UPDATED 5:30 PM: Guardian News Editor Rebecca Bowe filed a report from the latest NTSB press conference on the BART accident that claimed the lives of two workers in the midst of the BART strike, which can be read here.

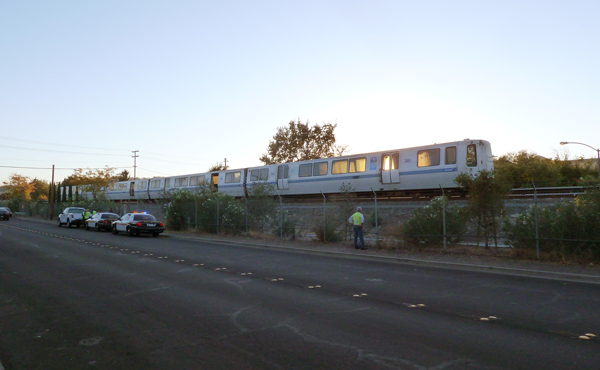

After two BART workers were struck and killed by a northbound train in Walnut Creek on Saturday, there are many questions to be answered: Why was the train moving in a district shut down by a labor strike? Were normal safety procedures being followed? And, most importantly, what could have prevented this tragedy?

Those of the some of the many questions that are now being investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board, which it said could take as long as a year to answer publicly.

That’s a year without answers. “This is going to take a long time to investigate,” Grace Crunican, BART’s general manager, said at a press conference after the accident.

The investigation won’t be conducted entirely in the dark, an investigator said. For the first few weeks the investigation will focus solely on fact gathering and be reported to the public without opinion. Jim Southworth, an NTSB investigator, hammered that home at a press conference on Sunday.

“I will not speculate,” he said, with the site of the accident just nearby.

What we do know is this: Christopher Sheppard, a BART manager and member of the AFSCME union, and Larry Daniels, a contractor, were inspecting a “dip in the rail” before they were hit by an oncoming train Saturday afternoon. There was a camera inside the train facing the cabin, but no camera facing out towards the track. The two workers were required to go through what’s called a Simple Approval process to get permission to work on the track, and the NTSB will be looking at how that and other safety rules were adhered to.

Longtime BART safety trainer Saul Almanza arrived at the scene shortly after the public was notified of the accident. He described the site of the crash as gruesome, in an interview with the Guardian. He had Sheppard and Daniels in his safety classes. He knew them. He stared downward as he recalled seeing the forms of his fellow workers under yellow sheets. Four workers have died on the job at BART before this, he said.

Drawing on his many years teaching safety to BART workers, Almanza explained what safety rules should have been adhered to when workers were out on a track.

Automated message error

BART has a brochure for workers outlining trackside safety procedures, called The Wayside Safety Program. This February 2013 manual lays out how workers signal to train operators that they’re about to work on the tracks.

Simple Approval is a process workers use to keep the Operations Control Center “aware of the presence of personnel in a specified location in the trackway,” according to the manual. When workers are preparing to work on a track, they must recite the simple approval to the Operations Control Center, also known as central control. It works like signing a waiver, saying that you understand the rules of safety, and more importantly, that you can work on the track without diverting trains.

Cars of steel can whip by at any moment, so it’s important for workers to use simple approval to signal to central control that they are prepared.

But it’s also a warning system. Once simple approval is given, train operators are supposed to be notified that someone is working on the tracks.

When central control enters that information into the computer, an automated message is relayed to all of the BART system, including trains, warning which tracks have workers in harm’s way. Alarmingly, audio from BART dispatch, obtained by journalist Matthew Keys, revealed that the automated message from central relayed that there were no workers on the tracks.

It was wrong.

Radio dispatch reveals an erroneous automated message. Audio by freelance journalist and blogger Matthew Keys.

“A message from BART operation: there are no personnel wayside,” the automated message said in a female tone (wayside means on the tracks).

Afterward, a voice piped up on dispatch to correct the automated message. “Disregard, attention all personnel, we have personnel wayside,” said the next message, this time by a human worker.

