OPENING

The Adjustment Bureau In this drama adapted from a Philip K. Dick story, a congressman (Matt Damon) and a dancer (Emily Blunt) fall in love, much to the annoyance of the mysterious suits (portrayed by Mad Men‘s John Slattery, among others) tasked with controlling the politician’s destiny. (1:39) Marina, Piedmont, Shattuck.

Beastly Beauty (Vanessa Hudgens) meets beast (Alex Pettyfer) in this teen-oriented drama. Neil Patrick Harris is also involved, hopefully playing a singing tea kettle. (1:35)

Carmen in 3D Bizet’s popular opera hits the big screen, thanks to RealD and London’s Royal Opera House. (2:55)

I Am File in the dusty back drawer of An Inconvenient Truth (2006) wannabes. The cringe-inducing, pretentious title is a giveaway — though the good intentions are in full effect — in this documentary by and about director Tom Shadyac’s search for answers to life’s big questions. After a catastrophic bike accident, the filmmaker finds his lavish lifestyle as a successful Hollywood director of such opuses as Bruce Almighty (2003) somewhat wanting. Thinkers and spiritual leaders such as Desmond Tutu, Howard Zinn, UC Berkeley psychology professor Dacher Keltner, and scientist David Suzuki provide some thought-provoking answers, although Shadyac’s thinking behind seeking out this specific collection of academics, writers, and activists remains somewhat unclear. I Am‘s shambling structure and perpetual return to its true subject — Shadyac, who resembles a wide-eyed Weird Al Yankovic — doesn’t help matters, leaving a viewer with mixed feelings, less about whether one man can work out his quest for meaning on film, than whether Shadyac complements his subjects and their ideas by framing them in such a random, if well-meaning, manner. And sorry, this film doesn’t make up for Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994). (1:16) Lumiere, Shattuck, Smith Rafael. (Chun)

*Last Lions It’s hard being a single mom. Particularly when you are a lioness in the Botswana wetlands, your territory invaded and mate killed by an invading pride forced out of their own by encroaching humanity. Add buffalo herds (tasty yes, but with sharp horns they’re not afraid to use) and crocodiles (no upside there), and our heroine is hard-pressed to keep herself alive, let alone her three small cubs. Derek Joubert’s spectacular nature documentary, narrated by Jeremy Irons (in plummiest Lion King vocal form) manages a mind-boggling intimacy observing all these predators. Shot over several years, while seeming to depict just a few weeks or months’ events, it no doubt fudges facts a bit to achieve a stronger narrative, but you’ll be too gripped to care. Warning: those kitties sure are cute, but this sometimes harsh depiction of life (and death) in the wild is not suitable for younger children. (1:28) Embarcadero. (Harvey)

*Machotaildrop Every once in a while you see the Best Film Ever Made. Meaning, the movie that is indisputably the best film ever made at least for the length of time you’re watching it. Illustrative examples include Dr. Seuss musical The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953), Superstar (Todd Haynes’ 1987 Barbie biopic about Karen Carpenter), Nina Paley’s 2008 animation Sita Sings the Blues, several Buster Keaton vehicles, and Paul Robeson sightings — anything that delights unceasingly. Now there is Machotaildrop, which the Roxie had the excellent sense to book for an extended run after its local debut at SF IndieFest, a year and a half after its premiere at Toronto mystifyingly failed to set the entire world on fire. Corey Adams and Alex Craig’s debut takes place in a gently alternative universe where pro skateboarders play pro skateboarders who aspire to belonging in the media kingdom and island fiefdom of ex-tightrope-walking corporate titan the Baron (James Faulkner). Such is the lucky fate of gormless small-town lad Walter (Anthony Amedori), though naturally there proves to be something sinister going on here to kinda drive the kinda-plot along. When that disruption of skating paradise takes central focus after about an hour, what was hitherto something of pure joy — a genial, laid-back surrealist joke without identifiable cinematic precedent — becomes just a wee more conventional. But Machotaildrop still offers fun on a level so high it’s seldom legal. (1:31) Roxie. (Harvey)

Nora’s Will There’s certainly something to be said for the uniqueness of Nora’s Will: I can’t think of any other Mexican-Jewish movies that cover suicide, Passover, and cooking with equal attention. But while it sounds like the film is overloaded, Nora’s Will is actually too subtle for its own good. It meanders along, telling the story of the depressed Nora, her conflicted ex-husband, and the family she left behind. When the movie focuses on the clash between Judaism and Mexican culture, the results are dynamic, but more often that not, it simply crawls along. It’s not that Nora’s Will is boring: it’s just easily forgettable, which is surprising given its subject matter. Meanwhile, it walks that fine line between comedy and drama, never bringing the laughs or the emotional catharsis it wants to offer. The only real reaction it inspires is hunger, particularly if the idea of a Mexican-Jewish feast sounds appealing. Turns out “gefilte fish” is the same in every language. (1:32) Albany, Bridge, Smith Rafael. (Peitzman)

