“Die techie scum.” Those words are sprayed ominously on sidewalks throughout San Francisco. They’re plastered on stickers stamped on lampposts. They’re even scrawled in the bathrooms of punk bars, the very establishments now populated by Google-Glass-wearing tech aficionados.

Journalists from San Francisco to New York have opined on the source of the hate: Is it the housing crisis? Tech-fueled gentrification? Rising inequality? Those same journalists later parachute into the tech industry to periodically peer at its soul: Is tech diverse enough? Is it sexist? Is it a true meritocracy?

Those issues are often looked at in a vacuum, but perhaps they shouldn’t be. Perhaps those problems are all interconnected, and solving tech’s diversity problem is also part of solving income inequality in San Francisco, giving longtime San Franciscans a chance to join the industry many now view as composed of outsiders and interlopers.

The average Silicon Valley tech worker makes about $100,000, according to Dice Holdings Inc., which conducts annual tech salary surveys. Opportunity in the tech sector may bolster San Francisco’s middle-income earners, vanishing like wayward sea lions from the city’s landscape. Statistics from the US Census Bureau show that 66 percent of the city is either very poor or very rich, showing a hollowing out of the middle class.

Some tech CEOs are addressing their employment needs with a foreign workforce. Mark Zuckerberg and a cadre of tech CEOs have lobbied Senate and House Republicans to reform immigration in their favor, hoping to lure out-of-country workers to fill tech’s employment vacancies. Politico reported Sean Parker gave upwards of $500,000 to Republicans in 2014, all for the cause of immigration reform.

Conversely, a movement is already underway to bring San Franciscans into tech’s fold, based on the idea of a win-win scenario: San Francisco’s public school students are overwhelmingly diverse and lower income, while the tech industry is not.

Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Yahoo recently released their diversity numbers, showing the companies are mostly white and male. This accusation has long haunted Silicon Valley.

Two years ago, Businessweek heralded the “Rise of the Brogrammer.” The stereotype is as follows: He preens as he programs in his popped collar, his startup funds fuel the city as he hunts “the ladies,” and he is insensitive toward women in the workplace in the most fratboy-like way imaginable.

Biz dev VP of @path just cracked lame jokes re: “nudie calendars,” frat guys + “hottest girls,” “gangbang” at #swsx talk. Cue early exit.

— Tasneem Raja (@tasneemraja) March 11, 2012

But while outlier brogrammer douche-bros certainly exist, whose classist opinions ignite widespread ire (think Greg Gopman’s statement comparing homeless people to “hyenas”), the real brogrammer threat is more insidious, more systemic.

“The brogrammer is always someone else,” wrote Kate Losse, a freelance journalist, in an April blog post. “He is THOSE Facebook guys who yell too loudly at parties and wave bottles in the air, he is not the nice, shy guy who gets paid 30 percent more because of his race, gender and appeal to the boy-genius fetishes of [venture capitalists].”

The overarching point of Losse’s article was this: There is a subtle sexism, and also racism, in the tech sector, which shuts out women and people of color. The looming stereotype of a douchey brogrammer can obscure the smaller, more indirect ways in which minorities and women are shut out of the industry.

Tech’s disturbing (but unsurprising) lack of diversity is being highlighted amid an economic backdrop that has resulted in widespread displacement of San Francisco’s working class and minorities.

Some are seeking to create opportunities for Bay Area communities of color within tech, as a way to even the scales. A swell of new applicants with programming skills — including people of color and women — may soon come knocking. But in the time it will take school-age coders to cycle through the first generation of new computer science classes, Silicon Valley is going to have to take a hard look in the mirror.

Some of the Bay Area’s hate toward tech may be rooted in a perceived lack of access. Longtime residents see a sea of newcomers, often white, often male, who aren’t pulling up a seat for minorities to join the new gold rush.

The age of the brogrammer is now, and it’s as socially progressive as the paleolithic era, meaning: not at all.

FAKE IT TIL YOU MAKE IT

Talk to anyone in the realm of new technology companies and startups, and they’ll surely tell you this: Tech is an inspiring, creative field, where pure skill is the key to unlocking any job you’d like. The dress style is casual (hoodies, of course) and the perks flow like wine (or energy drinks).

