johnny@sfbg.com

VISUAL ART/MUSIC I’m walking with Jim Marshall from his apartment in the Castro to his favorite restaurant just around the corner. The T-shirt he’s wearing showcases one of his more famous photos, of Johnny Cash flipping the bird. Marshall tells me and his friend and assistant of 13 years, Amelia Davis, about another time he was wearing the shirt. When the person he was with said he wanted one, he promptly took it off and gave it to him. We sit down at a table, I turn on my old tape recorder, and Marshall asks me for my first question. I say, “Well, it’s not a question, but I guess the first thing I could observe about you is that you’ll give someone the shirt off your back.” He laughs.

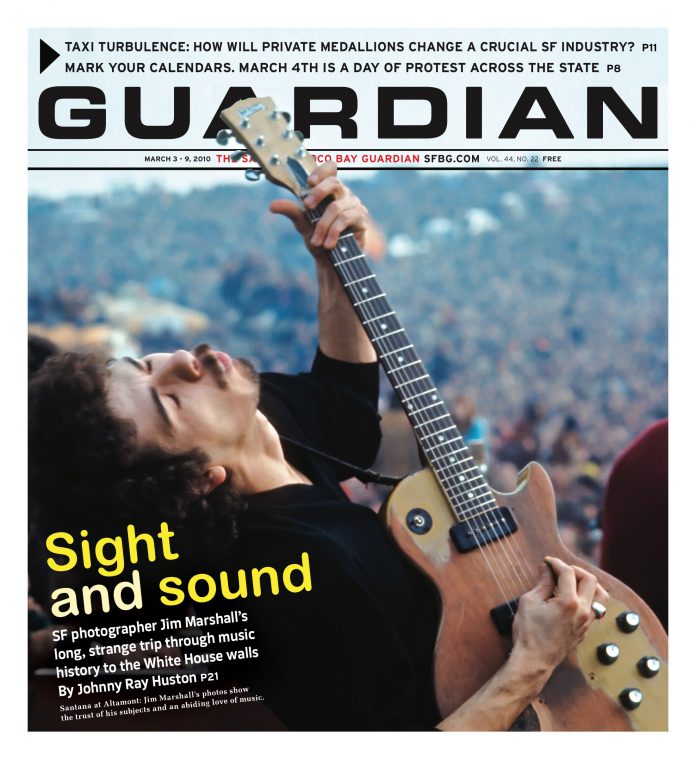

This story, itself born from a story from Marshall, suits an article about him, because as the title of his one of his new books makes clear, a major foundation of his photography is trust. Almost every page of Trust: Photographs of Jim Marshall (Vision On, 165 pages, $34.95) illustrates the deep implicit bond between photographer and subject in Marshall’s work, an element largely lacking from the prefab realm of music photography today. At times, this trust makes for startling juxtapositions: more than once Marshall’s camera catches a singer — Mahalia Jackson at Carnegie Hall; BB King at the Fillmore West; Janis Joplin at an outdoor concert in San Jose; Big Mama Thornton in a San Francisco recording studio; Nina Simone at New York Town Hall; Big Joe Turner at Berkeley Folk Festival — wholly unguarded, with arms open wide. The gesture reflects Marshall’s wholehearted embrace of music, an approach that makes his best images sing.

Marshall is a San Francisco photographer. “I was just starting out during the Beat era, in 1959, hanging out in North Beach,” he says. “They called me Jaguar Jim because I had a Jag 120. I photographed at the Hungry Eye. Lenny Bruce was the first roll of color I ever shot — 10 frames. Fantasy Records called me up about 10 years ago and said, ‘Jim, we’ve got some of your shots here.’ I figured there was some Creedence [Clearwater Revival] stuff, or Otis Redding. But there were 10 slides [of Bruce] that had been stuck under a cabinet for 35 years.” One of those 10 frames can be found in Match Prints (HarperCollins, 208 pages, $40), a just-published collaborative monograph that juxtaposes photos by Timothy White with photos by Marshall. In the shot, Bruce is standing before a brick wall, and he has his arms outstretched — almost like he’s expecting to be arrested. He’s on stage.