*Of Gods and Men It’s the mid-1990s, and we’re in Tibhirine, a small Algerian village based around a Trappist monastery. There, eight French-born monks pray and work alongside their Muslim neighbors, tending to the sick and tilling the land. An emboldened Islamist rebel movement threatens this delicate peace, and the monks must decide whether to risk the danger of becoming pawns in the Algerian Civil War. On paper, Of Gods and Men sounds like the sort of high-minded exploitation picture the Academy swoons over: based on a true story, with high marks for timeliness and authenticity. What a pleasant surprise then that Xavier Beauvois’s Cannes Grand Prix winner turns out to be such a tightly focused moral drama. Significantly, the film is more concerned with the power vacuum left by colonialism than a “clash of civilizations.” When Brother Christian (Lambert Wilson) turns away an Islamist commander by appealing to their overlapping scriptures, it’s at the cost of the Algerian army’s suspicion. Etienne Comar’s perceptive script does not rush to assign meaning to the monks’ decision to stay in Tibhirine, but rather works to imagine the foundation and struggle for their eventual consensus. Beauvois occasionally lapses into telegraphing the monks’ grave dilemma — there are far too many shots of Christian looking up to the heavens — but at other points he’s brilliant in staging the living complexity of Tibrihine’s collective structure of responsibility. The actors do a fine job too: it’s primarily thanks to them that by the end of the film each of the monks seems a sharply defined conscience. (2:00) Embarcadero. (Goldberg)

Rango Pirates of the Caribbean series director-star duo Gore Verbinski and Johnny Depp re-team for this animated comedy about a chameleon’s Wild West adventures. (1:47) Presidio.

Take Me Home Tonight Just because lame teen comedies existed in the ’80s doesn’t mean that they need to be updated for the ’10s. Nary an Eddie Money song disgraces the soundtrack of this unselfconscious puerile, pining sex farce — the type one assumes moviemakers have grown out of with the advent of smarty-pants a la Apatow and Farrell. Take Me Home Tonight would rather find its feeble kicks in major hair, big bags of coke, polo shirts with upturned collars, and “greed is good” affluenza. Matt (Topher Grace) is an MIT grad who’s refused to embrace the engineer within and is instead biding his time as a clerk at the local Suncoast video store when he stumbles on his old high school crush Tori (Teresa Palmer), a budding banker. In an effort to impress, he tells her he works for Goldman Sachs and trails after her to the rip-roaring last-hooray-before adulthood bash. Pal Barry (Dan Fogler) gets to play the Belushi-like buffoon when he swipes a Mercedes from the dealership he just got fired from, and ends up with a face full of powder in the arms of a kinky ex-supermodel (Angie Everhart). Despite cameos by comedians like Demetri Martin and a trailer and poster that make it all seem a bit cooler than it really is, Take Me Home Tonight doesn’t really touch the coattails of Jonathan Demme or even Cameron Crowe — in the hands of director Michael Dowse, it feels nowhere near as heartfelt, rock ‘n’ roll, or at the very least, cinematically competent. (1:37) California. (Chun)

*Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives See “Something Wild.” (1:53) Sundance Kabuki.

When We Leave See “Choose or Lose.” (1:59) Opera Plaza, Shattuck.

ONGOING

*Another Year Mike Leigh’s latest represents a particularly affecting entry among his many improv-based, lives-of-everyday-Brits films. More loosely structured than 2008’s Happy-Go-Lucky, which featured a clear lead character with a well-defined storyline, the aptly-titled Another Year follows a year in the life of a group of friends and acquaintances, anchored by married couple Tom (Jim Broadbent) and Gerri (Ruth Sheen). Tom and Gerri are happily settled into middle-class middle age, with a grown son (Oliver Maltman) who adores them. So far, doesn’t really sound like there’ll be much Leigh-style heightened emotion spewing off the screen, traumatizing all in attendance, right? Well, you haven’t met the rest of the ensemble: there’s a sad-sack small-town widower, a sad-sack overweight drunk, a near-suicidal wife and mother (embodied in one perfect, bitter scene by Imelda Staunton), and Gerri’s work colleague Mary, played with a breathtaking lack of vanity by Lesley Manville. At first Mary seems to be a particularly shrill take on the clichéd unlucky-in-love fiftysomething woman — think an unglamorous Sex in the City gal, except with a few more years and far less disposable income. But Manville adds layers of depth to the pitiful, fragile, blundering Mary; she seems real, which makes her hard to watch at times. That said, anyone would be hard-pressed to look away from Manville’s wrenching performance. (2:09) Shattuck. (Eddy)

Barney’s Version The charm of this shambling take on Mordecai Richler’s 1997 novel lies almost completely in the hang-dog peepers of star Paul Giamatti. Where would Barney’s Version be without him and his warts-and-all portrayal of lovable, fallible striver Barney Panofsky — son of a cop (Dustin Hoffman), cheesy TV man, romantic prone to falling in love on his wedding day, curmudgeon given to tying on a few at a bar appropriately named Grumpy’s, and friend and benefactor to the hard-partying and pseudo-talented Boogie (Scott Speedman). So much depends on the many nuances of feeling flickering across Giamatti’s pale, moon-like visage. Otherwise Barney’s Version sprawls, carries on, and stumbles over the many cute characters we don’t give a damn about — from Minnie Driver’s borderline-offensive JAP of a Panofsky second wife to Bruce Greenwood’s romantic rival for Barney’s third wife Miriam (Rosamund Pike). A mini-who’s who of Canadian directors surface in cameos — including Denys Arcand, David Cronenberg, and Atom Egoyan — as a testament to the respect Richler commands. Too bad director Richard J. Lewis didn’t get a few tips on dramatic rigor from Cronenberg or intelligent editing from Egoyan — as hard as it tries, Barney’s Version never rises from a mawkish middle ground. (2:12) Opera Plaza. (Chun)

Big Mommas: Like Father, Like Son (1:47) 1000 Van Ness.

