Gay coming out novels are a dime a dozen. But The World of Normal Boys is something else. It’s a detailed, play-by-play exploration into the consciousness of a 13-year-old boy as he struggles to figure out who he is meant to be.

K.M. Soehnlein‘s book encapsulates all the pain and pleasure of growing up a little different, in a society still unsure of the benefits of diversity. Richard Labonte appreciated Soehnlein’s Lambda Award-winning literary effort for opening up the gate for a new type of coming out book – one that even though it’s set in a 1970s New Jersey suburb, it strikes a chord beyond its time and place.

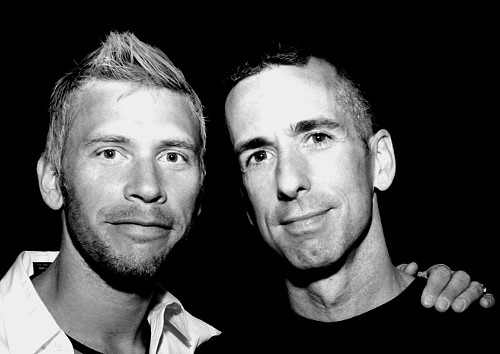

Local author K.M. Soehlein is the third author invited to participate in the Magnet Book Club (we’re posting interviews with the featured authors before their appearances). This month the discussion will take place at the GLBT History Museum across the street from Magnet. The GLBT History Museum will host Soehnlein on Monday, March 26 at 7:30pm for an intimate discussion of The World of Normal Boys. To lead up to that event, we spoke to the author.

SFBG Have older gay men reacted differently to the book than younger generations?

KS Definitely. Older readers like the book for capturing the era they grew up in, younger readers find it universal. We’ve all had a crush on the wrong guy who teases you by playing with your body but still treats you like shit. Recently a younger friend said that he just didn’t understand how the parents in the book could be so upset at having a gay son. That right there proves there has been a change in our culture too. We still see hateful news on TV but there’s been progress in certain bubbles, and those bubbles are what push us forward. Though family structures are still where most homophobia exists.

SFBG Did you have any reservations about writing a coming-of-age or coming out novel?

KS I don’t really consider it a coming of age story. Robin (the protagonist) goes from 13 to 14. That’s not really of age. And he never verbalizes that he is gay at the end. It’s more universal. We all have that moment of self-awareness, discovery, that moment of “I get how the world works.”

SFBG Do you consider yourself a gay author?

KS Yes. I’ve never shied away from that. Not to say it’s not a limiting label. But it’s like saying Obama is a black President. He is, but that’s not all that he is. I’m particularly drawn to telling gay stories, I’m not sure if I can write a thriller about an arms dealer.

SFBG What do you make of this post-gay mentality, the thought that we don’t need gay books or any gay culture for that matter?

KS I had another agent – a gay agent – tell me not to write another gay book. And that was just last year. But I think the publishing industry underestimates how loyal gay readers are.

SFBG What would you say to a twenty-year-old who is not interested in reading “gay books”?

KS I would ask how many gay books have you read? People who love to read, love to read broadly. Sure, now with gay characters on TV and the internet, they may not need a gay book like some people did thirty years ago. But books get inside the consciousness of individual characters. That’s one thing that books can do artistically that will never be obsolete.

SFBG Gay teens are coming out at a younger age now and with that has come more bullying. Is this a sign of the times – that with more visibility comes more backlash?

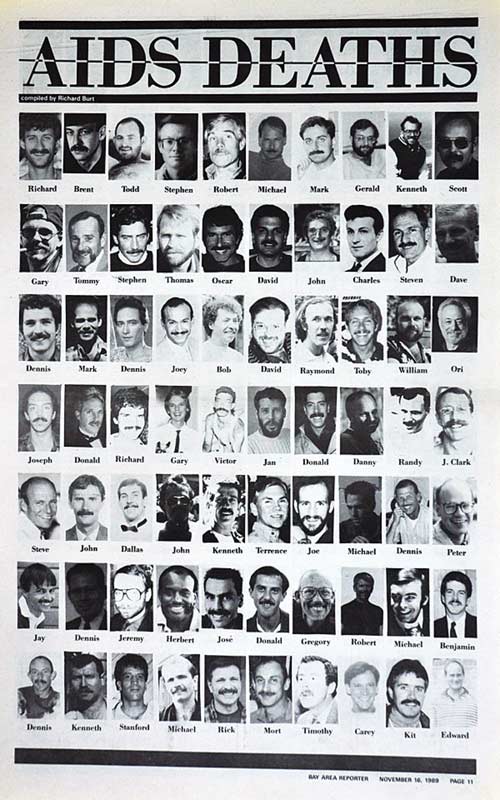

KS Back in the 70s, there wasn’t this type of awareness. Maybe gay teen suicides were underreported back then or maybe, in some ways, it’s the cost of visibility. When I lived in the East Village in the 1990’s, I was a member of ACT UP and founded Queer Nation. Then all of the sudden there was a wave of gay bashings. That was the definition of a backlash to our activism. There’s this symbiotic relationship between visibility and sacrifice.

SFBG As an author do you feel any moral responsibility?

KS The thing the author can do best is tell a character’s story. It’s hard to go into writing a novel with a political agenda, but you can have a political and cultural effect if you do your job very well. My next book is about being in ACT UP but it’s more about the characters. The political will come out of the historical and how these characters related to one another.

SFBG The World of Normal Boys is very sexual. Have you faced criticism to this explicit depiction of gay teen sexuality?

KS That was my intent, to talk honestly about sex among young adolescent guys. Just this week, a friend emailed me saying that she had loved the book but wondered if I ever thought about toning down the sexuality. To what? The PG version? It’s come to the point where we have internalized these cultural taboos around sexuality. I did a reading in New York and my whole family was there, so I started by saying all the dirty words that were in the excerpt I wanted to read (like “rimjob”). At the end I overheard my aunt shout, “I’ve heard them all before, I’ve been to the Village!” She’s this conservative, Republican, churchgoing, 70-year-old Italian lady who now likes me on Facebook. We really need to give readers more credit.

SFBG Though considered works of fiction, previous Magnet Book Club selections We the Animals and SoMa had some semi-autobiographical aspects. I’m wondering as to how much you drew from your own experience when writing The World of Normal Boys.

KS In the 80s I read queer books by Edmund White and Andrew Holleran, and I wanted to update what they were doing. My coming out happened more in college, but I had friends that came out at a young age, and no one had written about that. The time and place are autobiographical; I grew up in a suburb in Northern New Jersey. As a novelist it’s great how you can take things in your life and twist them around but still keep the essential truth.

K.M. Soehnlein will be Magnet Book Club’s guest of honor on Monday, March 26 at 7:30pm. Book club is open to the public and copies of The World of Normal Boys are available at Books, Inc. in the Castro for 15% off. Also available, a sequel titled Robin and Ruby. The GLBT History Museum is located at 4127 18th Street (between Castro and Collingwood) in San Francisco.