The back and forth between White’s photos and Marshall’s in Match Print — also on display at New York’s Staley-Wise Gallery later this month — is partly a conversation between on-the-scene verité images and the carefully set designed studio shots that tend to dominate magazine profiles. But it’s also about iconography and a memorable pose: Jim Morrison taking a drag from a cigarette for Marshall, Robert Mitchum inhaling (unlike Bill Clinton) for White. Match Prints has a casual sense of humor, evident in the pairing of Cash giving the finger with a White shot of Elizabeth Taylor flipping two birds after stepping out of a limo. (It’s also made clear by Alice Cooper’s playfully catty comments about his sister-in-leopard-skin-boots Lil’ Kim.) But the lingering moments of the book, and ironically, the most contemporary visions, come from older black and white Marshall photos, such as one of a zaftig Mama Cass in the back of a car, or bouffant-and-eyeliner beauty Little Richard lost in thought. Cass’s style and Richard’s drag are very Bay Area rock n’ roll 2010.

Marshall’s photography is 2010 enough to be lodged in the White House at the moment. President Obama has a Marshall shot of John Coltrane (also within Trust) on the wall. “He [Obama] had a White House photographer take a picture of him reflected in the [frame’s] glass,” Marshall explains with pride. “He signed it, ‘To Jim — I’m a big fan of your work … and Coltrane!” A little later, back at Marshall’s apartment, I look at this photo, and think of Obama’s image and trust. In deed, is the President doing right by the artists?

At lunch, Marshall zooms in on a telling moment from Obama’s recent State of the Union address. “He said, ‘This administration this year will end discrimination against gays in the military.’ The camera was on four generals and admirals in front of Obama. The whole place stood up and applauded. Those motherfuckers didn’t blink, didn’t move — nothing. They just sat there stone-faced. That’s the last thing they wanted to hear.”

The trust recorded in Trust is a different kind of commitment than one offered by a political figure. The photo of Coltrane — itself reflective, a bit melancholy, even haunted — that Obama sees himself within is a chief example. “Miles [Davis] saw my pictures of Coltrane and saw that John trusted me, and that was good enough for Miles,” Marshall explains, after I tell him about a great Davis interview in which he proclaimed that his favorite thing to do was watch white people act stupid on TV. “Miles, he didn’t like white people a whole lot. But for some reason he liked me. He said, ‘You’re as crazy as me.'” The truth is, in America, then and now, that’s as good a reason as any to like someone.

Truth is another strong element of Trust. Marshall’s investment in emotional truth means that his opinions aren’t always orthodox. Trust contains some photos of the infamous 1972 Rolling Stones American tour — “I must have done two pounds of blow on that tour,” Marshall crows — also documented by Robert Frank in the movie Cocksucker Blues. “I was never a big Robert Frank fan, and I’ll tell you why,” Marshall says, with trademark intimate candor. “As good as [Frank’s classic 1958 monograph] The Americans is — and it’s one of the all-time great photo books, damn near as great as [1955’s] Family of Man — what Frank failed to do is this: he didn’t show in one picture, as far as I can remember, the joy of being an American. It’s cynical. That bothers the shit out of me.”

As much as Frank, Marshall is a primary documentarian of 20th century America, well aware of a time when great filmmakers and photographers had enough faith in the government to work for it. “I had a Baby Brownie [camera] when I was a kid,” he says, when asked how he found his calling. “Everything was blurry — you had to take the picture when the sun was at your back. But I won a track meet, the 50 yard dash, and a guy was taking pictures for the school. He had an early Leica. When we go back to my apartment I’ll show you my scrapbook — it has pictures of cameras cut out of magazines and pasted on the paper, with their prices written in pencil. He took a picture of me that was razor sharp, and I thought, ‘This guy has a magic box.'”