Biutiful Uxbal (Javier Bardem) has problems. To name but a few: he is raising two young children alone in a poor, crime-beset Barcelona hood. He is making occasional attempts to rope back in their bipolar, substance-abusive mother (Maricel Álvarez), a mission without much hope. He is trying to stay afloat by various not-quite legal means while hopefully doing the right thing by the illegals — African street drug dealers and Chinese sweatshop workers — he acts as middleman to, standing between them and much less sympathetically-inclined bossmen. He’s got a ne’er-do-well brother (Eduard Fernandez) to cope with. Needless to say, with all this going on (and more), he isn’t getting much rest. But when he wearily checks in with a doc, the proverbial last straw is stacked on his camelback: surprise, you have terminal cancer. With umpteen odds already stacked against him in everyday life, Uxbal must now put all affairs in order before he is no longer part of the equation. This is Alejandro González Iñárritu’s first feature since an acrimonious creative split with scenarist Guillermo Arriaga. Their films together (2006’s Babel, 2003’s 21 Grams, 2000’s Amores Perros) have been criticized for arbitrarily slamming together separate baleful storylines in an attempt at universal profundity. But they worked better than Biutiful, which takes the opposite tact of trying to fit several stand-alone stories’ worth of hardship into one continuous narrative — worse, onto the bowed shoulders of one character. Bardem is excellent as usual, but for all their assured craftsmanship and intense moments, these two and a half hours collapse from the weight of so much contrived suffering. Rather than making a universal statement about humanity in crisis, Iñárritu has made a high-end soap opera teetering on the verge of empathy porn. (2:18) California, SF Center, Sundance Kabuki. (Harvey)

*Black Swan “Lose yourself,” ballet company head Thomas (Vincent Cassel) whispers to his leading lady, Nina (Natalie Portman), moments before she takes the stage. But Nina is already consumed with trying to find herself, and rarely has a journey of self-discovery been so unsettling. Set in New York City’s catty, competitive ballet world, Black Swan samples from earlier dance films (notably 1948’s The Red Shoes, but also 1977’s Suspiria, with a smidgen of 1995’s Showgirls), though director Darren Aronofsky is nothing if not his own visionary. Black Swan resembles his 2008 The Wrestler somewhat thematically, with its focus on the anguish of an athlete under ten tons of pressure, but it’s a stylistic 180. Gone is the gritty, stripped-down aesthetic used to depict a sad-sack strongman. Like Dario Argento’s 1977 horror fantasy, the gory, elegantly choreographed Black Swan is set in a hyper-constructed world, with stabbingly obvious color palettes (literally, white = good; black = evil) and dozens of mirrors emphasizing (over and over again) the film’s doppelgänger obsession. As Nina, Portman gives her most dynamic performance to date. In addition to the thespian fireworks required while playing a goin’-batshit character, she also nails the role’s considerable athletic demands. (1:50) Shattuck, Sundance Kabuki. (Eddy)

*Blue Valentine Sometimes a performance stands out and grabs attention for embodying a particular personality type or emotional state that’s instantly familiar yet infrequently explored in much depth at the movies. What’s most striking about Derek Cianfrance’s Blue Valentine is the primary focus it lends Michelle Williams’ role as the more disgruntled half of a marriage that’s on its last legs whether the other half knows that or not. Ryan Gosling has the showier part — his Dean is mercurial, childish, more prone to both anger and delight, a babbler who tries to control situations by motor-mouthing or goofing through them. But Williams’ Cindy has reached the point where all his sound and fury can no longer pass as anything but static that must be tuned out as much as possible so that things get done. Things like parenting, going to work, getting the bills paid, and so forth. It’s taken a few years for Cindy to realize that she’s losing ground in her lifelong battle for self-improvement with every exasperating minute she continues to tolerate him. Williams’ bile-swallowing silences and the involuntary recoil that greets Dean’s attempts to touch Cindy are the film’s central emotional color: that state in which the loyalty, obligation, fear, pity, or whatever has kept you tied to a failing relationship is being whittled away by growing revulsion. Gosling’s excellent stab at an underwritten part is at a disadvantage compared to Williams, who just about burns a hole through the screen. (1:53) Four Star, SF Center, Shattuck, Sundance Kabuki. (Harvey)

*Cedar Rapids What if The 40 Year Old Virgin (2005) got so Parks and Rec‘d at The Office party that he ended up with a killer Hangover (2009)? Just maybe the morning-after baby would be Cedar Rapids. Director Miguel Arteta (2009’s Youth in Revolt) wrings sweet-natured chuckles from his banal, intensely beige wall-to-wall convention center biosphere, spurring such ponderings as, should John C. Reilly snatch comedy’s real-guy MVP tiara away from Seth Rogen? Consider Tim Lippe (Ed Helms of The Hangover), the polar opposite of George Clooney’s ultracompetent, complacent ax-wielder in Up in the Air (2009). He’s the naive manchild-cum-corporate wannabe who never quite graduated from Timmyville into adulthood. But it’s up to Lippe to hold onto his firm’s coveted two-star rating at an annual convention in Cedar Rapids. Life conspires against him, however, and despite his heartfelt belief in insurance as a heroic profession, Lippe immediately gets sucked into the oh-so-distracting drama, stirred up by the dangerously subversive “Deanzie” Ziegler (John C. Reilly), whom our naif is warned against as a no-good poacher. Temptations lie around every PowerPoint and potato skin; as Deanzie warns Lippe’s Candide, “I’ve got tiger scratches all over my back. If you want to survive in this business, you gotta daaance with the tiger.” How do you do that? Cue lewd, boozy undulations — a potbelly lightly bouncing in the air-conditioned breeze. “You’ve got to show him a little teat.” Fortunately Arteta shows us plenty of that, equipped with a script by Wisconsin native Phil Johnston, written for Helms — and the latter does not disappoint. (1:26) California, Empire, Piedmont, Sundance Kabuki. (Chun)

