Frustrated by deep cuts to education spending and quality, momentum is building across California in support of the “Strike and Day of Action to Defend Public Education” on March 4.

Students, laborers, and faculty throughout the University of California system are trying to expand on last semester’s organizing efforts by strengthening ties to groups from all tiers of the public education system. But questions linger about the best way to proceed and what exactly the event should look like.

“I think that the regents and [UC President Mark] Yudof are very fearful of what would happen if the students and workers united. They could be unstoppable,” said Bob Samuels, president of the University Council-American Federation of Teachers (UC-AFT).

That collaboration is exactly what many grassroots organizers are hoping to achieve, although their central message is not limited to participants in the UC system alone. They argue that fee increases and cutbacks at the universities are symptomatic of a greater problem, namely the denigration of free and low-cost public education.

“This emerged as a movement of students and workers at the university level. What we’re doing now is going beyond the UCs,” said Blanca Misse, a graduate student and member of the Student Worker Action Team (SWAT).

By reaching out to members of preschool, K-12 public school, community college, and California State University communities, organizers hope to turn March 4 into a rallying moment for the entire public education system in the state. Organizers also want to ensure that the UC system isn’t funded at the expense of other institutions of public learning.

“We need to be fighting for money and political power,” Misse added. “The committees need to mobilize all of the fighting sectors and show them our strength.”

At the Jan. 17 meeting of the Berkeley March 4 organizing committee, one of many ad hoc groups set up across the state, a gathering of about 35 union members, graduate students, community activists, and undergraduates discussed what the day should look like locally. They also reported back on their attempts at organizing the local community, including garnering union support and reaching out to high school students.

Javier Garay noted that at a meeting of the Oakland Education Association, a union of public school workers, “89 percent of the nearly 800 attendees voted in solidarity with the March 4 Day of Action, possibly including a strike.”

Yet the most heated discussions centered on how to unite the interests and power of the university population behind the broader fight for public education funding.

During the meeting, Tanya Smith, president of the local chapter of the University Professional and Technical Employees union (UPTE), stressed the importance of “not being an ivory tower” by extending activism “beyond Berkeley’s campus and reaching out to the political center in Oakland.”

Student activist Nick Palmquist, a fourth-year development studies student at UC Berkeley, admitted that the “tuition issue” is a big motivating factor for college students. At the same time, he noted, “Students have a lot of potential to see the bigger picture. We’re trying to expand the consciousness of the movement.”

That movement stretches back to the beginning of the school year, when students realized that Yudof and the Board of Regents were planning on making up for the $814 million budget cut from 2008-09 and the additional $637 million cut in 2009-10 with layoffs, furloughs, and a possible fee hike.

