San Francisco’s municipal transportation system stood still, stranding middle class riders. Riots raged throughout the city as over 1,500 streetcar drivers, known as carmen, literally fought with bottles and stones for higher wages. Left with few options, stranded San Franciscans took to other means to get to work: by foot, by bicycle, and by horse-drawn carriage.

The year was 1907, and United Railroads carmen raged against their Baltimore-based bosses in a year-long strike, in the wake of the great earthquake and fires that leveled much of the city of St. Francis. It was a clash that made last week’s Muni driver sickout look tepid and tame by comparison.

It was one of the single bloodiest strikes in San Francisco history,” Fred Glass, a California labor history teacher at City College of San Francisco, told us. “People were killed on both sides as the cars were run by armies of scabs.”

But minus the violence, the century-old union action has eerie parallels to last week’s Muni sickout, the “non-strike” in which nearly 500 Muni drivers left buses stagnant in garages across San Francisco. The similarities begin with anti-union sentiment in the mainstream press.

As the conservative-leaning San Francisco Chronicle did during this sickout, one of the city’s papers-of-record, The Call, lambasted the unions and city officials alike in 1907.

“Two of the most essential public utilities, the streetcar monopoly and the telephone monopoly, are tied up,” The Call wrote in a front-page editorial on May 06, 1907. “Where — and the question must suggest itself irresistibly to every man with a spoonful of brains — where does the public get off?”

A mob of strikers circle a streetcar at Turk and Fillmore, one site of violence during the 1907 carmen’s strike. San Francisco Examiner file photo courtesy of Market Street Railway, home of lots of interesting SF public transportation history.

The Call offered to publish the tirades of everyday citizens. Today, we can hear the hew and cry more directly. Last week, #MuniSickOut was a top San Francisco trending Twitter hashtag, as irate tweeters pounded their thumbs on smartphones with thoughts like that of user @ReggieMuth: “Grind the city to a halt? You should pay the consequences.”

Muth’s sentiment was echoed by many on the Twitterverse, and angry citizens emailed city leaders as well. One constituent wrote to Sup. David Chiu’s office that, “Public transportation workers held the public hostage for their greedy demand on pay and benefits.”

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency proposed Muni workers pay into their pensions more than it was offering in salary increases, amounting to a pay cut of $1.10 per hour. Muni workers make on average $29.52 an hour, the sixth-highest paid transit workers in the nation, according to the SFMTA. But San Francisco also has the highest cost-of-living in the country.

Transit Workers Union Local 250-A President Eric Williams told us most Muni drivers were long ago priced out of living in San Francisco. “The only members that live inside the city are those who purchased a home 20 or so years ago,” he told us. “The majority of our members live outside the city.”

Muni workers’ wages used to be mandated to be the second-highest in the nation. But in 2010 voters passed Proposition G, requiring Muni worker wages be negotiated and subjected to binding arbitration that the union says is skewed in the city’s favor. But Prop. G and the city charter also prevents workers from striking, hence the drivers calling in sick en masse.

By modern standards the Muni sickout was labeled extreme, by the Chronicle and others. San Franciscans of 1907 feared the URR carmen’s strike for another reason: The workers were ready to die for their cause. Market Street Railway and issues of The Call recalled the strike christened on a day known as Bloody Tuesday.

On May 07, 1907, a mob of URR carmen formed outside the Turk and Fillmore carbarn. At 3:25pm, six streetcars emerged, greeted by a hail of sticks and stones from the strikers. The cars were driven by scabs who crossed the picket lines. More dangerously, they were also manned by gunmen at the behest of the infamous URR strikebreaker, James Farley.

A second pelting of sticks and stones drew action: Farley and his men opened fire on the crowd. Bullets sprayed wildly into nearby police and union men alike. The strikers ran for cover and fired back. A gun battle echoed past what is now a Bi-Rite grocery, ending only when the strikers lacked the ammo to carry on.

“CAR STRIKE LEADS TO BLOOD” read The Call’s headline on Wednesday, May 08, 1907. The first to die was 19-year-old James Walsh, a teamster who was shot through the head. Ultimately, two died and 20 were injured that day. The strikers would bear six fatalities by 1908.

BLOODY TUESDAY "The Call" — May 08 by Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez

San Francisco is not only experiencing transit strike deja vu, but a repeat of the economic circumstances around the historical Bloody Tuesday, with a wealth gap approaching historic highs. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2012 the top 1 percent of Americans took home about 22 percent of the nation’s wealth, and the bottom 90 percent of the country took home less than 50 percent of the nation’s wealth.

A look at a graph of income inequality shows two giant spikes of the 1 percent’s massive wealth, one spire in the modern era, and another spire planted firmly in the gilded era of the early 1900s, altered only by the Great Depression and the leveling economic policies adopted to address it.

“We’re back to the level of inequality that existed at that time now,” Glass said. “To me that suggests there’s the potential for that kind of explosive conflict between classes.”

The 1907 strike was one in a series of labor battles around the country as wealth became consolidated in fewer and fewer hands, peaking with the stock market crash of 1929, after which the continuing hard times led to one of the most famous union actions in San Francisco history: The Longshoreman’s Strike of 1934.

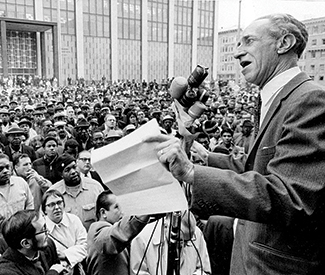

Led by Australian-born Harry Bridges, the Longshoreman’s Strike seized San Francisco even more boldly than on Bloody Tuesday, with other unions participating in a General Strike that paralyzed the city. That and other labor battles compelled Congress to adopt the National Labor Relations Act, cementing union power that strengthened the middle class, which is today disappearing.

Harry Bridges’ brought the city of San Francisco to a standstill.

“It’s poor or rich in this city,” TWU’s Willliams told us. “There’s no in between, that’s no secret.”

But worse than just a hollowing out of San Francisco’s middle class, modern workers teeter on the edge. Creatives, designers, tech employees, and other professionals are increasingly independent contractors, “freelancers” with little wage or job security protections. Many tech workers, notably younger and libertarian-leaning, also may have little experience with unions, Glass said.

The difference in sentiment between the 1900s and now may be that of will. Glass tells a story from one of his History of California Labor classes. The year was 1991, and as is usual with most community colleges, Glass’ class drew people of a wide range of ages.

“One of my students was a woman in her late 70s,” he recalled, “and she listened as I talked about the situation before the Longshoreman’s Strike. I mentioned some people were disappearing, people lost their jobs, there was a dark mood, even suicides. She stopped me right there.”

“She said ‘I was there, and what you’re saying is completely wrong. Sure, some people despaired, but when we organized, we had hope.You want to know about despair? Now is the real despair, because people don’t think they can change anything.'”