Drive Angry 3D It says something about the sad state of Nicolas Cage’s cinematic choices when the killer-B, grindhouse-ready Drive Angry 3D is the finest proud-piece-o-trash he’s carried since The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009), which doesn’t say much — the guy works a lot. Here, in his quest to become the paycheck-happy late-Brando of comic book, sci-fi, and fantasy flicks, Cage gets to work that anguished hound-dog mien, while meting out the punishment against grotty Satanists, in this cross between Constantine (2005), bible comics, and Shoot ‘Em Up (2007). Out for blood and sprung from the deepest, darkest hole a bad boy can find himself in, vengeful grandpa Milton (Cage) — a sop for Paradise Lost readers — is determined to rescue his infant granddaughter. She’s in the hands of Jonah King (Billy Burke), a devil-worshipping cult leader with a detestable soul patch who killed Milton’s daughter and carries her femur around as a souvenir. Along for the ride is the hot-pants-clad hottie Piper (Amber Heard), who’s as handy with her fists as she is randy with the busboys (she drives home from work, singing along to Peaches’ “Fuck the Pain Away” — ‘nuf said), and trailing Milton is the mysterious Accountant (William Fichtner). Gore, boobs, fast cars, undead gunfighters, and cheese galore — it’s a fanboy’s fantasy land, as handed down via the tenets of our fathers Tarantino and Rodriguez — and though the 3D seems somewhat extraneous, it does come in, ahem, handy during the opening salvo. (1:44) 1000 Van Ness. (Chun)

The Eagle The mysterious fate of Rome’s Ninth Legion is all the rage lately — well, so sayeth the wee handful of people who caught Neil Marshall’s Centurion last year. For all who missed that flawed if worthy release, The Eagle arrives with a bigger budget and a bigger-name cast to puzzle out exactly what happened when thousands of Roman soldiers marched into what’s now Scotland, circa 120 AD, and never returned. The Eagle‘s Kevin Macdonald (2006’s The Last King of Scotland) bases his film on Rosemary Sutcliff’s popular children’s book, The Eagle of the Ninth, but the theory advanced here resembles Centurion‘s: the army was wiped out by hostile (and occasionally body-painted) natives. Much of The Eagle takes place decades after the disappearance, with the son of a Roman commander (Channing Tatum) scuttling past Hadrian’s Wall to seek truth, clear his family name, and reclaim a highly symbolic bronze eagle. Providing muscle and street smarts (or whatever the equivalent — backwoods smarts?) is slave Jamie Bell. The Eagle is handsomely shot, with some semi-thrilling PG-13 battle scenes, and any spin on Unsolved Mysteries: The Ninth Legion can’t really suck outright. But while Tatum has clearly clocked in the gym time to embody a Roman soldier, he doesn’t possess nearly enough depth (or any interesting qualities whatsoever) to play a character who supposedly has a lot of big emotions to work through. Bell does what he can with his sidekick role, short of performing CPR on his pulse-free costar, but it ain’t enough. Was Vin Diesel unavailable, or what? (1:54) 1000 Van Ness. (Eddy)

Even the Rain It feels wrong to criticize an “issues movie” — particularly when the issues addressed are long overdue for discussion. Even the Rain takes on the privatization of water in Bolivia, but it does so in such an obvious, artless way that the ultimate message is muddled. The film follows a crew shooting an on-location movie about Christopher Columbus. The film-within-a-film is a less-than-flattering portrait of the explorer: if you’ve guessed that the exploitation of the native people will play a role in both narratives, you’d be right. The problem here is that Even the Rain rests on our collective outrage, doing little to explain the situation or even develop the characters. Case in point: Sebastian (Gael García Bernal), who shifts allegiances at will throughout the film. There’s an interesting link to be made between the time of Columbus and current injustice, but it’s not properly drawn here, and in the end, the few poignant moments get lost in the shuffle. (1:44) Lumiere, Shattuck, Smith Rafael. (Peitzman)

The Fighter Once enough of a contenda to have fought Sugar Ray Leonard — and won, though there are lingering questions about that verdict’s justice — Dicky (Christian Bale) is now a washed-up, crack-addicted mess whose hopes for a comeback seem just another expression of empty braggadocio. Ergo it has fallen to the younger brother he’s supposedly “training,” Micky (Mark Wahlberg), to endure the “managerial” expertise of their smothering-bullying ma (Melissa Leo) and float their large girl gang family of trigger-tempered sisters. That’s made even worse by the fact that they’ve gotten him nothing but chump fights in which he’s matched someone above his weight and skill class in order to boost the other boxer’s ranking. When Micky meets Charlene (Amy Adams), an ambitious type despite her current job as a bartender, this hardboiled new girlfriend insists the only way he can really get ahead is by ditching bad influences — meaning mom and Dicky, who take this shutout as a declaration of war. The fact-based script and David O. Russell’s direction do a good job lending grit and humor to what’s essentially a 1930s Warner Brothers melodrama — the kind that might have had Pat O’Brien as the “good” brother and James Cagney as the ne’er-do-well one who redeems himself by fadeout. Even if things do get increasingly formulaic (less 1980’s Raging Bull and more 1976’s Rocky), the memorable performances by Bale (going skeletal once again), Wahlberg (a limited actor ideally cast) and Leo (excellent as usual in an atypically brassy role) make this more than worthwhile. As for Adams, she’s just fine — but by now it’s hard to forget the too many cutesy parts she’s been typecast in since 2005’s Junebug. (1:54) Four Star, 1000 Van Ness, SF Center, Sundance Kabuki. (Harvey)

