Believing that they’re somehow discriminated against on the streets of San Francisco, a new political coalition of motorists, conservatives, and neighborhood NIMBYs last week [Mon/7] turned in nearly twice the signatures they need to qualify the “Restore Transportation Balance in San Francisco” initiative for the November ballot.

It’s a direct attack on the city’s voter-approved “transit-first” policies, which prioritize alternatives to the car, and efforts to reduce automobile-related pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. It would prevent expanded parking meter enforcement unless requested by a neighborhood petition, freeze parking and permit rates for five years, require representation of motorists on the SFMTA board and create a Motorists Citizens Advisory Committee within the agency, set aside SFMTA funds for more parking lot construction, and call for stronger enforcement of traffic laws against cyclists.

“I think it’s been building for a long, long, long time, but the real catalyst was the Sunday and holiday parking meters,” political consultant David Looman — the 74-year-old Bernal Heights resident who is one of three official proponents of the measure — said of the motorist anger that led to the campaign. “That’s the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Yet he also said the meetings that led to the measure began in March, after Mayor Ed Lee had already called for a repeal on charging for parking meters on Sundays. The SFMTA voted to repeal Sunday meters in April, a month before the measure was certified to begin gathering signatures — an effort paid for by tech titan Sean Parker (founder of Napster and a top investor in Facebook) and the city’s Republican Party, which kicked in $49,000 and $10,000 respectively.

But Looman fears the repeal of Sunday meters could be temporary and that a small minority of road users are dictating transportation policy in a way that unfairly discriminates against motorists.

“The bike lobby is running transportation policy in San Francisco,” Looman said, even though motorists “are the overwhelming majority and we make this society run.” He said the city needs to do more to facilitate driving “so the economy can continue to function, so people can continue to shop.”

But given that drivers already dominate the space on public roadways, often enjoying free parking on the public streets for their private automobiles, transportation activists say it’s hard to see motorists as some kind of mistreated population.

“Anyone looking at how street space is allocated in our city or at the fact that a mere 1 percent of transportation funding is focused on biking improvements knows that we have a long way to go toward creating real balance on our streets,” San Francisco Bicycle Coalition Executive Director Leah Shahum told us. “City leaders are making up for decades of lost time by rightfully investing in safe, affordable and healthy transportation options.”

“The idea that anyone who walks or cycles or takes public transit in San Francisco would agree that these are privileged modes of transportation is rather absurd,” Tom Radulovich, executive director of Livable City and an elected member of the BART board, told the Guardian.

He said this coalition is “co-opting the notion of balance to defend their privilege. They’re saying the city should continue to privilege drivers.”

But with a growing population using a system of roadways that is essentially finite, even such neoliberal groups as SPUR and the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce have long promoted the idea that continued over reliance on automobiles would create a dysfunctional transportation system.

“This balance measure would be a terrible step backward for San Francisco, and it misunderstands what makes cities work,” SPUR Executive Director Gabriel Metcalf told the Guardian.

But the revanchist approach to transportation policy in San Francisco has been on the rise in recent years, starting with protests against parking management policies in the Mission and Potrero Hill, and continuing this year with the repeal of Sunday meters.

The coalition behind this ballot measure includes some of the combatants in those battles, including the new Eastern Neighborhoods United Front (ENUF) and old Coalition of San Francisco Neighborhoods. Other supporters include former westside supervisors Quentin Kopp, Tony Hall, and John Molinari, and the city’s Republican and Libertarian party organizations.

They seem to be banking on the idea that motorists are a majority of the population and should be able to dictate transportation policy.

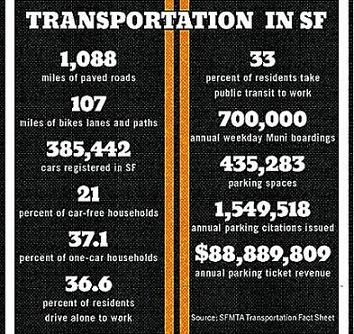

“With 79 percent of San Francisco households owning or leasing an automobile and nearly 50 percent of San Franciscans who work outside of their homes driving or carpooling to work, it is time for the Mayor, the Supervisors, and the SFMTA Board to restore a balanced transportation policy for all San Franciscans,” the group claims on its petition.

Walk SF has long advocated transportation policies that would better protect pedestrians, focused largely on trying to slow down automobiles and create safer street crossings using curb bulbouts and other tools, all of which proponents of the initiative criticize for making the streets less “efficient” for cars.

“Between bulbouts and bike lanes, the space given to cars has been drastically reduced,” Looman said.

Walk SF Executive Director Nicole Schneider told the Guardian that any effort to bring “balance” to the city’s transportation policy would help those who walk, which includes all San Franciscans at times.

“Pedestrian safety is something that accounts for 50 percent of all traffic fatalities in San Francisco and has traditionally been given 1 percent of the transportation budget,” Schneider said.

While some city officials have embraced pedestrian safety after a recent record 20 pedestrians were killed by cars in San Francisco last year, joining New York City with Vision Zero goals that seek to eliminate pedestrian fatalities, that program still hasn’t been fully funded.

Schneider said that addressing pedestrian safety means slowing down cars, citing studies showing that the chance of a collision causing a death increases exponentially with a vehicle’s speed: “There is a direct connection between slowing down traffic and reducing all deaths.”

But the initiative criticizes the “increased travel time for motorists” and calls for this official city policy: “Any proposed re-engineering of traffic flows in the City should aim to achieve safer, smoother-flowing streets.”

It’s hard to see how the initiative does anything to create “safer” streets, particularly when one listens to the rhetoric and standards of proponents of the measure.

For example, Looman considers Valencia Street to be “a disaster” after taking away a car lane to create bike lanes more than a decade ago. Yet many cyclists and city officials see Valencia as a well-functioning transportation corridor, with its “Green Wave” timed stoplights that allow both bikes and cars not to get caught in any red lights if they travel at 13 mph. Obviously, good transportation policy is a matter of perspective.

“Any city that has a Costco has to make substantial accommodation for automobiles. It’s not realistic for this to be a transit and bike town,” Looman told us, calling for the city to cater more to shoppers, families, and others that he says need to drive.

But Metcalf said it’s not realistic for San Francisco to continue catering primarily to automobiles in its transportation policy, which was the approach adopted in the bland and environmentally unsustainable suburbs that simply doesn’t work in big cities.

“Cities are crowded, diverse, and messy. There is not a great city in the world where it is easy to park,” Metcalf said. “What we need to be doing is ramping up our investments in transit, walking, and biking, not ramping it down. We need to be moving toward a city where there is less driving.”

At its core, the initiative calls for a revanchist approach to transportation policy, conjuring up a bygone era of unfettered automobility even as the number of residents and workers using the finite street grid increases substantially.

Asked what he’d like to see in transportation policy for San Francisco, Looman told us, “Let’s go back 10 years, before the proliferation of bike lanes and increased parking fees.”

“Prioritization of the single modes of transportation isn’t a matter of ideology, it’s a matter of geometry,” counters Radulovich. “We’re all better off, including motorists, if we prioritize other modes of transportation and encourage people to get out of their cars.”

Yet many San Franciscans resent being told there are limits to how much transportation policy can prioritize free parking and fast-moving streets. Radulovich said that while conservatives are driving this coalition, anger over the city’s transportation policies is based more on a sense of entitlement than conservative principles (for example, the SF Park program criticized by the coalition uses market-based pricing to better manage street parking and encourage turnover in high-demand areas).

As Radulovich said, “There are certain people who believe in the welfare state, but only for cars and not for humans.”