Not many plays feature an all-Latino cast, let alone all El Salvadoran. But Paul Flores’ Placas placed brown actors and a brown experience center stage. The 2012 production explored a father and ex-gang member’s struggle, leading his son out of a hard life of drugs, violence, and perhaps death.

The play garnered favorable but mixed reviews from critics, but among Salvadorans, it was a huge hit.

“You had older generations coming to see the play right alongside their grandkids,” Flores told the Guardian. The play’s premiere venue packed its 500-seat capacity, and sold out seven out of its eight nights in San Francisco. “We tapped a community thirsty to hear its stories told.”

Placas is the kind of creative work not being funded often enough by the city’s largest arts grant organization, critics are saying. At a contentious San Francisco Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Committee hearing on June 20, artists told supervisors that programs serving diverse communities were severely underfunded, and alleged the city’s major arts funder, Grants for the Arts, awards money disproportionately to art forms favored by white audiences.

Spurred by public outcry and city studies, Sups. Eric Mar and London Breed recommended the transfer of $400,000 in unused funding from GFTA to another city arts funder, the Cultural Equity Grants (which funded Placas), to direct arts money to people of color.

The transfer won’t be approved until it goes before the full Board of Supervisors next month. But as San Francisco studio and housing rents soar, Mar said this was vital to keeping diverse artists in the city.

“I think the crisis for arts groups now is many of them are being displaced,” he told the Guardian. “How can the city subsidize groups with low rent or free rent, and how could we support small groups [to prevent them from] being displaced?”

"Arts inequity": San Francisco Budget and Legislative Analyst Report by Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez

Above is a PDF of the Budget Legislative Analyst’s report, as it breaks down lack of funding to diverse programs. The report has relevant sections highlighted.

The Guardian reached out to City Administrator Naomi Kelly for comment (her office ultimately directs arts grants funding). She was unavailable for an interview before we went to press, but her spokesperson Bill Barnes told us, “I don’t think we should be in a position of having governments regulate artistic content.”

But in a way, the government already does. The GFTA funding is made up of city dollars, and for decades its funding priorities have scarcely changed, favoring many of the largest mainstream organizations.

GFTA funds many arts organizations, but a recent report by the Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office found it awarded about 70 percent of grants to organizations with mostly white artists who mostly cater to white audiences. The San Francisco Symphony, San Francisco Ballet, San Francisco Opera, City Arts, the Exploratorium, the Museum of Modern Art, and the American Conservatory Theater received over one-third of GFTA funding over the past five years, the report found.

“The Bay [Area] will soon be 70 percent people of color,” Andrew Wood, director of the SF International Arts Festival, told the Guardian. “Why invest so heavily in organizations that are such a minority of the population?”

Taken on its face, the findings show a stark divide between funding for smaller, struggling minority arts groups and large, independently funded arts groups with predominantly white patrons. The report divided the diversity of GFTA arts funding into three categories: people of color (Asians, African Americans, and Latinos), ethnic minorities (Arab/Middle Eastern/Jewish), and LGBT organizations. The funding for these categories remained steady at about 20, 2, and 5 percent of arts funding, respectively, since 1989.

The lack of funding is one thing, but critics say the pattern indicates an outright dismissal of the broader community. In a mass email entitled “The State of the Arts in San Francisco” sent to the arts community from a group calling itself Arts Town Hall Organizing Committee said the outcry against critiques of GFTA’s diversity funding was “advanced by fringe members of the arts community.”

Realizing it called Black, Asian, and Latino artists a “fringe community,” the San Francisco Arts Alliance (a signatory to the email comprised of San Francisco’s symphony, opera, and other GFTA funded organizations) quickly backpedaled. It said the email was sent on their behalf by the public relations firm Barnes Mosher Whitehurst Lauter & Partners, a group that often runs astroturf campaigns for mainstream organizations.

One reason for GFTA’s inability to fund diverse arts groups may be a lack of trying: The BLA found the GFTA “does not have a definition or criteria for granting funds to people of color organizations.”

This color blindness is a problem, Wood told us. “[The money] the city invests in the War Memorial Opera House compared to the Bayview Opera House, also city owned, is completely out of whack,” he said. The Bayview Opera House was one among six “cultural institutions” to receive a portion of a $400,000 GFTA award, according to the organization’s 2013/14 annual report. Conversely, GFTA awarded the San Francisco Opera $653,000 the same year.

“They’re two different universes,” Wood said.

Allocating more funding for the Cultural Equity Grants was an oft-mentioned method for better supporting disadvantaged artists, the report found, even though GFTA and CEG share many of the same grantees.

Some say the report’s numbers don’t add up. San Francisco Arts Commission Director of Cultural Affairs Tom DeCaigny, a longtime local artist, disagreed with how the BLA defined which groups were white, ethnic, or otherwise.

“The methodology in the report assigns people an identity, and I know some of our grantees were referred to as white when they’re not,” DeCaigny told the Guardian. “We would want to see organizations self identify.”

Those faults undermine the value of the BLA’s findings, although he said, “I’m hesitant to comment on the value of that report.”

But some in the arts community felt DeCaigny’s opinion aligns suspiciously closely to the mayor’s priorities: funding the preferred arts organizations of his wealthy donors (like the symphony). We reached out to the San Francisco Symphony for comment but its representatives told us it would be unable to respond before our deadline.

DeCaigny defended the symphony, noting its annual Lunar New Year and Day of the Dead concerts serve diverse audiences. For the economically disadvantaged, he said, the symphony offers free concerts open to the public in Dolores Park, and that the symphony’s “artists are very diverse.”

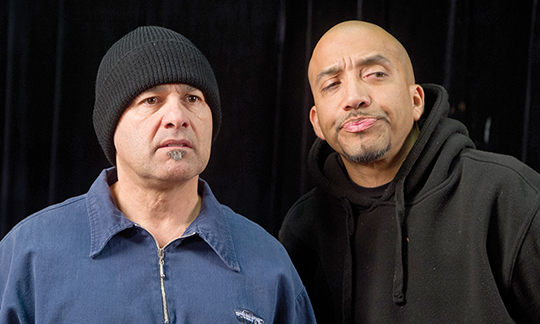

DeCaigny pointed out the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra’s youth programs (shown above) are notably very diverse.

The donors are mostly white, he said, “but that’s true in other sectors as well. It has more to do with how wealth is distributed in our society.”

But Flores, Placas’ director, explained the need for ethnically diverse art was not just about who consumes it, but what message the art is sending to the audience. Nothing revealed this more, he said, then when he took Placas on tour across the United States. While in New York City, he conducted an informal poll.

“I asked ‘when I say San Francisco, what do you think of?’ They said the 49ers, the San Francisco Giants, the Golden Gate Bridge. They didn’t think gangs, pupusa, cumbia,” he said. That’s why Placas, which told the story of gang life among San Francisco Salvadorans, had such impact in the city and even beyond its borders.

“I love telling stories about San Francisco,” Flores told us. “The symphony doesn’t do that, the opera doesn’t do that. What does that? Locally generated art.”

The Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance committee is tentatively slated to hold a hearing on allegations made in the BLA report on July 16.

Jasper Scherer contributed to this report.