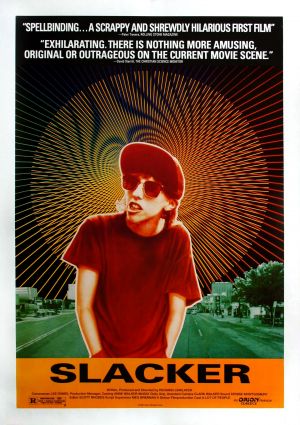

My second year of attending the Sundance Film Festival was at the age of 15; it was 1991 and I took a chance on a film called Slacker by Richard Linklater.

This is the ticket stub that started my film journals. It’s still taped into a spiral ring notebook that cradles my coming of age, and I have treasured every film of Linklater’s since: his mainstream breakthrough, cult classic Dazed and Confused (1993); his hilarious remake of The Bad News Bears (2005); his underrated adaptation of Fast Food Nation (2006); his overlooked staging of Tape (2001); his pioneering, existentialist, rotoscoped duet Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006). And, of course, his soul-searching Before trilogy.

I have consistently been amazed by his solid output and the impressive auteurism of his career. And all the while — as he kept delivering works like the unfairly dismissed Me and Orson Welles (2008) or the universally celebrated School of Rock (2004) — Mr. Richard Linklater had his magnus opus, Boyhood, stirring beneath us. Working from an idea concieved immediately after 1998’s The Newton Boys (the only Linklater film I haven’t seen!), the writer-director decided to follow a boy from the age of six to 18 in real time — following the model of Michael Apted’s Up series, which began in 1964 and has since followed the same group of children, checking in every seven years which is currently at 56 Up (2012).

Linklater cast frequent collaborator Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette as the boy’s parents, along with his own daughter Lorelei Linklater, and has filmed them all every year for the past 13 years. The excitement and anticipation I have felt for this epic journey through adolescence has been something of a personal obsession. In fact, I even questioned Linklater after the premiere of Bernie (2011) as to when this damn film was going to be completed, to which he casually responded, “Oh yeah, I should probably finish that someday.”

It’s truly wondrous to watch Boyhood‘s titular character, Ellar Coltrane, grow up right before your eyes, enhanced by masterful editing of perfectly scripted moments. The end effect is transcendent; it’s as if you are watching your own childhood, combined with the knowledge and experience of being the older characters who often make even more mistakes than the young boy. There is nothing anyone can say that will deter me from defining this film as an undisputed legendary masterpiece on par with The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather II (1974) combined.