Former Mayor Willie Brown was infamous for keeping the workings of San Francisco government secret. Now his successor, Mayor Ed Lee, has codified government secrecy into written policy.

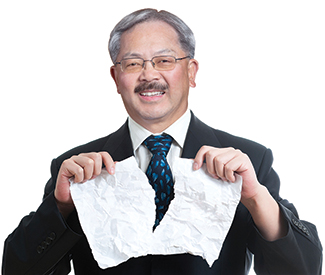

A Bay Guardian review of Lee’s newest public records retention schedule found the mayor granted himself the ability to destroy public records with broad power: deleting emails deemed “routine,” drafts of legislation, and records of telephone calls to the office of the mayor.

The policy should have anyone interested in government transparency up in arms. It potentially flouts the California Public Records Act, as well as the city’s Sunshine Ordinance, state and local laws granting citizens and journalists alike the legal right to keep tabs on what goes on under the hood of the political machine.

Emails, which Lee’s policy says the Mayor’s Office can destroy, are a particularly powerful tool for keeping government in check.

“Sources can be less than reliable, but an email speaks for itself,” said James Wheaton, senior counsel for the First Amendment Project, a group that defends the public’s right to government information. “Emails are a unique window into the way an institution functions. We call these things ‘paper trails.'”

But the paper trail used to track the mayor is kept in the shadows by his new policy, the most recent crack to appear in an eroding wall of public trust in open government.

LET THE SUNSHINE IN

Reporters and engaged citizens depend on access to public records to do the everyday dirty work of keeping an eye on government.

In 2010, reporters from the Los Angeles Times investigated the town of Bell’s corrupt network of city officials (including the mayor and police chief), who swindled money from city coffers. Public record requests of their emails revealed brazen exchanges: “I am looking forward to seeing you and taking all of Bell’s money?!”

Closer to home, public records allowed a Sacramento Bee investigative reporter to uncover perilous corrosion in the new eastern span of the Bay Bridge, leading to a public outcry over a threat to public safety.

The Guardian, long critical of mayoral backdoor deals, often requests emails from government agencies to track people in power. “Behind the Tweets [3/11],” relied on emails obtained from the Mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development to chronicle how Twitter wrangled local lawmakers into weakening the benefits it had to supply the city in exchange for its much-contested tax breaks.

A recent Guardian investigation led us to the mayor’s newly minted policy. When Guardian Editor in Chief Steven T. Jones requested email correspondence from the Mayor’s Office, we were told the emails may have been deleted, leading us to ask a reasonable question.

“What the hell?!”

VANISHING PAPER TRAIL

On April 22, the Guardian made a Sunshine Ordinance request to the Mayor’s Office for communications involving Tenderloin power broker Randy Shaw and the Tenderloin Museum project that he and Lee launched at a press conference the previous day.

A week later we obtained two emails from Shaw copied to city government officials: one supporting Ellis Act reform, and another calling for a city crackdown on the Turk and Leavenworth Smoke Shop.

We spoke to Kirsten Macaulay, who handles Sunshine requests for the Mayor’s Office, and asked about something quite curious: Even though Lee and his office were involved in a press event with Shaw on April 21, there were no emails or other messages setting up that event or coordinating when the mayor would speak.

We asked where those emails were, and got an astounding answer: They may have been deleted, she said, a regular practice for emails deemed to be “routine.”

“We don’t have a record retention policy against deleting emails,” she said.

That seemed to explain a number of suspicious responses to routine records requests we’ve made after politically charged decisions.

After a controversial behind-closed-doors political move by power broker (and Lee ally) Rose Pak to replace progressive Police Commissioner Angela Chan with a former Ed Lee campaigner, Victor Hwang, the Guardian requested emails from the mayor’s office concerning either candidate.

“This office is confirming that we do not have any responsive documents,” Macaulay wrote in reply to our request.

When we made similar requests of city supervisors, we received more than 70 emails per supervisor, supporting and decrying both candidates. The emails were like a trail of bread crumbs leading back to power broker Pak, revealing all the community members who had stepped in as proxies on her behalf to flex political muscles.

No such luck with the mayor.

The idea that not a single soul would send an email to Lee, nor would he or his staffers send a single email regarding the appointment of Chan, or of her opponent, just isn’t credible.

The Guardian pushed on the issue and obtained a copy of the records retention policy from the Mayor’s Office. The Mayor’s Office drafted a new version of that policy, which was quietly approved by Lee’s Chief-of-Staff Steve Kawa as well as City Attorney Dennis Herrera in February.

