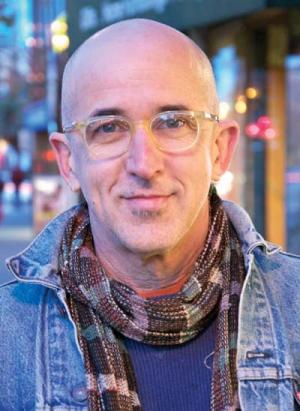

One of the strongest aspects of the film We Were Here is the intimacy and depth of its interviews (read our review here), so it’s with embarrassment and regret that I’m presenting this relatively casual Q&A with director David Weissman with the caveat that it’s been marred by a snafu. While transcribing, I discovered that the ‘Rec’ button on my ancient tape recorder had been triggered when it was in my carrying bag, and a sizable portion of the talk – including passages about archives, filmmaking, community, San Francisco, the cultural influence of The Cockettes, and a younger generation’s view of AIDS – had been replaced by the muffled sound of footsteps and traffic. The conversation is lost, but the story isn’t: We We Here is screening at the Castro Theatre through Thurs/3. Here’s some of what Weissman and I discussed.

SFBG What was the response to We Were Here like at Sundance?

David Weissman Sundance was great. We’d had a sneak preview at the Castro, and an even earlier one in Portland at the festival [the Portland Gay and Lesbian Film Festival] that I curate with Russ Gage up there, but Sundance was the first really mixed audience. The Salt Lake City screening was particularly fantastic.

SFBG How so?

DW You can feel the energy in the room, and people cry a lot at this movie. But I think that people cry in a way that by the end of the movie they feel good. That was one of the most important things to me – I didn’t want to make a movie that would just be devastating. It was important to me that it be inspiring. In almost every review and every response, people talk about it being uplifting.

Trailer for We Were Here:

SFBG In some ways We Were Here continues a tradition in San Francisco of oral history in documentary. I wanted to ask about your methodology in terms of doing interviews, because spoken interview accounts are a fundamental, powerful part of the film. You really devote time to the people whose stories you tell, or to flip it, those who tell their stories.

DW The only person I knew I was going to interview at the beginning was Ed [Wolf] and that’s because we’d known each other through doing HIV work, and I knew he had a passion about this story being told, and there was enough existing personal trust between us that I knew he would be an easy person to experiment with.

Right before I interviewed him, I woke up in the middle of the night with a start and thought, “Oh my god, I’ve done no research and have no notes. What am I thinking?” On The Cockettes [2002] we’d done tremendous research before each interview. Then I quickly calmed down and realized, “This is my story. This is my history. I lived through this entire thing.”

The interviews were totally unplanned and they went where they went. Rather than being conventional subject-object interviews, they were deep, mutually therapeutic conversations between people who shared a painful history.

SFBG How did you find and choose the film’s subjects?

DW It was completely intuitive. Other than Ed, the only way any of these people wound up in the film is that I bumped into them somewhere. In the course of conversation, I’d think, “Oh, you’d be good,” and [from] their unambiguous [affirmative] response, I’d decide to go with it. To some degree, their willingness to be interviewed is reflective of their generosity during the years of the epidemic. They clearly got a lot out of being interviewed personally. Having that kind of focus on such an intense part of one’s life for the first time is a powerful experience. But each of them really did it for the community and for the world.

SFBG Some of the answers are obvious, but how was making this film different from making The Cockettes, as an experience?

DW In many ways, the two films are very similar. The experience was different emotionally simply because there was so much pain involved in revisiting [We Were Here‘s] history. But both ultimately wound up being films in which a very large historical moment is evoked by a very small number of people, without a lot of extenuating materials to contextualize the times. The idea was to have the times emerge from the storytellers. There’s a great similarity in that choice.

The intention of the two films is also similar. In describing my intention with The Cockettes over the years, I’d say it had a twofold purpose, in validating the complexity and beauty of a period of time for the people who lived through it, and illuminating it in a rich and complex way for people who didn’t know anything about it. I’d use the exact same language for We Were Here.

The emotional aspect was much different. This film was much less celebratory and more wrenching. But there was something gratifying about being strong enough to engage with the material. The working experience with [co-director] Bill [Weber], the shared quality, was profoundly beautiful and extraordinary.

SFBG In making this film, I’d think any tasks or parts of the process you did on your own would be difficult.

DW When I see other documentaries and look at the credits, there’s name after name, but basically, it’s me and Bill. Each of us wears multiple hats. There’s also the production crew, Marsha [Kahm] and Loretta [Mollitor], who were incredible, and we had some archival help, too. But the big tasks of the movie belonged to me and Bill.

SFBG How did the film structure and approach of the film develop? Was it an intuitive process, as you suggested earlier?

DW The Cockettes had a clear narrative arc that Bill and I [as co-directors] agreed on from the beginning, and it didn’t have the burden of an entire community of people who had a stake in the story being told. The burden of how people would respond to We Were Here was a huge one that I worried about every day.

I don’t think Bill initially trusted that we could do [We Were Here] with this few people. From my vantage point, it was the fewer the better. And the less music the better. I came into it at the beginning saying, “No music at all.” Bill said, “You’re insane, we’re going to need some,” and I decided, “When we get there, let’s deal with it, but I want to start from zero.”

We evolved together, and Bill’s an enormously sensitive editor, both visually and with music. We were a good team. Bill said he kept having to unlearn his normal way of doing things, because some of what we were doing was so contrary – people are on screen for a long time, and they breathe, and they pause, and they make mistakes, and there is no augmentation of sentiment through music.

Sundance Film Festival: David Weissman:

SFBG Did you both do the film’s interviews?

DW I did all the interviews. With The Cockettes, we were co-directors. With We Were Here, I’m the producer and director, and Bill is the editor, and he got a co-director credit because his editorial role was so important.

SFBG Were there points while looking at archival material or doing interviews where you encountered anything that changed your ideas about what you were making?

DW Yes. One of the more conventional beliefs when making a film about recent events is that filmmakers generally prefer to use moving images instead of archival and still images. At a certain point, we shifted away from that, particularly when covering the pre-epidemic period in San Francisco. We focused on faces, and almost all of the faces are looking directly into the lens. That sense of personal intimacy is central to how the whole film works.

SFBG There’s a counterbalance that works well in direct relation to that decision – you move from those still images to the footage of people in clinics.

DW Some of that footage came from Tina Di Feliciantonio’s Living With AIDS [1987], and from Marc Huestis’s Chuck Solomon film [Chuck Solomon: Coming of Age, 1987]. I don’t know if we got any clinic footage from Ellen Seidler’s Fighting For Our Lives [1987], but we got a lot of footage from it. All of those films were made between 1985 and 1986. And there’s the footage from Silverlake Life [1993]. I still can’t bring myself to watch Silverlake Life all the way through. Bill did, and he chose the footage.

When I’m interviewing – and this is also true with The Cockettes – I sit with my ear literally on the camera. I want people looking as close to the lens as possible.