arts@sfbg.com

HAIRY EYEBALL The painter Margaret Kilgallen died in 2001; she was just 33 years old. A year later, critic Glen Helfand would write in the Guardian (“The Mission School,” 7/1/2002) a coming out party for Kilgallen, her husband Barry McGee, and friends such as Chris Johanson and Alicia McCarthy, whose scruffy, heartfelt, and street-influenced art had started to attract a popular following abroad as well as intense interest from beyond the Bay Area art world.

When an artist dies young, it is hard to not view their work through the lens of their cruelly curtailed biography. The work that remains is always haunted by speculation about what could have been. Posthumous exhibits will always be, to some extent, tributes, and those who write about that artist’s work face the very human impulse to eulogize, as well as the critical one to historicize.

This dilemma is especially true for Kilgallen and her art. In the decade since her untimely passing due to complications from breast cancer, the Mission School has been variously contested and embraced as both an aesthetic and historical category, and the artists Helfand associated with it have become well-known, frequently imitated, and displayed in increasingly prestigious venues. Kilgallen, along with Johanson and McGee (with whom Kilgallen had a daughter just three weeks before she died), is prominently featured in the Geffen Contemporary’s current, much-hyped summer blockbuster “Art in the Streets.” And viewers need only spend a few hours trolling Etsy to sense the larger stylistic impact the Mission School has had on a younger generation of creative types.

“Summer/Selections,” Ratio 3’s current exhibition of paintings by Kilgallen and the first San Francisco solo show of her work in 13 years, is a bittersweet homecoming, to be sure. But it’s also, like Kilgallen’s art, unsentimental — which is not the same as unfeeling. It’s a reminder that while time doesn’t heal all wounds, it can sometimes afford us enough distance to see with greater clarity those qualities of the departed that so compelled or moved us in the first place. And, undoubtedly, the soft power of Kilgallen’s talents as a sympathetic observer is fully on display here.

Like her contemporaries, Kilgallen culled much of her imagery from hand-painted storefronts and signage along Mission Street, thrift-scored printed matter, old-fashioned typography, and the hand-scrawled texts of the homeless and itinerant. But sometimes the signal-to-noise ratio in her larger pieces — the crazy quilts of painted and stitched-together canvas scraps, or even her wall murals — drowned out the delicacy and assuredness at work in each individual component.

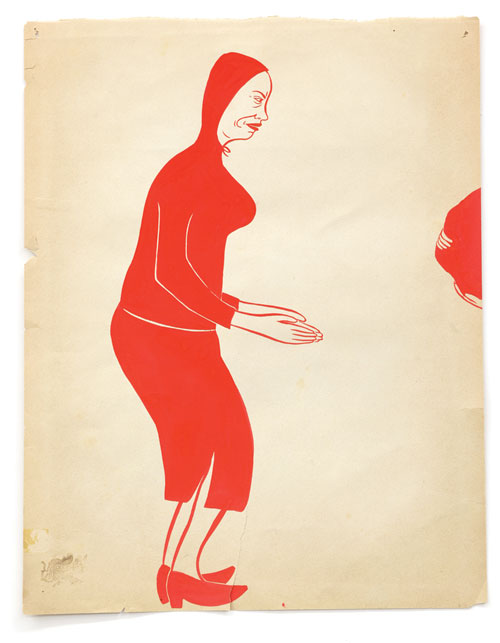

The remarkable selection of acrylic paintings — most from 2000 and all untitled — hanging in Ratio 3’s main space offers some much-welcome breathing room. They are single-subject studies of objects (groups of shoes, wigs, lips, trees, and plant life), simple repeating patterns (droplets, waves, grids), or (mostly) female figures on canvases made from discarded endpapers or repurposed grocery bags — another instance of Kilgallen’s sensitivity to the material grain of her surroundings.

Whether in the color gradations and tiny spiked edges of a leaf, or in the finely outlined toenails of a mule-clad foot, Kilgallen’s remarkable control over line and paint application imbues each canvas, even the simplest or most abstract, with an untold back-story. This is especially true of the women, who all have laugh lines but usually address the viewer with a tight-lipped smirk. If Kilgallen’s flora could have come from a children’s book, her women could pass as characters from a Dan Clowes comic.

The untitled collage pieces in the back room — smaller-scale examples of Kilgallen’s quilt-like assemblages of canvas — are more abstract, yet still retain the just-right sense of color, line and proportion on display in the other paintings. In one piece, from 1999, a single fluffy gray cloud is the only graphic break in a long expanse of sutured turquoise. Another from the same year resembles the collaged remains of a billboard’s past incarnations. But like all of the pieces in “Summer/Selections,” it feels wholly fresh.

I wish the same could be said of the recent work of Johanson, an SF expat and Kilgallen’s contemporary, whose current show at Altman Siegel is about as coherent and compelling as its title: “This, This, This, That.”

I have always preferred Johanson’s folksy takes on Sol LeWitt’s rainbow-hued precision over his text or figure-filled paintings, and there are plenty to take in here. The problem is one of editing.

For every piece — such as the carefully thought-out uneven grid of squares and rectangles “Fall Apart and Let It Go” (2011) — that feels like Johanson is trying to push himself and his explorations of color into a more formal direction, there is another that reads as an easy way out.

The acrylic and latex color shards of “Same Brain, Same Body, Different Day” (2011) nicely mirror the visible segments of the pressed grain of the wood they’re painted on, whereas “Celebration of Life Through Found Palette and Paint” (also 2011), a painted panel mounted to an upright, rainbow-colored wooden shipping palette, just feels lazy.

Certainly, many artists have made repetition a compelling cornerstone of their practice, extending their engagement with a single technique, approach, or material into a fruitful long-term relationship. Johanson, however, seems like he is simply in a rut, making more and more of the kind of art that first brought him wider renown with diminishing creative returns. Warhol did all right for himself in the 1970s, though, and I’m sure Johanson is doing just fine as well. But I know he’s capable of doing more.

MARGARET KILGALLEN: SUMMER/SELECTIONS

Through Aug. 5

Ratio 3

1447 Stevenson, SF

(415) 821-3371 www.ratio3.org

CHRIS JOHANSON: THIS, THIS, THIS, THAT

Through July 30

Altman Siegel

49 Geary, Fourth Floor, SF

(415) 576-9300, www.altmansiegel.com