We’ve been pushing for more information on how that policy differs from previous versions, and whether it complies with state and local public records laws. But the staff member from Herrera’s office who dealt with the policy was unavailable for comment, and we haven’t gotten a straight answer from the mayor himself.

“San Francisco has the strongest open government and sunshine laws in the country,” Christine Falvey, a spokesperson for the mayor, told us. “The Mayor’s office fully complies with the spirit and letter of the law.”

She would not grant us a direct interview with the mayor. When the Guardian asked the mayor if he has the legal right to delete his emails when we saw him outside a campaign party Tuesday night, he said “I’ll answer your questions later,” and shut his car door in front of us.

One thing is for sure: The new policy has holes big enough to drive a Mack truck through, and that has open government advocates worried.

POLICY EXPERTS WEIGH IN

The most troubling language in the mayor’s new “Records and Document Retention and Disposal Schedule,” as it’s formally called, can be found on page two under the heading “No Retention Required.”

This section details which documents the Mayor’s Office believes it may destroy.

“Documents and other materials (including originals and duplicates) that are not required for retention, are not necessary to the functioning or continuity of the Department and which have no legal significance may be destroyed when no longer needed,” the section states. “Specific examples include telephone message slips, notes from ongoing projects, preliminary drafts that have been superseded by subsequent versions, routine emails that do not contain information required to be retained under this policy, miscellaneous correspondence not requiring follow-up or departmental action, notepads and chronological files.”

Emphasis ours. Attorneys we spoke with were concerned the exemptions would keep the public in the dark.

“The city should be retaining all records that bear on the operations of government and public oversight thereof,” David Greene, senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation told us. “The listing of telephone message slips — which sometimes might be the only record of a communication — is a disturbing example. Same for ‘routine emails’ — whatever that means.”

Terry Francke, lead counsel at open government group Californians Aware, went further, saying the records the Mayor’s Office claims it can destroy flouts state law.

“State law,” he said, “sets a minimum retention period of two years for any records of a city or county.”

We asked, does that mean any records destroyed in under two years would run afoul of state retention policies?

“Other than duplicates,” he said, “yes.”

He pointed to California Government Code 34090, which states cities cannot destroy records affecting the title to real property, court records, and records required to be kept by statute. Importantly, cities also cannot destroy records that are less than two years old.

Contrary to that law, emails the Mayor’s Office said may have been deleted were less than a few months old.

Rick Knee, a longtime member of the city’s Sunshine Ordinance Task Force, was cautious.

Alarmingly, he said, “the list of documents of which retention is not required allows the destruction of records that should remain open to public scrutiny, and gives the mayor’s office far too much discretion to decide what is or is not ‘necessary to the functioning or continuity of the department.'”

The Sunshine Ordinance Task Force is the only city body specifically tasked with enforcing government transparency laws, which are in place to ensure that government conduct remains open to public scrutiny. But the power of that entity to act effectively is under threat, as city supervisors recently rejected two strong new appointments from the Society of Professional Journalists, one of whom litigated against the federal government to obtain public records regarding the National Security Agency, domestic drones, and more.

San Francisco politicians interested in deleting documents wouldn’t benefit from strong government watchdogs on the task force.

We can only hope local open government advocates and journalists alike will challenge the mayor’s policy, which potentially flouts state and local open government laws. But that may not be enough.

Even if we had ironclad rules safeguarding government email, Wheaton, an attorney with the First Amendment Project, pointed out there are ways around transparency.

Two months ago, the California Court of Appeals ruled in City of San Jose v. Superior Court (Smith) that personal emails and text messages of government officials are not public record.

“It’s just handing every corrupt politician an absolute get out of jail free card,” Wheaton said. “Now all they have to do is get a Gmail account to stay out of the public eye.”

Or, corrupt politicians could take the route of Mayor Brown, who barred digital devices in his presence during staff meetings and famously does not use email.

In his column for the San Francisco Chronicle, Willie’s World, Brown explained his position on email to former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“These days, Schwarzenegger appears to be more into tech than politics. Do I do Twitter? he eagerly asked me. Do I do e-mail?

‘No, no, no,’ I said. ‘Let me remind you of something, governor. Do you know what that ‘E’ in e-mail stands for?

‘No.’

‘Evidence.‘”

Steven T. Jones contributed to this report.

UPDATE: The Bay Guardian was given a brief quote by Christine Falvey, the mayor’s spokesperson, for this story on Monday. Though we used the quote in the print version of this story, an error on our part led to it not being included in the web posting. We have corrected the web posting and apologize for the error.

Below we’ve embedded the document retention policy for download and viewing.

San Francisco Mayor's Office Record Retention Policy 3.7.14 by Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez