FILM The demise of Ken Russell late last year at age 84 blew a few cobwebs off appreciation of his career, which had ever been beloved by cult-minded buffs but forgotten by most everyone else for some years. He hadn’t had a theatrical feature for two decades, and in his last years had been reduced to glorified home movies with titles like Revenge of the Elephant Man (2004) and The Fall of the Louse of Usher (2002). But for a while he was an inescapable, flamboyant, exasperating, and utterly unique presence in film, with even his detractors (who were legion) admitting his work could never be confused with anyone else’s.

In 1971 he was at his zenith as the scandal and big noise (frequently self blown) of British cinema, having had a great international success with 1969’s D.H. Lawrence adaptation Women in Love, which won a previously little-known Glenda Jackson her first Oscar, and a qualified one the next year with The Music Lovers, one of the increasingly outrageous classical-composer biopics he’d commenced making on the BBC and continued through 1975’s Lisztomania. (Which, featuring as it did Roger Daltry as pop star Franz Liszt having lovers dance like Rockettes on his giant phallus in one fantasy scene, and Wagner reincarnated as a Nazi Frankenstein in another, presumably exhausted that genre’s desecration possibilities even for Russell.) At the time, it seemed that 1971 was the year that killed off Old Hollywood and shat on its corpse. Movies like Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, Roman Polanski’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, John Boorman’s Deliverance, Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, Mike Nichols’ Carnal Knowledge, Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, Alan J. Pakula’s Klute, and Dusan Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism all pushed the envelope in terms of sex, violence, and nihilism.

Even in such company, Russell’s The Devils — which closes “The Second Coming of the Vortex Room,” the venue’s February series of religion-themed films — was an outstandingly bad trip, an assaultive experience as tainting and unwelcome to most as that phone-receiver tongue licking Heather Langenkamp’s ear in the original Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). The words “hallucinogenic,” “appalling,” and “tasteless” would be applied to nearly all Russell’s films, but never with such genuine revulsion as this one. Today, The Devils can be seen as perhaps his greatest, most cohesive work — being about hysteria, religious and sexual, it justified his trademark surreal excesses as no subject ever would again.

Based on an Aldous Huxley novel about actual historical events, it takes place in a 17th century France beset by plague, persecution, church corruption, and court decadence. Scheming to end walled city Loudon’s independence, Cardinal Richelieu seizes on an accusation made by an unstable abbess that the leading local priest had seduced her entire convent via black magic. After considerable torture, said priest, Urbain Grandier, was burned at the stake, despite recanted testimonies and widespread belief that only “crime” was being in ambitious Richelieu’s way.

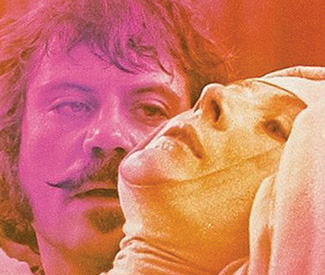

Russell depicts Grandier (played by his go-to bulldog Oliver Reed, practicing more restraint than usual) as a lusty breaker of celibacy vows, but also as a man of true conviction compared to the hypocritical displays of faith, morality, and community-mindedness around him. Mother Superior Jeanne (Vanessa Redgrave as you’ve definitely never seen her before) is a hunchback lost in fantasy and spite, having like many of her wards not chosen this vocation, but instead been abandoned to it — back then, well-born females whose family didn’t have enough dowry money to marry them off were forcibly “married” to Jesus instead.

The Devils is a fevered nightmare, unrelentingly grotesque and claustrophobic. (Russell had the inspiration of hiring Derek Jarman as his production designer — not yet a director himself, the latter devised studio bound, abstract monochrome sets more vividly oppressive than any actual historic sites could have been.) It had to be heavily cut even before getting slapped with an X rating in the U.S., excised sequences like a mad convent orgy dubbed “The Rape of Christ” assumed lost until their re-discovery a decade ago. In England the film was banned from several districts. Nearly everywhere, critical response was bilious — reviewers felt violated, polluted, disgusted. The L.A. Times called it “a degenerate and despicable work of art,” others “pornographic” and “Satanic” outright.

Those gag reflexes were understandable. The Devils is flawed, mostly in its crudely satirical aspects. And its scalding majority impact is achieved in a hyperbolic manner that makes it very hard to separate the depiction of blasphemy from the embodiment of it. Yowling “I want to shock people into awareness. I don’t believe there’s any virtue in understatement!” to Time magazine that year, Russell cared little about clarifying that distinction.

A visual statement as singularly alarming as any canvas by Bosch or Bacon, its disturbance further heightened by avant-garde composer Peter Maxwell Davies’ striking score, The Devils would doubtless be more highly regarded today had it been one isolated case of delirium in an otherwise relatively sane director’s oeuvre. But the baroque excesses Russell flaunted under any circumstance, no matter how apt, made it seem just more of his reliable too muchness. The neglect his work has fallen into benefits this most serious of his features, as it allows The Devils to be seen clearly as a caterwaul of horror — not at supernatural possession but at the infinite human cruelty power and sanctimony can allow.

THE DEVILS

Thursday, Feb. 23, 8 p.m. (double-feature with Privilege, 1968), $7 donation

Vortex Room

1082 Howard, SF

Facebook: The Vortex Room