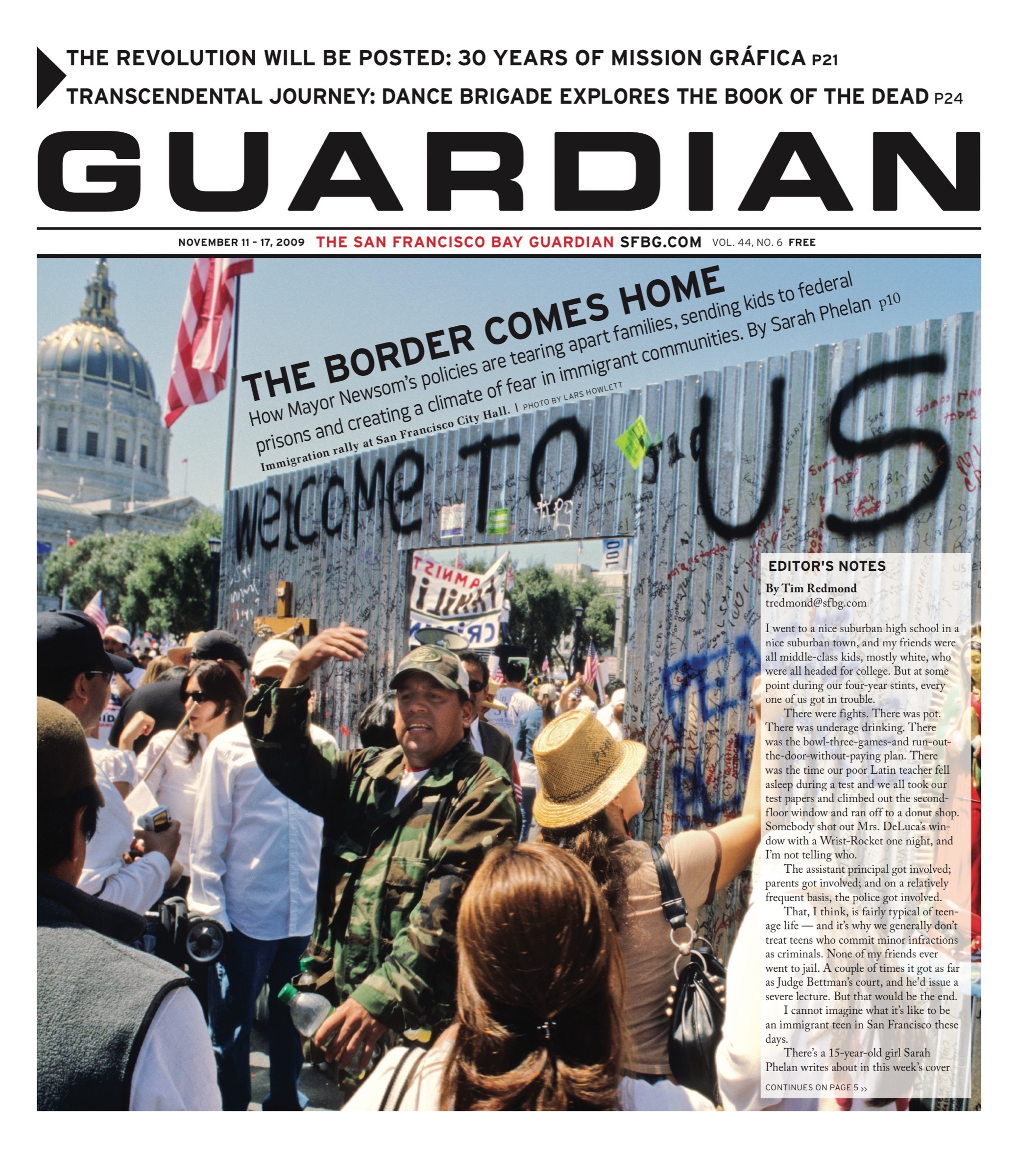

On Sept. 24, 2009, groups organized strikes and walkouts across the University of California system, including an estimated 5,000-person protest in the legendary Sproul Plaza at UC Berkeley.

Exactly one month later, several hundred people gathered on the Berkeley campus for the Mobilizing Conference to Save Public Education. According to the invitation, the purpose of the conference was “to democratically decide on a statewide action plan capable of winning this struggle, which will define the future of public education in this state, particularly for the working-class and communities of color.”

After an intense day of discussion, the body voted to establish March 4 as a “statewide strike and day of action.” Though it remains unclear how the different interests would come together (the call left demands and tactics open for debate), the message was clear: to save public education, diverse groups need to stand together cohesively.

Tensions escalated dramatically in November when the regents approved a 32 percent fee increase. At UCLA, where the regents held the meeting, an estimated 2,000 students gathered in demonstration and protest.

UC Berkeley student Isaac Miller told the Guardian, “I think we left there feeling like even though the fee increase went through, this is a long-term fight. It was really empowering to connect to students from all over the UC community.”

Meanwhile, a three-day protest at UC Berkeley culminated in a day-long occupation of Wheeler Hall on Nov. 20. As the protesters outside multiplied in support of the occupiers, they expressed solidarity with their causes as well as anger at the fee hike.

Callie Maidhof, a graduate student and spokesperson for the occupiers, said at the time, “One of the reasons behind this particular action is that students realized that not only is the state an unreliable partner, so is the administration. The only thing students can do at this point is reach out to each other.”

Maidhof was referring to a frequently repeated refrain from the regents and Yudof: “The state is an unreliable partner.” They argue that their hands are tied by the budget shortfall and the UC system has to figure out ways to sustain itself apart from increasingly erratic state funding. “The message is if the state fixes the budget, all our problems will be over,” said Mike Rotkin, mayor of Santa Cruz and a former lecturer at UC Santa Cruz.

So when a Jan. 21 San Francisco Chronicle article (“Regents to Back UC Students’ Protest at Capitol”) reported that the regents and Yudof agreed to stand alongside the students in Sacramento on the March 4 Day of Action, many were shocked and angered. “This is a complete turn-around for them,” Palmquist said. “They were never in support of our efforts. But now they feel threatened and they also feel like they can capitalize on them.”

In an open-letter response, several unions wrote back: “This is a cynical publicity stunt, and we do not buy it.”

Victor Sanchez, president of the UC Students Association (UCSA), said the article misrepresented what Yudof and the Regents said. “The regents and Yudof agreed to participate with students on a separate March 1 day of activism, not March 4,” he said. Calls and e-mail to Yudof’s office to confirm were unreturned at press time.

Sanchez explained that the March 1 activities are the culmination of UCSA’s annual Student Lobbying Conference, which takes place in Sacramento from Feb. 28–March 1. Its actions focus primarily on lobbying the Legislature. That approach is more in tune with the administration’s message that the problem lies in Sacramento.

UCSA’s demands include increasing funding for higher education by $1 billion, creating alternative sources of revenue through comprehensive prison reform, preserving the California grant program, and passing Assembly Bill 656.

Sponsored by Assembly Majority Leader Alberto Torrico (D-Fremont), AB 656 would place a severance tax on oil companies and divert revenues toward higher education. “It is strategic for us to focus resources in Sacramento, because that’s where the negotiations are happening,” Sanchez said. “But we also understand that we’re fighting a two-front war and need to hold both the Legislature and the administration responsible.

“At the end of the day, it is our event and our day of action,” he continued. “We made it clear we aren’t going to change our demands. We stand in solidarity with the March 4 organizers. We’re all advocating a common goal, and folks are going to apply complementary pressure. Our end goal is prioritizing education, and we need to move forward with that collective mentality.”

If all this seems confusing, that’s because it is. The groups that have formed in reaction to cuts to public education are numerous, amorphous, and have slightly different agendas. Some subscribe to the position that the fault and solution primarily rests in Sacramento, while others argue that the administration and appointed, rather than elected, regents are to blame. Most agree with Sanchez that both are part of the problem.

As community organizers build toward March 4, it is clear that the day will be significant. The real question is, if students can maintain their momentum and their newfound network with other sectors of public education, what will happen on March 5 and beyond?