When the Guardian visited the CloudCamp social good hackathon, we saw video game arcade machines in the ground floor and beer flowing throughout. Another company, Hack Reactor, had desks attached to treadmills and a life coach on hand to mind employee health. These are accoutrements de rigeuer, stunningly standard. But tales of true Silicon Valley excess abound: One CEO offers employees free helicopter rides, many offer in-house chefs and extravagant travel.

Interns in Silicon Valley are enjoying huge perks like free meals, massages, swimming pools, nap pods: http://t.co/BdaaOdC95P

— Manufacturing.net (@MnetNews) June 10, 2014

Skill and ability alone are the keys to unlocking this lifestyle, the tech industry says. Workers’ fervor can take on an almost cult-like zeal.

“I think the sharing economy is addictive,” said Rafael Martinez-Corina, a panelist at the Share2014 sharing economy conference in May, touting tech’s biggest stars like AirBNB, Lyft, and Uber. “Once you get it, you want more and more. You get into car sharing, you want to get into food sharing, time sharing.”

He asked the audience, “Who else is addicted to sharing?”

Almost every hand went in the room shot right up. Cheers immediately followed. Hallelujah!

Mars Jullian, an engineer at AdRoll, told the Guardian that employees of tech companies with name-brand apps tend to exhibit more ego. AdRoll is a big player, but more behind the scenes, she said, giving her perspective on the attitudes of her fellow tech workers.

“Sometimes it seems tech people feel like they own the city,” she said. “I don’t know if that’s the right attitude to have. Sometimes it’s more important to be humble.”

One might forgive the tech workers for their enthusiasm. The industry, after all, has ushered in widespread transformation in business and communications, resulting in dramatic economic shifts. But with such a high concentration of wealth and influence in the Bay Area, the question of who gets to participate is key.

Google’s diversity numbers rocked the world outside Silicon Valley, but surprised few in the Bay Area. The behemoth is 70 percent male and 60 percent white, with Asians making up 30 percent of the company’s ethnic representation.

Soon after Google’s numbers were revealed, Facebook, Yahoo, and LinkedIn followed suit with their own diversity reports. Their numbers differ a bit from Google, showing more Asian employees, and slightly more women. The numbers look worse, however, when only technology jobs are factored in. The tech worker population among these companies is about 15 percent female.

Hadi Partovi, an early Facebook investor, now adviser, and ex-chief of Microsoft’s MSN, told the Guardian that despite the industry’s challenges, tech’s doors are open to people with skills, regardless of background.

“The computer doesn’t know if it’s being programmed by someone rich or poor, black or brown,” he told us in a phone interview. “A lawyer, for instance, is looked at more explicitly. Tech has the opportunity to be more meritocratic.”

But the tech sector’s pious belief that it functions as a world-changing meritocracy ignores a host of factors that serve to hinder inclusion.

Many have touted the education pipeline as the root cause of tech’s lack of diversity. The number of women pursuing science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields is stunningly low, 24 percent, according to the US Department of Commerce. African Americans and Latinos also lag far behind their white and Asian counterparts in completing their computer science degrees, according to studies by the East Bay nonprofit Level Playing Field Institute.

Considering Asian groups is important: the Level Playing Field Institute draws a distinction between represented and underrepresented minority groups, acknowledging that ethnicity, income and class intermingle in complex ways. It’s those underrepresented groups like women, Latinos and African Americans LPFI identifies as groups lacking in tech.

But the pipeline is only one part of the problem. Subtle (and not-so-subtle) misogyny and racism, often labeled micro-aggressions, pervade hiring.

Level Playing Field is focused on creating opportunity for people of color and women in STEM fields. In an extensive tech-industry study conducted in 2011, called “Hidden Bias in Information Technology Workplaces,” researchers concluded: “Despite widespread underrepresentation of women and people of color within the sector, diversity is not regarded as a priority.”

Surveying more than 645 engineers, the study’s authors found that white men were the most likely to believe that diversity was not a problem that needed addressing in the tech sector. The study also found that underrepresented people of color (Latinos and African Americans), and women were more likely to encounter exclusionary cliques, unwanted sexual teasing, bullying, and homophobic jokes.

