The 37th annual Mill Valley Film Festival opened last night and runs through October 12 at all the big Marin venues (Larkspur’s Lark Theater, Mill Valley’s Cinearts@Sequoia, and San Rafael’s Smith Rafael Film Center). Guardian critics take on the Children’s FilmFest program, docs, and offer short takes; for complete information, visit www.mvff.com.

This side of the Golden Gate, it’s a big week for Hollywood as David Fincher’s latest thriller goes up against Jason Reitman’s take on social-media malaise, as well a demonic doll and a Nicolas Cage-goes-evangelical howler (all involved in the latter better clear a shelf or two when Razzies season rolls around).

Read on for short reviews and trailers!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IVeWmLvO3sA

Abuse of Weakness Those who last saw Isabelle Huppert as a dutiful daughter in 2012’s Amour will be both thrilled and piqued to see the tables turned so remarkably in Catherine Breillat’s Abuse of Weakness. Huppert gives an unapologetic, stunning tour de force performance in what appears to be a story torn from the filmmaker’s own life, when Breillat suffered a series of strokes in the ’00s and ended up entangled in a loving and predatory friendship with con man Christophe Rocancourt. Here, moviemaker and writer Maud (Huppert) is particularly vulnerable when she meets celebrity criminal and best-selling writer Vilko (Kool Shen). She is determined to have him star in her next film, despite the protestations of friends and family, and he helps her in return — by simply helping her get around and giving her focus when half her body seems beyond her control, while his constant machinations continue to compel her. Crafting a layered, resonant response to what seems like an otherwise clear-cut case of abuse, Breillat seems to have gotten something close to one of her best films out of the sorry situation, while Huppert reminds us — with the painful precision of this intensely physical role — why she’s one of France’s finest. (1:45) Roxie. (Kimberly Chun)

Annabelle The Conjuring was a big hit last summer, thanks to its scares (the clapping game!) and its unusually thoughtful themes of motherhood, further elevated by the casting of Vera Farmiga and Lili Taylor. The one thing the story didn’t have was sequel potential — ergo, this cheapy spin-off prequel delving into the back story of a haunted doll that was only tangential to the original film’s action. Set in 1970, Annabelle begins with TV footage of the Manson murders as heavily pregnant Sharon Tate look-alike Mia — yes, just like that actress who played Rosemary! Except this actress is, weirdly, named Annabelle Wallis — stitches clothes for her impending arrival. Hubby John (bland Ward Horton) is a doctor and is never home, even going on work trips after the film’s first-act home-invasion by Satanists who curse guess-which-toy. After the baby’s born, straaaange things start to happen, and the sinister pranks become more menacing when the family moves into the gloomiest apartment building in Pasadena. As a soul-hungry demon circles closer, Annabelle hopes we’re chilled enough to ignore blatant rip-offs not just of Rosemary’s Baby (1968) but also 1979’s Amityville Horror and the ghosts of other schlocky devil flicks that’ve come before. The only thing about Annabelle that might keep you up at night: What is the otherwise respectable Alfre Woodard — cast as a confusingly motivated bookstore owner — doing in this forgettable misfire? (1:39) (Cheryl Eddy)

Art and Craft Fans of docs that can be summed up with the phrase “I can’t believe that shit really happened” are in for a treat with Art and Craft, which boasts an eccentric subject who allows filmmakers Sam Cullman, Jennifer Grausman, and Mark Becker full access yet remains entirely inscrutable. He is art forger Mark Landis, diagnosed as schizophrenic after a teenage nervous breakdown, now in his 50s, in fragile health, and living in his late mother’s Mississippi apartment. For 30-plus years, his illness has manifested in an obsession with recreating artworks with remarkable accuracy (Dr. Seuss, Picasso, you name it) — and then arranging elaborate scenarios (an inheritance, the passing of a nonexistent sister, situations that require him to dress as a priest) that involve donating the fakes (to 46 museums in 20 states, most delighted to benefit from his philanthropy). He’s not in it for the money, so the FBI merely observes his exploits, leaving the legwork to former Cleveland Art Museum employee Matt Leininger, who after realizing the deception at his own institution becomes consumed with uncovering Landis’ trail of phony brush strokes. This cat-and-mouse tale (in which the mouse is completely on his own astral plane of reality) leads up to one of the most awkward gallery openings ever captured on film — with artwork as beautifully created as it is plagiarized and deliberately misrepresented. (1:29) (Cheryl Eddy)

