Historic new protections are now in place for children facing police action in the San Francisco Unified School District.

Reforms include having a parent present when police question a child, tracking police presence in schools, and using a more lenient approach than simply dragging kids off to the police station or juvenile hall. All of these may be strengthened by a new memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the SFUSD and SFPD.

The MOU, passed by the Board of Education at its Feb. 25 meeting, places new restraints on police officers when they come into schools, with specific outlines for when schools should call police, board President Sandra Lee Fewer told the Guardian.

“It’s about changing student behavior, versus punishment,” she said. The agreement dovetails with the district’s new restorative practices initiative aimed to decrease reliance on suspensions to correct behavioral problems (see “Suspending judgment,” 12/3/13).

All sides say the MOU is strong, but one section was weakened shortly before it was voted on. In the final hour before the MOU was brought before the Board of Education, the police revised the language of the agreement.

One important word was changed in a section describing how police are to respond to student crime on school grounds: a “shall” became a “should.” Critics say that change transforms the contract from a legally binding agreement signed in goodwill to a mere suggestion of cooperation from the police.

“To a civilian, those are everyday words. To a police officer, they’re the difference between always and never,” Police Chief Greg Suhr told the Guardian.

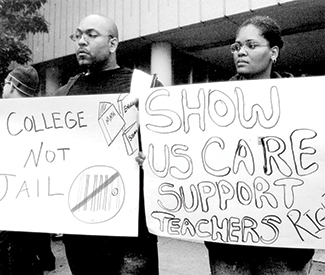

At a Jan. 14 Board of Education meeting, members of Coleman Advocates for Children and Youth told the board that this contract was no mere suggestion: It is vital to the safety of children.

Kevine Boggess of Coleman Advocates worked on the agreement for over two years, explaining to the board why “shall” was so important: “We feel like this is something that’s necessary for this document to really stand true, to make sure students are treated with respect and not introduced to the criminal justice system.”

Boggess said cops need stringent rules. But to see why those rules are necessary, we need to revisit a dark day in San Francisco history, when police discretion turned a school brawl into a riot.

MELEE PROMPTS REFORMS

To those who remember, that day in 2002 is known as 10/11. Board of Education member Kim-Shree Maufus remembers that day well.

Maufus was sitting at work when her friend, a teacher, emailed her alarming news: Maufus’ daughter was in danger. She was a sophomore at Thurgood Marshall High School, and the entire school was under attack.

Barriers blockaded the streets around Thurgood Marshall and helicopters swarmed the skies. At least 100 armored officers stormed the school, weapons at the ready.

“They were beating them. When my daughter got on the phone, I couldn’t understand her. It wasn’t English. Later, I understood it was a nervous breakdown,” Maufus told the Guardian.

The book Lockdown High recounted the incident in which Maufus’ daughter and dozens of other students, as well as teacher Anthony Peebles, were batoned by police and injured.

The San Francisco Bay View’s article on the incident quoted a student who saw the violence escalate: “‘We were coming out of the office as the fight was going on, and an officer took his gun out at one of the students and told him, ‘Don’t make me use this,’ said Ely Guolio, a student. ‘I was shocked.'”

The police allege they responded to a riot, and although four students and a teacher were arrested, all charges were later dropped, according to a San Francisco Chronicle report from 2003.

In the incident’s wake, Coleman Advocates and other groups called for change. Proposition H was passed by San Francisco voters in 2003, reforming the Police Commission to provide better civilian oversight of the SFPD.

But negotiations around an MOU between the police and the school district stalled for years. The tensions between the two bodies were high.

“Police would come to schools and arrest students, saying the students were re-igniting incidents from Thurgood Marshall,” Maufus told us. “The Thurgood Marshall melee was absolutely the catalyst to get the conversation started on how to structure police on school property.”

In 2005, an MOU was crafted, but many viewed it as ineffectual. Although this new agreement between the SFPD and SFUSD has many strong new rules, one rule was weakened that pertains to the violence of 10/11.

The section in question reads: “Subject to the exception described below, when SFPD officers make a school based arrest they should (emphasis ours) use the graduated response system outlined below.”

The graduated response system sets rules for police officers when they enter a school to make arrests for low-level offenses. It’s a “three strikes” rule: the first offense warrants admonishment or counseling, the second offense asks for the same or a diversionary program, and the third recommends a juvenile be placed in probation or a community counseling program.

“It’s definitely less binding,” Fewer told the Guardian. “But the police chief would not sign it with more binding language.”

Suhr said he doesn’t want his officers restricted in an emergency. “You can’t take all discretion away from a police officer, and expect that officer to assume liability (for the situation),” Suhr said.

Some said the SFPD of today is easier on students than 12 years ago. Juvenile arrests are down, with just over 600 felony juvenile arrests in 2012 compared to 1,100 in 2003, according to SFUSD data.

COOPERATIVE APPROACH

Implementing a restorative justice model and new standards for police in the schools isn’t just a matter for the SFPD, but for individual school administrators as well, with Fewer noting that the SFUSD sometimes calls the police for routine disciplinary matters.

The Guardian profiled one such student in “Suspending Judgment,” telling the story of a school official who called on the police to discipline a kindergartner throwing a tantrum. Suhr agreed, “You can’t have police officers enforcing school discipline.”

The MOU now seeks to address that problem in a section directing school administrators to only call the police for public safety concerns and crimes. And though the MOU is not as ironclad as advocates may have wished, there are still many wins for reformers.

One of the authors of the agreement, Public Counsel’s Statewide Education Rights Director Laura Faer, said the new mandate for data collection is one of the key sections of this MOU. Now, the SFPD will report how many times officers have entered school grounds to arrest students.

“There will be a regular dialogue with the community about arrests,” she said. “It’s extraordinary.”

The agreement also has mandates for training with the SFPD on school policies. And, as Fewer reminded the Guardian, this is a living document. All parties now have new promises to live up to.

“This is the beginning,” Faer said, “this is not the end.”