Gnomeo and Juliet If you willingly see a movie titled Gnomeo and Juliet, you probably have a keen sense of what you’re in for. And as long as that’s the case, it’s hard not to get sucked into the film’s 3D gnome-infested world. Believe it or not, this is actually a serviceable adaptation of Shakespeare’s classic — minus the whole double-suicide downer ending. But at least the movie is conscious of its source material, throwing in several references to other Shakespeare plays and even having the Bard himself (or, OK, a bronze statue) comment on the proceedings. It helps that the cast is populated by actors who could hold their own in a more traditional Shakespearean context: James McAvoy, Emily Blunt, Maggie Smith, and Michael Caine. But Gnomeo and Juliet isn’t perfect — not because of its outlandish concept, but due to a serious overabundance of Elton John. The film’s songwriter and producer couldn’t resist inserting himself into every other scene. Aside from the final “Crocodile Rock” dance number, it’s actually pretty distracting. (1:24) 1000 Van Ness, Presidio, SF Center. (Peitzman)

*The Green Hornet I still don’t understand why this movie had to be in 3D, or what Cameron Diaz’s character has to do with anything, but I liked The Green Hornet in spite of myself. Only in Hollywood could artsy director Michel Gondry hook up with self-satisfied comedian Seth Rogen, who stars in and co-wrote this surprisingly amusing (if knowingly lightweight) superhero entry. After the death of his father (a megarich newspaper owner — how retro!), Rogen’s party boy Britt Reid decides, either out of boredom or misdirected rebellion, to become an anti-crime vigilante only pretending to be a criminal. (And that’s about as complicated as this movie gets.) Helping him, which is to say creating all of the cool cars and gadgets and single-handedly winning all of the fist fights, is Kato (Taiwanese actor Jay Chou, taking over the role Bruce Lee made famous). As himself, Reid is so obnoxious he pisses off newspaper editor Axford (Edward James Olmos); as the Hornet, he’s so obnoxious he pisses off actual crime boss Chudnofsky, played by movie highlight Christoph Waltz — more or less doing a Eurotrash twist on his Oscar-winning Inglourious Basterds (2009) Nazi. (1:29) SF Center. (Eddy)

Hall Pass There are some constants when it comes to a Farrelly Brothers movie: lewd humor, full-frontal male nudity, and at least one shot of explosive diarrhea. Hall Pass does not disappoint on the gross-out front, but it’s a letdown in almost every other way. Rick (Owen Wilson) and Fred (Jason Sudeikis) are married men obsessed with the idea of reliving their glory days. Lucky for them, wives Maggie (Jenna Fischer) and Grace (Christina Applegate) decide to give them a week-long “hall pass” from marriage. Of course, once Rick and Fred are able to go out and snag any women they want, they realize most women aren’t interested in being snagged by dopey fortysomethings. On paper, Hall Pass has the potential to be a sharp, anti-bro comedy. Instead, it wallows in recycled toilet humor that’s no longer edgy enough to make us squirm. At least there are still moments of misogyny to provide that familiar feeling of discomfort. (1:38) 1000 Van Ness, Presidio. (Peitzman)

How I Ended This Summer (2:04) Sundance Kabuki.

I Am Number Four Do you like Twilight? Do you think aliens are just as sexy — if not sexier! — than vampires? I Am Number Four isn’t a rip-off of Stephenie Meyer’s supernatural saga, but the YA novel turned film is similar enough to draw in that coveted tween audience. John (Alex Pettyfer) is a teenage alien with extraordinary powers who falls in love with a human girl Sarah (Dianna Agron). But they’re from two different worlds! To be fair, star-crossed romance isn’t the issue here: the real problem is I Am Number Four‘s “first in a series” status. Rather than working to establish itself as a film in its own right, the movie sets the stage for what’s to come next, a bold presumption for something this mediocre. It lazily drops some exposition, then launches into big, loud battles without pausing to catch its breath. I Am Number Four only really works if it gets a sequel, and we all know how well that turned out for The Golden Compass (2007). (1:44) 1000 Van Ness, Shattuck. (Peitzman)

*The Illusionist Now you see Jacques Tati and now you don’t. With The Illusionist, aficionados yearning for another gem from Tati will get a sweet, satisfying taste of the maestro’s sensibility, inextricably blended with the distinctively hand-drawn animation of Sylvain Chomet (2004’s The Triplets of Belleville). Tati wrote the script between 1956 and 1959 — a loving sendoff from a father to a daughter heading toward selfhood — and after reading it in 2003 Chomet decided to adapt it, bringing the essentially silent film to life with 2D animation that’s as old school as Tati’s ambivalent longing for bygone days. The title character should be familiar to fans of Monsieur Hulot: the illusionist is a bemused artifact of another age, soon to be phased out with the rise of rock ‘n’ rollers. He drags his ornery rabbit and worn bag of tricks from one ragged hall to another, each more far-flung than the last, until he meets a little cleaning girl on a remote Scottish island. Enthralled by his tricks and grateful for his kindness, she follows him to Edinburgh and keeps house while the magician works the local theater and takes on odd jobs in an attempt to keep her in pretty clothes, until she discovers life beyond their small circle of fading vaudevillians. Chomet hews closely to bittersweet tone of Tati’s films — and though some controversy has dogged the production (Tati’s illegitimate, estranged daughter Helga Marie-Jeanne Schiel claimed to be the true inspiration for The Illusionist, rather than daughter and cinematic collaborator Sophie Tatischeff) and Chomet neglects to fully detail a few plot turns, the dialogue-free script does add an intriguing ambiguity to the illusionist and his charge’s relationship — are they playing at being father and daughter or husband and wife? — and an otherwise straightforward, albeit poignant tale. (1:20) Clay, Shattuck, Smith Rafael. (Chun)

