgy. He’s ordered resuscitate the already dead Stalin, an impossible task capping an insane rule; the film’s last words (the director’s own?) are a voiced-over “Fuck it all!” Khrustalyov is a monumental clutter of energy and invention, so jerry-built that the fear it might collapse at any moment is part of its indelible rush.

Guerman is, logically enough, headed next to outer space — his adaptation of Soviet sci-fi classic Hard To Be a God took five years (starting in 2000!) to shoot, and is still being edited, thwarting hopes for Cannes premiere this month. Adversity may not have invaded his career by invitation, but one gets the sense that by now, at age 75, it is his most trusted collaborator.

WAR AND REMEMBRANCE: THE FILMS OF ALEKSEI GUERMAN

May 17-31, $6-$8

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

701 Mission, SF