arts@sfbg.com

THEATER It got cold only once last week in Austin, and that was in the refrigerated beer grotto at the Whole Foods. Otherwise the famously incongruous Texas capital was a sultry pleasure. Arriving midway through the 12-day Fusebox festival (April 16–27) allowed for a concentrated dose of Austin’s relaxed mien and fervent tastes, as I took in a slab of what Fusebox’s organizers refer to as Free Range Art. Among other things, that meant a program that roamed widely over categories and disciplines as well as points of origin: The festival annually culls its performance-based, visual, conceptual, and food-related projects from local, national, and international artists in roughly equal proportion.

The Bay Area was represented this year by a rousing episode of choreographer Larry/Laura Arrington’s highly collaborative experimental “game show,” SQUART! (co-produced at Fusebox by Austin-based House of Ia), which had a far-flung mix of local and guest artists putting out completed (often complex and impressive) performances in a matter of a few hours. SQUART! also featured on its luminous panel of celebrity judges the likes of postmodern dance icon Deborah Hay (who by way of one critique led the crowded barroom venue in a chorus of “Don’t Fence Me In”). Another intimidatingly dazzling celebrity judge was Christeene, Austin actor Paul Soileau’s fierce and brilliant drag alter ego, who would go on to close out the festival on Saturday night with an all-new, ferocious floor show.

Underscoring the Free Range theme in the festival’s second week were several remarkable performances that straddled the line between visual art, installation, and conventional theater.

One of these was 33 rpm and a few seconds, by renowned Lebanese theater artists Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh, whose stage comes littered with several past decades worth of communication technology — including the turntable alluded to by the title as well as a fax machine, an answering machine, a cell phone, and stacks of books, all backed by an enormous projection of the principal character’s Facebook wall. Notably, the stage remains devoid of any actor (other than a voice heard on the answering machine). Also notably, the principal character, based on an artist and activist in Beirut, is already dead. Only his devices and Facebook account continue to churn with life, as a host of friends, colleagues, and strangers remotely discuss, deliberate over, and variously appropriate his ambiguous suicide. With pointed associations for war-scarred Lebanon’s contentious recent history, yet reverberating with a larger state of affairs, this sly and intriguing, multichannel conversation shimmers with our own ghostly and fragmented existence.

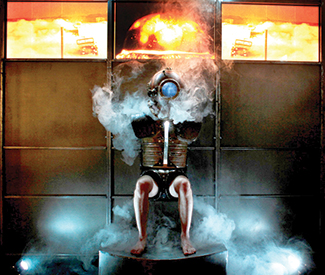

Man Ex Machina, meanwhile, had at least half an actor onstage as it delivered a brilliant and chilling multimedia treatise on the evolution of human and machine. Written, directed, and performed (in a stationary but cleverly versatile steam punk cyborg suit with two bare legs poking through) by multifaceted Bulgarian artist Venelin Shurelov of SubHuman Theatre, this riveting “cyber lecture” unfolds as a combination video game, animated documentary (the stunning 3D animations are by Yosif Bozhilov), and post-human minimalist cabaret. Its alternately grim and bracing vision of human evolution comes leavened by a tender humor, but packs enough punch in its trim 50 minutes to leave your head swimming.

Los Angeles–based multimedia artist Miwa Matrayek had two exquisite, visually and musically lush works in this year’s festival, Myth and Infrastructure and This World Made Itself. Both feature her astounding multi-projection animations, into which she folds her own 2D shadow-screen persona in real time. Disappearing into this layered screen world, her shadow becomes traveler and witness to the great and ominous unfolding of human action in the natural world. Indeed, This World Made Itself in particular proved a forceful complement to Man Ex Machina as it pondered the evolutionary timeline of earth, human agency, and the fragility of life in its own distinctive aesthetic and emotional register.

Beyond the merits of any single work, what remains so impressive about the festival’s diverse offerings (and artistic director Ron Berry’s shrewd curatorial vision) is the way the pieces so often spoke to one another. These unpredictable resonances emerged organically for the most part, but together with infusions of the featured Paloma Mezcal punch they fueled a subtle expansion of thought and feeling in a laidback setting devoid of any preciousness.

Free Range meant one more thing at this year’s Fusebox: For the first time in this modest-sized but distinguished festival’s 10-year history, all tickets to all shows were free to the public. The festival’s organizers say they hope that by eliminating the ticket price — while still programming leading and challenging work — Fusebox will spur a deeper conversation about value, rather than continue to mask it behind the narrow and misleading idea that the ticket price is the end of the story (in reality, ticket prices rarely even come close to covering the actual material cost of producing such work).

Whatever else, the free ticket seemed to at least eliminate the mundane anxiety that comes with unfolding your wallet and deciding whether a purchase is worthwhile. Getting rid of that consumer judgment may also be enough to subtly but productively change the terms of relation between the public and the artist. If that’s a hard thing to measure, it was easy enough to detect in the amiable mixing that went on throughout the festival. And who knows, it’s possible too that a “free range” opens up a mental and social environment in which the real value and import of much of this work — whether delivered through the taste buds by high-concept gelato or reflected in the miraculously beautiful, agonized mirrors of Matreyek’s animated sets — can be transmitted to us all with less distortion from the ideological frequencies of a market-driven society. *