arts@sfbg.com

THEATER When caught riding Muni, one way to while away the time and ignore the lunatic seated next to you is to gaze out on the passing scene and its traffic, at the buildings and neighborhoods and detritus of the city, at all the lovers and loners, the shiny things people wear and drive and push and collect, as well as the tattered and forgotten stuff no one loves anymore.

It’s cheerier than remembering you’re stuck on a Muni bus, anyway. It’s a big ready-made rolling show and it’s only $2. True, Antenna Theater’s new ride, The Magic Bus, costs a little more, but then it comes with an added twist: time travel. I was stuck in traffic in 1968 last weekend. How many Muni riders can say that? Maybe only a dozen, tops.

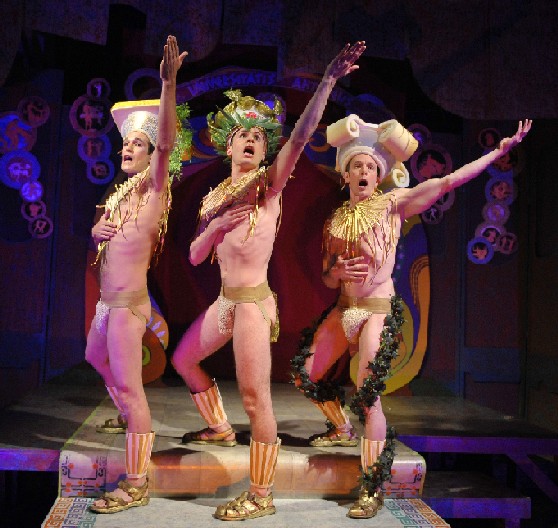

Copresented with Teacher with the Bus (Jens-Peter Jungclaussen’s wheel-bound extracurricular excursion line), The Magic Bus is Antenna Theater’s latest experiential outing. Scooping up audience-passengers in Union Square, the bus — painted in somewhat low-key shades of psychedelia and hosted by a genial “hippie flight attendant” played by either Rana Kangas-Kent or Sarah David — goes tripping through the city and back in time to the 1960s, with all their hoary contradictions, antecedents, and legacies. These include but are by no means limited to monkeys in orbit; astronauts on the moon; wars overseas; civil rights struggles at home; communes off the grid; and sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll seemingly everywhere.

The interior video and sound collage — expertly composed by a collaborative team of artists and Antenna’s artistic director Chris Hardman, who supplies the concept, script, sound design, and onboard 3-D artwork — makes the real-life scene outside the bus something like a palimpsest, only the past, rather than bleeding through to the surface, is cast over the present by video screens that automatically descend over the windows.

If there’s something a bit pat and predictable about such a project from the get-go, it would still be hard to reduce the overall effect of the ride to the admittedly too-familiar narrative it rehearses. That’s partly because you actually are moving, through a real city in real time, and stuff is happening outside those windows. The conversation between past and present is immediate and captivating.

Screens rise momentarily on the Financial District, for instance, where the Transamerica Pyramid building fills out the windows on one side of the bus and the odd pedestrian strolls by in front. Here, the voice-over introduces the pyramid structure, and the pyramid scheme it represents, amid the other soaring money towers that “reach so high as to block out the sun for most of the day.” Deceptively straightforward, the video narrative goes on to satirize, mock, and dissect the corporate ethos and the ideology of success American-style, as we hear Allen Ginsberg howling, “Molloch, whose blood is running money … “

Tried-and-true tropes, of course, and rather easy ones at that. But there’s no denying a certain willingness to embrace them, here at the edge of capitalism’s ever-expanding desert. Moreover, Magic Bus‘s narrative is lively and thoughtful even while limning well-traveled terrain. If “hobbit hippie” consciousness is with us still, in subtler but more widespread patterns of sustainable living, it’s now driven less by “a beautiful vision of the future,” notes the narrator, “than necessity.”

THE MAGIC BUS

Through August 8, $20–$25

Union Square, SF

(415) 332-8867