Inside Job Inside Job is director Charles Ferguson’s second investigative documentary after his 2007 analysis of the Iraq War, No End in Sight, but it feels more like the follow-up to Alex Gibney’s Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005). Keeping with the law of sequels, more shit blows up the second time around. As with No End in Sight, Ferguson adeptly packages a broad overview of complex events in two hours, respecting the audience’s intelligence while making sure to explain securities exchanges, derivatives, and leveraging laws in clear English (doubly important when so many Wall Street executives hide behind the intricacy of markets). The revolving door between banks, government, and academia is the key to Inside Job‘s account of financial deregulation. At times borrowing heist-film conventions (it is called Inside Job, after all), Ferguson keeps the primary players in view throughout his history so that the eventual meltdown seems anything but an accident. The filmmaker’s relentless focus on the insiders isn’t foolproof; tarring Ben Bernanke, Henry Paulson, and Timothy Geithner as “made” guys, for example, isn’t a substitute for evaluating their varied performances over the last two years. Inside Job makes it seem that the entire crisis was caused by the financial sector’s bad behavior, and this too is reductive. Furthermore, Ferguson does not come to terms with the politicized nature of the economic fallout. In Inside Job, there are only two kinds of people: those who get it and those who refuse to. The political reality is considerably more contentious. (2:00) Lumiere. (Goldberg)

Just Go With It Only within the hermetically sealed landscape of the Hollywood romantic comedy can a man’s sociopathic impulse (to lie about being unhappily married to every gullible young woman he sleeps with over the course of two action-filled decades) be smoothed over into a laughable character defect that the right woman will see through or look past and then cure him of. But here we are in Hollywood, or rather, in Beverly Hills, where, as depicted by Just Go With It, the moral continuum seems to range from plastic surgeons who perform good boob jobs to plastic surgeons who perform bad ones. Adam Sandler is one of the good-fake-boob kinds but also the liar liar, and Jennifer Aniston is the long-suffering office assistant and single mom who joins forces with him in the cause of smoothing out a wrinkle in his ersatz romantic life. This involves the construction of an improvisatory tissue of lies so vast that it envelops an entire fake blended family (including not one but two creepily precocious children) and necessitates a trip to Hawaii and nearly two hours of penile-implant, mammary-gland, and alimentary-canal humor to be untangled sufficiently for a happy ending. Sandler and Aniston have a decent comic rapport going, at least until the sappy, sick-making moment of truth, and this reviewer may have snickered at one or two moments, or even periodically throughout the film, but is deeply ashamed of it now. (1:56) 1000 Van Ness. (Rapoport)

Justin Bieber: Never Say Never 3D (1:45) 1000 Van Ness.

The King’s Speech Films like The King’s Speech have filled a certain notion of “prestige” cinema since the 1910s: historical themes, fully-clothed romance, high dramatics, star turns, a little political intrigue, sumptuous dress, and a vicarious taste of how the fabulously rich, famous, and powerful once lived. At its best, this so-called Masterpiece Theatre moviemaking can transcend formula — at its less-than-best, however, these movies sell complacency, in both style and content. In The King’s Speech, Colin Firth plays King George VI, forced onto the throne his favored older brother Edward abandoned. This was especially traumatic because George’s severe stammer made public address tortuous. Enter matey Australian émigré Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush, mercifully controlled), a speech therapist whose unconventional methods include insisting his royal client treat him as an equal. This ultimately frees not only the king’s tongue, but his heart — you see, he’s never had anyone before to confide in that daddy (Michael Gambon as George V) didn’t love him enough. Aww. David Seidler’s conventionally inspirational script and BBC miniseries veteran Tom Hooper’s direction deliver the expected goods — dignity on wry, wee orgasms of aesthetic tastefulness, much stiff-upper-lippage — at a stately promenade pace. Firth, so good in the uneven A Single Man last year, is perfect in this rock-steadier vehicle. Yet he never surprises us; role, actor, and movie are on a leash tight enough to limit airflow. (1:58) Albany, Embarcadero, Marina, 1000 Van Ness, Piedmont, Sundance Kabuki. (Harvey)

No Strings Attached The worst thing about No Strings Attached is its advertising campaign. An eyeroll-worthy tagline — “Can sex friends stay best friends?” distracts from the fact that this is a sharp and satisfying romantic comedy. Perhaps it’s not the most likely follow-up to Black Swan (2010), but Natalie Portman is predictably charming, and Ashton Kutcher proves he’s leading man material after all. They’re aided by an exceptional supporting cast, including indie darlings Greta Gerwig and Olivia Thirlby, and underrated comic actors Lake Bell and Mindy Kaling. No Strings Attached is a welcome return to form from director Ivan Reitman, who gave us classics like Ghostbusters (1984) before tainting his image with Six Days Seven Nights (1998) and My Super Ex-Girlfriend (2006). There are likely going to be many who will dismiss Reitman’s latest out of hand — and with those misleading trailers and posters, it’s hard to blame them. But I advise you to give No Strings Attached a chance: at the very least, it’ll counter the image of Portman tearing at a stubborn hangnail. (1:50) 1000 Van Ness. (Peitzman)