Marshall’s Leica images have their own magic, evident in monographs such as Tomorrow Never Knows — The Beatles’ Last Concert (1987), Monterey Pop (1992), Not Fade Away (1997), Proof (2004), and Jazz (2005). Trust distinguishes itself by the dominance of color images — Marshall laughs heartily when I tell him that the blue sky found in a pair of outdoor concert photos of Joplin is a California blue. The color in Marshall’s photos is super-real, to re-deploy a word Anthony DeCurtis applies to White in the introduction to Match Prints. It isn’t the cliché hallucinogenic vision found in so many recreations of drug trips or the ’60s, but instead an extra intensity, utterly pure.

“The single greatest performance I ever saw in my life was Otis Redding in Monterey [at Monterey Pop in 1967],” Marshall says, as we page through Trust. “Brian Jones was there as a guest, and he said, ‘I think Mick [Jagger] is one of the greatest singers, and our band is one of the best, but personally, you couldn’t give me a million pounds to follow Otis Redding on stage.’ It was that shattering of a performance.” The photo we’re looking at as he says this is deep black and rich blue, with fists to the fore. It’s a cry — a shout — into the night.

A pair of photos in Trust capture confidences exchanged between Johnny Cash and a top-of-the-world Bob Dylan — a country-folk echo of the gestures of confidence between Marshall, Coltrane, and Davis. Marshall laughs when I tell him of an anecdote about the great folk artist-archivist and magician Harry Smith slamming the door of his Chelsea Hotel room in the young Dylan’s face with a loud “Fuck off!” When Marshall first began to photograph Cash and Dylan, the upstart musician was uncooperative, until his idol set him straight about the man behind the lens. “Bob Dylan respected without equivocation two people,” says Marshall. “Johnny Cash and Pete Seeger.” Indeed, Trust’s American history isn’t just a rock star history, it’s a secret history, a braided folk tale that extends from Elizabeth Cotten to the unlikely yet perfectly logical friendship between Sly Stone and Doris Day. Its stunning photos of the Carter Family can inspire a conversation about Redding’s and Anita Carter’s individually magnificent versions of “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long.”

Back at Marshall’s apartment, a photo of his late friend Tim Hardin at Woodstock broods as quietly as one of Hardin’s ballads, near the fireplace. “A million people around him, and he’s totally alone,” Marshall says, as if he took the shot yesterday. The hallway is lined with photos, not just by Marshall, but more often by famous acuaintances, many of them layered gestures of friendship that need no inscription. Marshall takes out his teenage scrapbook and sets it down on a table by his autographed images of Obama and Joe DiMaggio. “This was from the late 1940s!” he says, his voice rising in amazement. “Isn’t that a mindfuck?” It sure is. Another mindfuck would be for the best musicians and biggest personalities of the Bay Area to step in front of Marshall’s Leica today.

A NEW LOOK: JIM MARSHALL AND FRIENDS PUT THE FOCUS ON MS

VISUAL ART/EVENT This month, from March 5–19, one of Jim Marshall’s iconic images of Janis Joplin will be showcased in Union Square. The shot, of Joplin at the Palace of Fine Arts with arms outstretched as she sits atop a colorful Volkswagen Beetle, is just one of a number of prints being auctioned up for sale by photographers such as Baron Wolman, Michael Zagaris, Herb Greene, Robert Altman, Bobby Klein, and Marshall.

The cause is treatment of — and public awareness and conversation about — multiple sclerosis. All of the proceeds from sales of the photography goes to MSFriends, a grass-roots nonprofit begun by Marshall’s longtime friend Amelia Davis. Marshall hired Davis as an assistant knowing she had MS, and one encounter with Davis makes it easy to see why: she’s committed and dedicated. In the case of MSFriends, this dedication involves providing 24/7 telephone peer support, running an organization staffed by people who have MS, in an effort to help people with MS and others understand and respond to a misdiagnosed and misunderstood disease.

For more information about MSFriends Rock for MS and MSFriends, go to www.msfriends.org