Yes, it is summer. And yes, you look great in your tankini chewing ice cream and leathering your face. I am aware that school is out of session and out of fashion. And I know the institutional dinosaurs in tweed make you sneeze. But school is cool again — or at least it’s not as stale and stubborn as it once was.

I’m referring to experimental art schools, or “artist-initiated schools.” Their history lies in previous alternative art education models like the Bauhaus school or Black Mountain College, which served to explore other, more inventive ways of teaching and creating. Current models are everywhere. Coupled with the reach of today’s technologies they’ve grown into nebulous networks that spread like rhizomes in response to (or refusal of) what’s been called “a crisis in contemporary art education.”

Two recently published books address the height of this concern and the new shifts occurring within art education: Rethinking the Contemporary Art School (Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 234 pages, $25) and Art School (Propositions for the 21st Century) (MIT Press, 268 pages, $30). To get a grasp of how this has affected the Bay Area, I met with independent curator Joseph del Pesco to discuss some of the history and impetuses of these schools locally, including one of his own.

Pointing to Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius as a precursor, and his edict-turned-trope “art cannot be taught,” del Pesco says artist-initiated schools begin with “the idea that artists need an informal education,” which includes “informal spaces” away from art world market pressures and “collectors who cop the studios of the best MFA programs.”

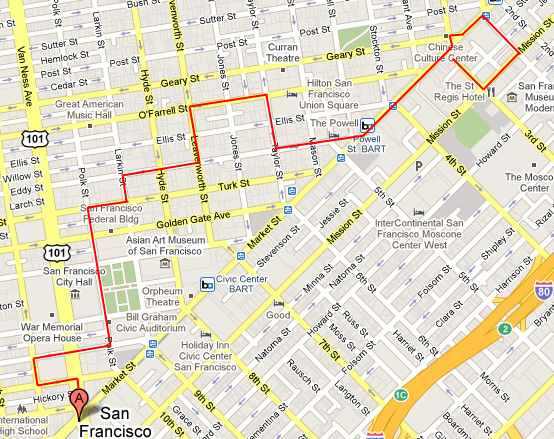

These informal spaces might take shape in a proper building or institution, but they’re also known to saunter in the streets, rub elbows in Chinatown bars, and wander nomadically from site to site. The loose, open structure of these spaces is meant to compliment and encourage the artist as autodidactic, self-orienting, and adaptive. This as opposed to the more conventional learning institutions that structure education through rigid class times, grades, diplomas, and linear teacher-to-student pedagogy.

Regarding local experimental school models, del Pesco cites the Independent School of Art as “the most important example in the Bay Area.” “ISA was run on a barter-based tuition system and you basically got a free education from Jon Rubin [ISA’s initiator], who was teaching at CCA and SFAI at the time.” Although the school only ran for two years (2004–06, at which point Rubin took a teaching position at Carnegie Mellon University), del Pesco emphasizes ISA’s ability to function completely untethered as a nomadic network of artists who successfully organized projects and events. ISA’s endeavors included black market auctions where students made and sold forgeries of famous art works, then used the money to fund more ISA projects.

Del Pesco’s own “experimental school-without-walls,” Pickpocket Almanack, is slightly less ambitious in its approach. Instead, this “school” (del Pesco is highly reluctant to use this term and insists on its metaphorical value to dismiss any anxieties it might harbor) functions more as an “algorithmic calendar.”

“I think some of the most interesting things we have here in the Bay Area are the public programs. The lectures, the panel discussions, the screenings — those are our creative strengths,” del Pesco says. “And part of Pickpocket Almanack — part of its impetus — was to take advantage of that.”

Just as the name implies — “stolen calendar” (the “k” added as a nod to Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack) — Pickpocket Almanack “steals” from the slew of free public programs offered by the Bay Area’s art institutions and organizes the best into individual courses via the prowess of an appointed team of “experts” or faculty. The faculty involved in Pickpocket’s spring 2010 season ran a wide gamut: Claudia Altman-Siegel, owner and director of Altman Siegel Gallery; Jim Fairchild, Modest Mouse guitarist; Amy Franceschini, artist and member of the Futurefarmers collective who organized Playshop, another Bay Area artist-initiated school; Renny Pritikin, curator and codirector during one of the best eras of the now defunct alternative space New Langton Arts; and Jerome Waag, artist and chef involved in the experimental restaurant collaborative OPENrestaraunt.

Partnered with SFMOMA, one might suspect Pickpocket Almanack’s “experimental” claim to be somewhat compromised. Although this relationship might carry with it a few bureaucratic implications, del Pesco assured me that Pickpocket’s faculty isn’t expected to include any of the museum’s events into its courses. If anything the pairing provides a consolation prize for Pickpocket’s participants (“students” is another term del Pesco avoids): an SFMOMA ID card that allows free access to any public program.

“It’s kind of like a gesture that makes the material real in some way,” del Pesco says. Since Pickpocket’s participants sign up through the website and discuss events primarily through e-mail, an initial launch event and final wrap-up meeting have also been incorporated to give some semblance of actual participation. But there’s no set structure. Some faculty have organized events outside of the course calendar, among them Fairchild, who facilitated a conversation with musician John Vanderslice.

While participating, as in any community setting, there’s always a fear of lame ducks. The misanthropic can technically remain anonymous throughout the course. “But there’s some incentive to actually meet each other to make it not a community but a kind of informal network of relationships,” del Pesco says. He likes to think of Pickpocket as “a special encounter with knowledge, where you don’t have the weight of school and education and a degree and grades and all that other shit. It’s self-guided; it’s social; it’s about the relationship between you, the people in the course, and the faculty — the informal production of knowledge and making visible certain events going on in the Bay Area.”

Pickpocket’s next season begins in September. So you have plenty of time to get dumb in the sun.