Sometimes, these instances blow up for the world to see.

THE MIRROR-TOCRACY

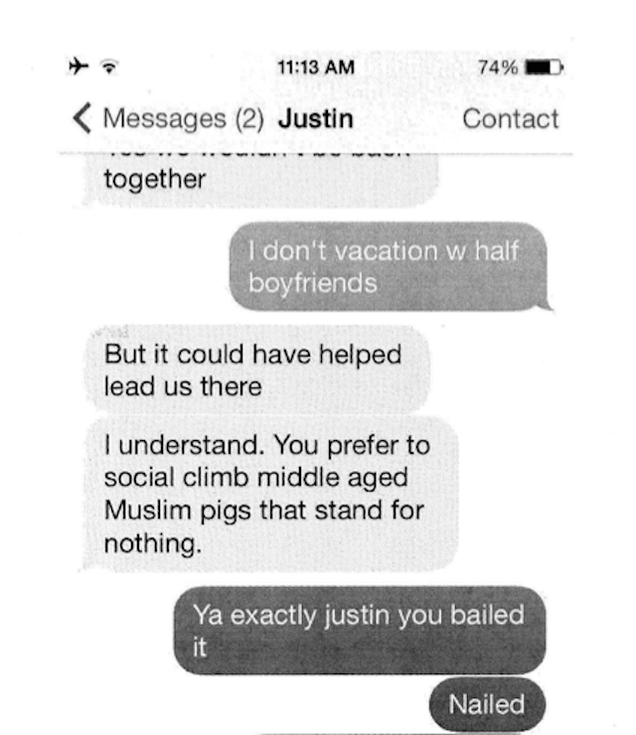

The workday text messages between Tinder’s co-founder Justin Marteen and former VP Whitney Wolfe went public after Wolfe sued Tinder, revealing the ugly waters women must sometimes navigate in tech. Marteen was allegedly harassing Wolfe over her new love interest, and Wolfe asked him to stop.

“Stop justin [sic]. Were at work,” Wolfe asked of Marteen, to which he replied, “Ur heartless… go talk to ur 26 year old fucking accomplished nobody. I’ll shit on him in life.”

He should have ended there. But he continued his rage at his ex-girlfriend.

“Hagsgagahaha so pathetic I even imagined a life w u. I actually thought u would be a good mother and wife. I have horrible judgement. He can enjoy my left overs,” he allegedly wrote. “You’re effecting my work environment,” she replied, “and this is very out of control. Please don’t do this during work hours.”

Besides an awful command of rudimentary spelling, the squabble showed the very real harassment women in tech are exposed to every day. When Wolfe went to Tinder CEO Sean Rad for help, she found herself out of a job.

Tinder is not an outlier, according to studies by Level Playing Field. Nor is it the only company to see its harassment go public. Earlier this year, GitHub’s CEO Tom Preston-Werner resigned after a former employee, Julie Ann Horvath, alleged she was harassed by him, his wife, and engineers.

While Github denied the allegations, Horvath was defiant: “A company can never own you. They can’t tell you who to fuck and who not to fuck. And they can’t take away your voice.”

But for every example of outright sexism or racism, there are multitudes of more subtle biases in the workplace. Level Playing Field’s studies found these biases are pervasive. They start as early as the hiring process.

Carlos Bueno is a former Facebook engineer, now tinkering behind the scenes at memSQL. He is of mixed ethnicity, Irish and Mexican, among others. “My father called us ‘Leprechan-os’,” he told us.

Bueno trained interviewers at Facebook, and like many there, he also conducted interviews. He said Facebook’s interview process was probably one of the best in the industry for screening out biases of the interviewer, but other companies were not as aware of bias as a problem.

“Every startup wants to be a big dog,” he said, describing the process. “But the point of a startup is to grow very large, very quickly. They don’t have time to learn. Some people take rules of thumb or investor advice and run with it.”

Paypal co-founder Max Levchin is looked to as a thought leader in the startup world. He touts the idea that diversity of perspective in a startup’s early phases can actually hurt its chances of success, hindering its speed in “endless debates.”

Paypal co-founder Peter Thiel once famously put it this way: “Don’t fuck up the culture.”