Brush With Danger Indonesian American stunt woman Livi Zheng wrote, directed, and stars in this action thriller about a painter who unwittingly becomes entangled with gangsters. (1:30)

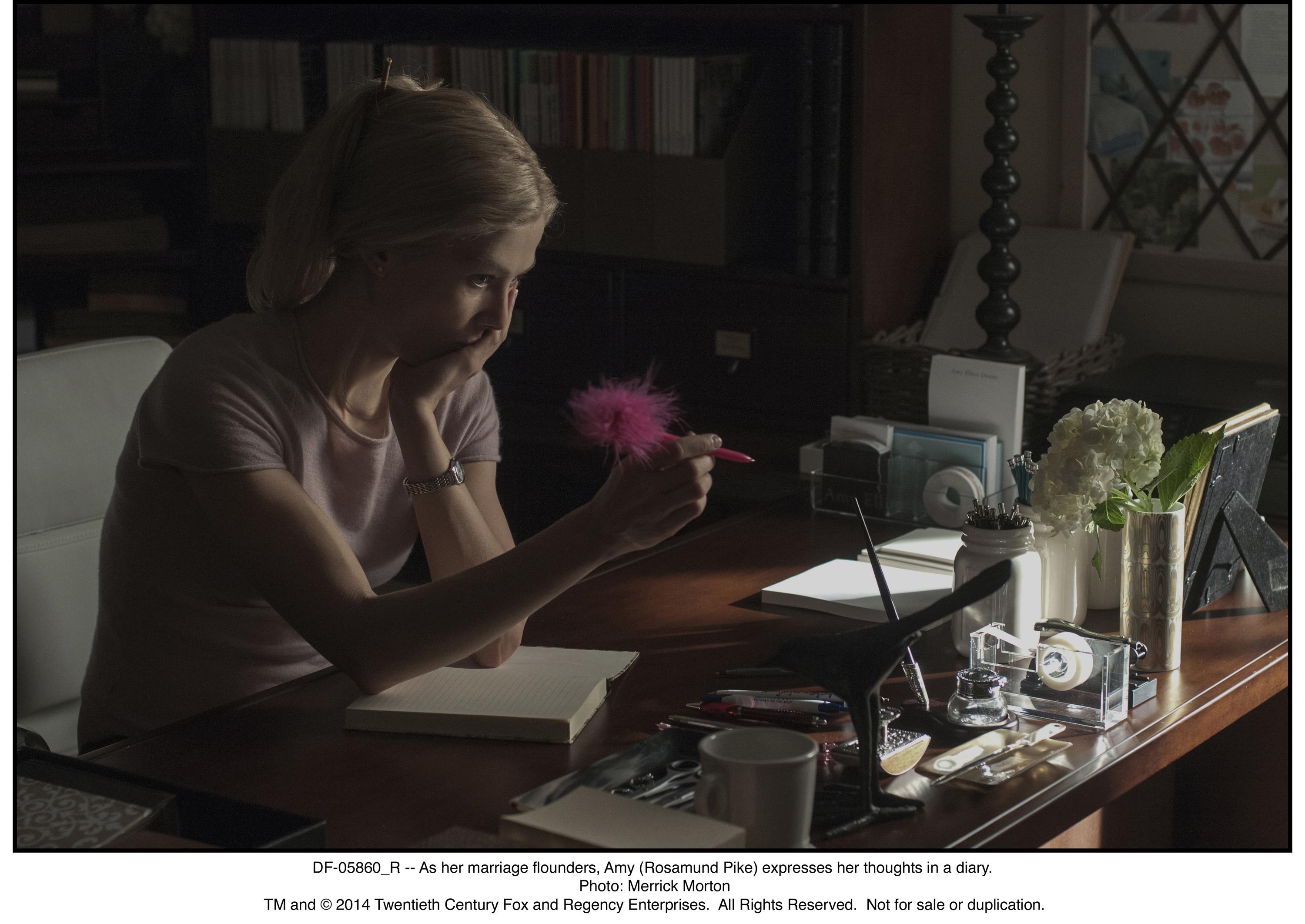

Gone Girl Gillian Flynn’s twisted 2012 tome — about a marriage about to implode at its five-year mark; the American media’s obsession with missing white women; and the wide-ranging effects of our shitty economy; not to mention a killer reminder of why the unreliable narrator is such a tasty literary device — gets the best possible big-screen scenario, with David Fincher directing (along with his usual A+ crew, including cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth and composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross), Flynn herself penning the screenplay, and an A-list cast. If Gone Girl the film comes up short in translating the book’s deliberately mind-fucking story structure, which explores the action from two distinct points of view, it succeeds in other ways, visually capturing the beige, airless, McMansions-with-overgrown-yards life of Nick (Ben Affleck) and Amy (Rosamund Pike) Dunne, forced to move to his Missouri hometown after losing their NYC writing jobs. There, they proceed to wallow in separate but mutual misery until Amy goes missing, and we get a front-row seat as the shit hits the fan in many different ways. Affleck (Flynn’s top choice) and Pike are well-cast, with Kim Dickens (as the no-nonsense detective investigating Amy’s disappearance) making the biggest impression among a large supporting cast. (2:25) (Cheryl Eddy)

Left Behind Jeepers creepers, they went and remade 2000 Christian scare flick Left Behind: The Film, based on the best-selling book series by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins. Just gonna come right out and let you know the Antichrist character does not appear in Vic Armstrong’s do-over. WEAK. But it does contain supremely awkward breakdancing; terrible CG of an airplane floundering after the Rapture makes flying a dicey prospect (apparently, air traffic control is a largely evangelical profession); erstwhile CW network heartthrob Chad Michael Murray as an internationally renowned investigative journalist (the same role Kirk Cameron played, also implausibly, in the original); and — best of all, and the only reason to seek out this ham sandwich of a movie — Nicolas Cage, who delivers possibly the worst performance of his career as an airline pilot whose sins include thinking about cheating on his born-again wife (Lea Thompson) and coveting U2 concert tickets. All of this brings up a very important question for our times: Does Jesus snark? (1:50) (Cheryl Eddy)