127 Hours After the large-scale, Oscar-draped triumph of 2008’s Slumdog Millionaire, 127 Hours might seem starkly minimalist — if director Danny Boyle weren’t allergic to such terms. Based on Aron Ralston’s memoir Between a Rock and a Hard Place, it’s a tale defined by tight quarters, minimal “action,” and maximum peril: man gets pinned by rock in the middle of nowhere, must somehow free himself or die. More precisely, in 2003 experienced trekker Ralston biked and hiked into Utah’s Blue John Canyon, falling into a crevasse when a boulder gave way under his feet. He landed unharmed … save a right arm pinioned by a rock too securely wedged, solid, and heavy to budge. He’d told no one where he’d gone for the weekend; dehydration death was far more likely than being found. For those few who haven’t heard how he escaped this predicament, suffice it to say the solution was uniquely unpleasant enough to make the national news (and launch a motivational-speaking career). Opinions vary about the book. It’s well written, an undeniably amazing story, but some folks just don’t like him. Still, subject and interpreter match up better than one might expect, mostly because there are lengthy periods when the film simply has to let James Franco, as Ralston, command our full attention. This actor, who has reached the verge of major stardom as a chameleon rather than a personality, has no trouble making Ralston’s plight sympathetic, alarming, poignant, and funny by turns. His protagonist is good-natured, self-deprecating, not tangibly deep but incredibly resourceful. Probably just like the real-life Ralston, only a tad more appealing, less legend-in-his-own-mind — a typical movie cheat to be grateful for here. (1:30) Opera Plaza. (Harvey)

*True Grit Jeff Bridges fans, resist the urge to see your Dude in computer-trippy 3D and make True Grit your holiday movie of choice. Directors Ethan and Joel Coen revisit (with characteristic oddball touches) the 1968 Charles Portis novel that already spawned a now-classic 1969 film, which earned John Wayne an Oscar for his turn as gruff U.S. Marshall Rooster Cogburn. (The all-star cast also included Dennis Hopper, Glen Campbell, Robert Duvall, and Strother Martin.) Into Wayne’s ten-gallon shoes steps an exceptionally crusty Bridges, whose banter with rival bounty hunter La Boeuf (a spot-on Matt Damon) and relationship with young Mattie Ross (poised newcomer Hailee Steinfeld) — who hires him to find the man who killed her father — likely won’t win the recently Oscar’d actor another statuette, but that doesn’t mean True Grit isn’t thoroughly entertaining. Josh Brolin and a barely-recognizable Barry Pepper round out a cast that’s fully committed to honoring two timeless American genres: Western and Coen. (1:50) Empire, SF Center, Shattuck, Sundance Kabuki. (Eddy)

“2011 Academy Award-Nominated Short Films, Live-Action and Animated” (Live-action, 1:50; animated, 1:25) Opera Plaza, Shattuck.

Unknown Everything is blue skies as Dr. Martin Harris (Liam Neeson) flies to Germany for a biotech conference, accompanied by lovely wife Elizabeth (January Jones in full Betty Draper mode). Landing in Berlin things quickly become grey, as he’s separated from his wife and ends up in a coma. Waking in a hospital room, Harris experiences memory loss, but like Harrison Ford he’s getting frantic with an urgent need to find his wife. Luckily she’s at the hotel. Unluckily, so is another man, who she and everyone else claims is the real Dr. Harris. What follows is a by-the-numbers thriller, with car chases and fist fights, that manages to entertain as long as the existential question is unanswered. Once it’s revealed to be a knock-off of a successful franchise, the details of Unknown‘s dated Cold War plot don’t quite make sense. On the heels of 2008’s Taken, Neeson again proves capable in action-star mode. Bruno Ganz amuses briefly as an ex-Stasi detective, but the vacant parsing by bad actress Jones, appropriate for her role on Mad Men, only frustrates here. (1:49) 1000 Van Ness, Presidio, SF Center. (Ryan Prendiville)

*We Were Here Reagan isn’t mentioned in David Weissman’s important and moving new documentary about San Francisco’s early response to the AIDS epidemic, We Were Here — although his communications director Pat Buchanan and Moral Majority leader Jerry Falwell get split-second references. We Were Here isn’t a political polemic about the lack of governmental support that greeted the onset of the disease. Nor is it a kind of cinematic And the Band Played On that exhaustively lays out all the historical and medical minutiae of HIV’s dawn. (See PBS Frontline’s engrossing 2006 The Age of AIDS for that.) And you’ll find virtually nothing about the infected world outside the United States. A satisfying 90-minute documentary couldn’t possibly cover all the aspects of AIDS, of course, even the local ones. Instead, Weissman’s film, codirected with Bill Weber, concentrates mostly on AIDS in the 1980s and tells a more personal and, in its way, more controversial story. What happened in San Francisco when gay people started mysteriously wasting away? And how did the epidemic change the people who lived through it? The tales are well told and expertly woven together, as in Weissman’s earlier doc The Cockettes. But where We Were Here really hits home is in its foregrounding of many unspoken or buried truths about AIDS. The film will affect viewers on a deep level, perhaps allowing many to weep openly about what happened for the first time. But it’s a testimony as well to the absolute craziness of life, and the strange places it can take you — if you survive it. (1:30) Castro. (Marke B.)