Bueno pointed to a real estate startup, 42Floors, as an example of a company adopting Levchin’s philosophy. It looks for potential hires who are a “cultural fit,” i.e., making sure the candidate and employer think alike.

One 42Floors interviewer explained this on the company blog: “I asked her how she was doing in the interview process and she said, ‘I’m actually still trying to get an interview. Well, I grabbed coffee with the founder, and I had dinner with the team last night, and then we went to a bar together.’ I chuckled. She was clearly confused with the whole matter. I told her, ‘Look, you just made it to the third round.'”

So the interview process for tech may involve coffee dates or “beer with the guys,” and the onus is on the interviewee to figure all of this out. Similar blog posts from 42Floors go on to call out interviewees who wear suits, or act too stodgy for their liking.

Is “pattern recognition” just sexism and racism?

Bueno refers to these hiring trends collectively as the “mirror-tocracy,” where startup founders hire people they like, people who remind them of themselves.

We spoke to Bueno extensively over burgers, but he put it best in his blog.

“You are expected to conform to the rules of The Culture before you are allowed to demonstrate your actual worth,” he wrote. “What wearing a suit really indicates is — I am not making this up — non-conformity, one of the gravest of sins. For extra excitement, the rules are unwritten and ever-changing, and you will never be told how you screwed up.”

Founders back up their faulty hiring practices with faulty logic. “It’s so hard to get in, if you get in you must be good,” Bueno said. “But those two statements don’t support each other.”

Some students of color training to code have already caught a glimpse of how the mirror-tocracy functions.

OPENING THE DOOR

Eight years ago, Kimberly Bryant moved to San Francisco to work in biotech. She moved to the city because she believed it to be more racially and economically diverse. She worked adjacent to Bayview Hunters Point, and has since revised her view of the city as a welcoming multicultural environment.

Instead, she found a city with an African American population dwindling below six percent in a city of over 800,000, and a gutted middle class. Latinos are moving out in greater numbers too. Over the last decade, 1,400 Latinos left the Mission District, according to a recent report on displacement by Causa Justa / Just Cause. In the same time, 2,900 white residents flooded in.

The displacement data reveals a significant parallel: The diverse ethnic groups Silicon Valley lacks in its employed ranks are the very same ethnic groups being priced out of San Francisco.

Seeking to mitigate the ethnic and gender disparity in tech, Bryant formed Black Girls Code, a student mentor and workshop program. It first opened up shop in the Bayview, but has sinced moved on.

“I really saw and experienced the true diversity of the community in Oakland,” Bryant told the Guardian, of the nonprofit’s new home. “It’s just an amazingly incredibly diverse community in terms of race and economy. What San Francisco used to be,” she added, “but is no longer.”

Black Girls Code teaches K-12 students rudimentary coding skills, providing instruction in Ruby and Python. Although companies like Google and others have opened their doors with welcoming arms, she said, convincing her students that the tech world is ready for them has been challenging.

When she brought her young students to an industry event, TechCrunch Disrupt, she dodged a minefield of fratboy-like behavior that made her students feel unwelcome, she said. This is the same event that heralded a prank app called “titstare,” which invited users (presumably male) to upload photos of themselves staring at women’s breasts.

The app was displayed on a stage before some of the most influential players in the tech industry, but Bryant’s students were in the audience too.

“They were shocked, like everyone there. It was disconcerting for the parents and the girls,” she said. Though she’s careful not to overplay the damage done (the girls “laughed awkwardly,” she said), the takeaway of the conference was that women and girls were not the intended participants. “It’s like a frathouse. I thought, ‘oh my god, this is like college all over again. This sucks.'”

Latino students at the Mission Economic Development Agency face similar barriers.

At Mission and 19th streets sits MEDA, a nonprofit that has long worked to help Mission residents gain a foothold in San Francisco workplaces. This begins even in the lobby, where a small kitchenette in the corner plays host to a chef who mixes up a mean ceviche, with spices admittedly leaving this reporter in tears. He aspires to open his own restaurant, and MEDA is helping him get there.

The upstairs houses a group of students called the Mission Techies. They seek support in their aspirations to enter the tech industry, but for them the dream may be further off than the chef’s.