The Liberator Lush production values and a smoldering performance by Venezuela’s best-known acting export (Édgar Ramírez), elevate this Simón Bolívar tale from mere biopic to epic (bio-epic?) It begins amid revolutionary tumult before stepping back in time to Bolívar’s younger days; we’re brought up to speed on the tragic early deaths of his well-to-do parents, as well as the yellow-fever death of his delicate Spanish wife and some globe-trotting that allows Ramírez to show off his flawless French (he also speaks Spanish and English in the film), and for Bolívar to meet characters who prove important to his crusade for Venezuelan independence. Bombastic battle scenes and grueling marches (in and across jungles, open fields, the snowy Andes, seaside forts, blood-stained villages, etc.) soon follow, with Bolívar’s bravery and rousing speechmaking (“Freeeedooommm!”) inspiring people across northern South America and beyond, from every class and race, to join his cause. If this two-hour film feels a bit tight for such a sprawling story — especially when you consider that Ramírez’s breakout role came with 2010 miniseries Carlos, which lavished five-and-a-half hours on the career of Carlos the Jackal — it still makes for stirring viewing. (1:59) (Cheryl Eddy)

Men, Women & Children The web of title characters in Jason Reitman’s new film, set in a nonspecific-feeling Austin, Tex., stand in for a larger culture, digital native and immigrant alike, leading a significant portion of their lives online. A mother (Jennifer Garner) obsessed with the invidious snares of the scrolling feed, feverishly tracks the digital micro-movements of her teenage daughter (Kaitlyn Dever of 2013’s Short Term 12), sabotaging the latter’s burgeoning relationship with a sweetly troubled, Carl Sagan-quoting ex-football player (The Fault in Our Stars’ Ansel Elgort). Another mother (Judy Greer) embraces the seedier aspects of the mercantile web, bolstering her daughter’s dreams of stardom by pimping out her image to private customers. A man (Adam Sandler) and a woman (Rosemarie DeWitt) drift unconnected through their marriage and seek recourse among web escorts and a dating site for cheaters. The message, underscored with motifs running thickly through the interconnected plot lines, is that our lives and relationships are echoed and overlapped by a ghostly online population, whom our loved ones experience, if they notice, only as a zoned-out absence, a silent withdrawal from the room. Reitman (2009’s Up in the Air), who co-wrote the film with Erin Cressida Wilson (2002’s Secretary), finds a wealth of visual tools for mapping this populace. Texts and Facebook messages bubble up and hover over crowd scenes in an overlay, flooding the screen with drifting commentary. At cheerleading practice, one paper-thin teenager silently backstabs another via a hailstorm of emoji. If the film doesn’t issue a fiery polemic, most of its protagonists do seem caught in a stultified daze by a succession of variously proportioned screens; the emotional payoffs, and the brutal, awkward collisions, tend to come when they look up. (1:56) (Lynn Rapoport)