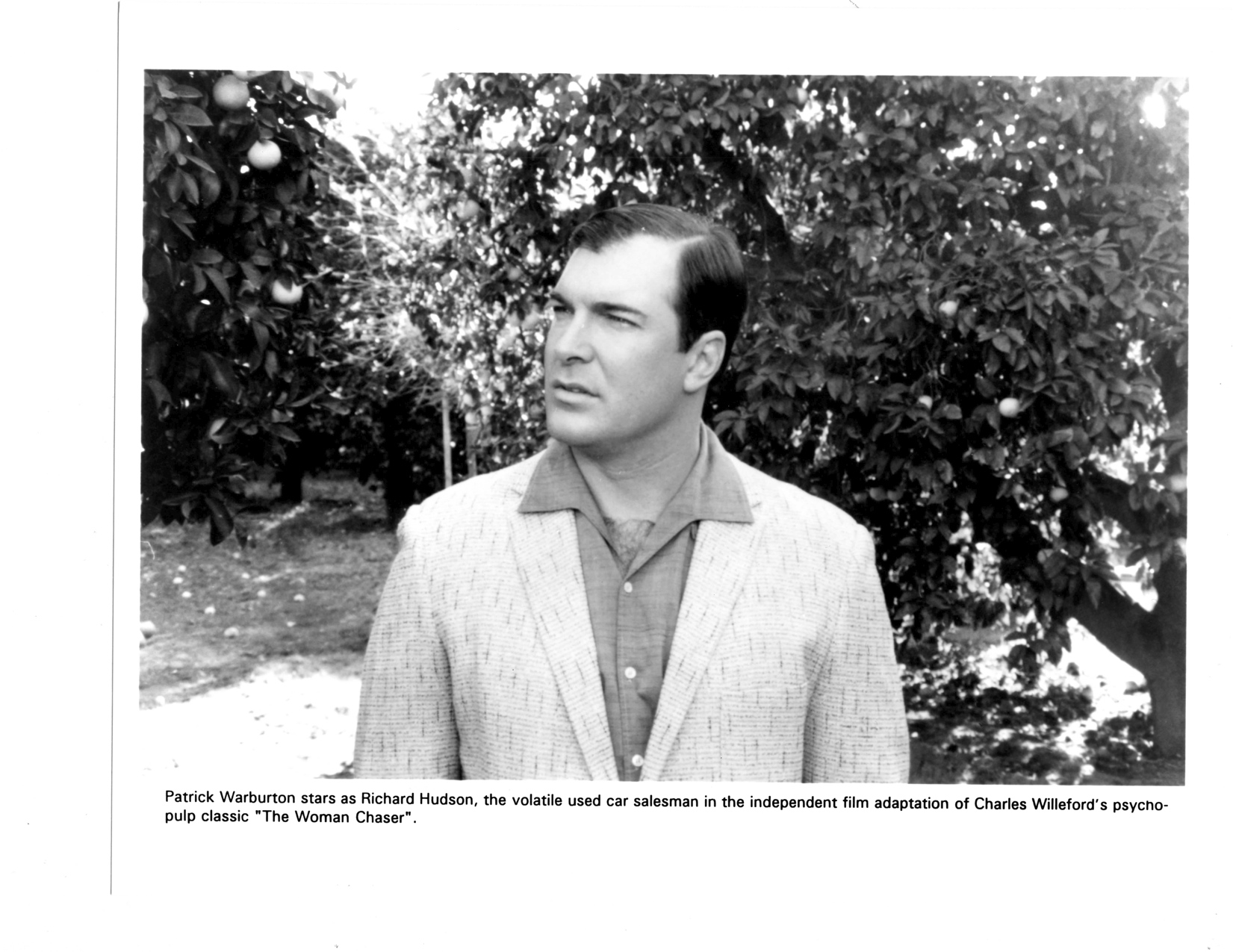

*The Woman Chaser First widely noted as Elaine’s emotionally deaf boyfriend on Seinfield, in recent years Patrick Warburton has starred in successful network sitcoms Rules of Engagement and Less than Perfect. They followed The Tick, a shortlived Fox superhero parody series everyone loved but the viewing public. He’s voiced various characters on Family Guy (a man’s gotta work), as well as endearing villain Kronk in The Emperor’s New Groove (2000). That latter reunited him with Eartha Kitt, also a co-star in his screen debut: 1987’s campsterpiece Mandingo (1975) rip-off Dragonard, which he played a race traitor Scottish hunk on an 18th century Caribbean slaving isle also populated by such punishing extroverts as boozy Oliver Reed, chesty Claudia Uddy, and creaky Pink Panther boss Herbert Lom. These days, Warburton is promoting a past project he’d rather remember: 1999’s The Woman Chaser, billed as his leading-role debut. It was definitely the first feature for Robinson Devor (2005’s Police Beat, 2007’s Zoo), one of the most stubbornly idiosyncratic and independent American directors to emerge in recent years. Derived from nihilist pulp master’s Charles Willeford 1960 novel, this perfect B&W retro-noir miniature sets Warburton’s antihero to swaggering across vintage L.A. cityscapes. Sloughing off an incestuously available mother and other bullet-bra’d she cats, his eye on one bizarre personal ambition, he’s a vintage man’s man bobbing obliviously in a sea of delicious, droll irony. (1:30) Roxie. (Harvey)

Film listings are edited by Cheryl Eddy. Reviewers are Kimberly Chun, Michelle Devereaux, Peter Galvin, Max Goldberg, Dennis Harvey, Johnny Ray Huston, Louis Peitzman, Lynn Rapoport, Ben Richardson, and Matt Sussman. For rep house showtimes, see Rep Clock. For first-run showtimes, see Movie Guide.