Gabriel Medina, policy manager at MEDA, doesn’t mince words. These are the “challenge” kids, he said, but they’ve done him and program manager Leo Sosa proud.

The Mission Techies pull apart computers to learn about their innards.

Sosa described a visit from Google and Facebook engineers who taught his students rudimentary coding skills. One student, Jamar, was so engrossed in programming that one engineer asked: “Is he okay?!”

“Jamar is on the coding program, [and he’s] on fire,” Sosa told the Guardian, while sitting in a MEDA office.

But students like Jamar, an African American San Franciscan, face an uphill battle before they ever get to the step of applying for a job like one at Google.

After visiting some tech offices, the students felt less sure of themselves.

“They were like ‘I don’t see no black guys, I don’t see no Latinos. Leo, do you really think I can get a job here?'” Sosa told us. For them, the mirror-tocracy did not reflect an image they recognized.

By many measures, MEDA’s Mission Techies program is a success, taking kids of modest means and equipping them with digital skills that can aid their employment prospects. Mission Techies, Black Girls Code, and other programs such as Hack Reactor and Mission Bit all nip at the heels of the education pipeline leading to tech industry employment. They also share a common focus: They’re educating largely minority populations, often low-income, and located in the Bay Area.

The solution to tech’s diversity problem and to San Francisco’s displacement may spring from the same well: educate the people who live here to work in the local industry. But in order to do that effectively, afterschool and summer programs alone won’t do the trick.

The schools themselves need disruption.

WORKING TOGETHER

In the midst of the tech hub, the San Francisco Unified School District finds itself surrounded by tech allies. Still, change comes slowly.

Only five of SFUSD’s 17 high schools have computer science courses. Ben Chun, an MIT graduate and former computer science teacher at Galileo High School, told us the outlook is bleak without digital training in schools. Though kids sometimes teach themselves programming at home, most low-income students don’t have that opportunity.

“It’s a privilege thing,” he told us. If you have access to computers at home, you’re more likely to tinker and teach yourself. Those kids are more likely to be the Bill Gates of the future, he said, the self-starters and early computer prodigies.

“If you don’t have those things in place,” he said, “there’s a zero chance it will be you.”

When he first got to Galileo, his computer teacher predecessor taught word processing. But a lot has changed since 2006.

Partovi took his successes at Facebook and Microsoft and parlayed his money into a nonprofit called Code.org. The organization created its own coding classes for kids as young as 6, and compelled 30 school districts nationwide to create computer science courses based on its work.

Code.org’s tutorials have been played by millions of students.

Now it has its sights set on SFUSD’s 52,000 students, potentially solving tech and the school’s problems at once.

“It would for sure level that diversity gap,” Partovi told the Guardian. “All of the data released from Google, Yahoo, and others show a male-dominated industry. The pipeline of educated kids is actually much more diverse.”

Salesforce.com, whose CEO Marc Benioff is a San Francisco native, is also working with the school district on a tech solution, donating $2.7 million to spur that change.

But integrating tech in the district is slow, and likely years away. The district needs state standards to require computer science, something SFUSD Superintendent Richard Carranza has already lobbied Gov. Jerry Brown to change.

“The demand [for computer science classes] is coming from everywhere,” Carranza told us, including parents, students, the tech industry, and city leaders.

“What makes it a game changer is the partnership with our tech partners,” he said. “It gives our students the opportunity to interact elbow to elbow with people doing computer science out in the real world.”

But the tech workers those students are interacting with, though well meaning, remain the domain of the brogrammers. Will they hire SFUSD graduates with computer science skills when and if they’re ready? Will they be the right “culture fit?”

“There’s definitely a libertarian thread, a free market, red-toothed nature of things [in tech],” Bueno told us. “Talking to people in unguarded moments, that definitely leaks out. You’re not going to convince anyone by singing kumbaya and holding hands.”

But logical tech workers need look no further than the current numbers facing Silicon Valley to see the need to reach beyond their in-groups: 1.2 million new tech jobs will be created by 2020, studies from the US Department of Labor show. At the same time, 40 percent of the United States will be Latino and black by 2040.

When the minority is the majority, the brogrammers may become a dying species.