But the erroneous message could have confused the train operator, Almanza said, and possibly led to a fatal error.

A more experienced operator, like the ones BART uses every day, may have caught the subtleties in the communication, he said, but someone who was refreshing their skills might not have caught the second message. Catching shifting commands quickly is “one of the nuances” of train operations, Almanza said.

Even if the train operator wasn’t expecting the workers to be on the tracks, there were still measures in place to ensure their safety. One of these is the 15-second-rule, and there’s a chance this process could have saved their lives if it had been observed.

15 second rule

BART’s safety policies outline that if an inspector working on the track obtains simple approval, they must adhere to the 15-second-rule. Basically, a worker can’t work somewhere on the track from which they can’t see a train coming 15 seconds away — like around a curve, elevation, or track shrouded by vegetation. If they need to work in a section of track with less visibility, they have to follow a different set of procedures by obtaining a work order.

But under Simple Approval, they just notify central dispatch and set out to work. A worker also needs to set a predetermined, safe, and clear location to move to once he or she sees a train coming.

Almanza said a lingering question is whether the section of the track Daniels and Sheppard worked on fell under the standards of the 15-second rule.

He said the track near the accident “crested the hill a little bit.” Having a sight line is important, he said, because you can’t use your ears to hear a train coming.

“It’s like a jet flying over you, you don’t hear it until it’s past you,” he explained. “I always teach in my class: ‘You don’t listen for trains, you look for trains.’”

It’s not clear at this point if the workers tried to get out of the way of the train or were caught completely by surprise. But when the workers follow the letter of the 15-second-rule to a tee, he said, they see a train coming and retreat to safety.

A helmet at the scene of the crash, which a source says is posisblyfrom one of the workers fatally struck.

Relearning

Another rule explicitly outlines that for every five or fewer workers present on the tracks, at least one must be a “watchperson.” It was created only after another unfortunate accident, in which a train fatally struck a BART worker.

“This was a new rule that came out in 2009 after James Strickland was killed,” Almanza said, darkly.

The rule is explicit: BART workers can get simple approval to work on a track without a watchperson only when “a person is moving from one location to another and the person’s full attention is focused on watching out for trains or other on-rail vehicles.”

It is not yet known if the workers inspecting the rail were inspecting the rail while moving, or if they were stationary.

Audio from the dispatch when the fatally struck workers were discovered, obtained by freelance journalist Matthew Keys.

Even more perplexing, though, is why their watchperson missed the oncoming train, Almanza said, because these workers had years of experience. Paul Oversier, BART’s head of operations, also confirmed the men in the accident were experienced professionals.

“These are two long-term railroad track specialists, I cannot overemphasize how long they’ve been in the business,” Oversier said at a press conference just after the accident. “They understand the railroads and understand moving trains, they were doing today something they’ve done a thousand times.”

But even experienced workers need to be recertified in safety protocol, Almanza said.

BART employees are required to test for safety certification once every three years, and contractors must test for safety annually. That leads to a lingering question: were all of the workers involved in the accident certified in safety? There were three sections of workers involved, Almanza said. The train operators, central control, and the workers on the tracks themselves. With most of the experienced transit workers on strike, BART has not yet revealed if the replacements were all up to date on safety protocol.

In fact, when a reporter asked Oversier at a press conference if he knew who the driver was, he replied, “no, we don’t,” adding, “we believe the train was under (Automatic Train Operation).”

A computer was in control of the car, essentially.

Flowers left near #BART tracks where 2 workers killed yesterday. @ktvu pic.twitter.com/7bAA5DEfFi

— cara liu (@CaraSFBay) October 20, 2013

While the BART community continues asking questions, it also prays for those it lost. A vigil was held for Sheppard and Daniels yesterday, and flowers can be found on the fence near the accident. For a short time, the bitterly divided BART union and management have an unfortunate common ground.

They’re both grieving the loss of their own as they look for answers.

Vigil at Walnut Creek #BART station for two men killed in yesterday’s track accident @ktvu pic.twitter.com/a5Kjv4zhNs

— cara liu (@CaraSFBay) October 21, 2013