Collaborative consumption, aka the shareable economy – the labels given to a new generation of Internet-based companies that facilitate peer-to-peer exchanges of goods and services – certainly has some positive attributes. But does it really live up to the overhyped claims of its biggest boosters, who evangelize it as a “revolution” that forever alters the economy in only positive ways? Have they really figured out a way to create something from nothing, or are there hidden costs, impacts, and complications?

I was hoping to hear that kind of balanced discussion today at a symposium hosted by the University of San Francisco’s Department of Hospitality Management, featuring What’s Mine is Yours author Rachel Botsman and Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky giving the keynote luncheon address: “The Rising of the Sharing Economy: How is it expanding the Global Hospitality Industry.”

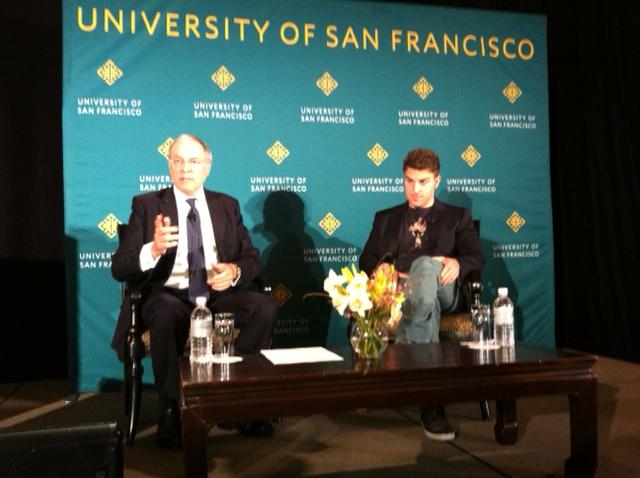

Moderated by the department’s administrative director, Dr. David Jones, I thought I’d hear a little academic skepticism, particularly given the hotel industry’s concerns about unfair competition from Airbnb. And I wanted to ask Chesky directly why his company isn’t paying the $1.8 million per year in Transient Occupancy Taxes that it owes to the city, as well as how his business model relies on hosts who are violating their leases and tenant protection laws here, in New York City, and other cities.

Instead, all I heard was uncritical boosterism, grandiose claims, creepy futurism, and the unfettered hubris of a 31-year-old CEO who claims to be altruistically saving the world while getting filthy rich in the process and refusing to even pay the local taxes that a fair public process concluded that Airbnb and its hosts owe. And after Dr. Jones failed to ask the questions I had submitted and cut off the Q&A early, Chesky turned and darted out a back door before I could ask him myself (his company’s spokespeople also still haven’t responded to my inquiries from last month).

Everyone just seems so enamored of what Botsman called “the wonderful world of collaborative consumption,” with its focus on economic “disruption,” that tech-lovers label she used over and over, without really stopping to think about the impacts of disrupting established economic and regulatory systems.

“This isn’t a threat to the hospitality industry, it’s a massive opportunity to innovate,” she enthused, claiming it would only make the economic pie bigger, with no downsides.

Chesky then told the story about how he and a buddy slapped together the Airbnb website in three days to advertise the flophouse they turned their San Francisco apartment into using air mattresses in advance of a design conference, an idea that has now blossomed into a multi-million-dollar business that places about 100,000 guests each night around the world.

“It’s like the United Nations at every kitchen table. It’s very powerful,” Chesky said of the social benefits of his company. “I think we’re in the midst of a revolution and not a lot of people are talking about it.”

Actually, it seems that everyone is talking about collaborative consumption these days, which is why Chesky was recently on the cover of Forbes and The Economist. But not a lot of people seem to be asking tough questions or challenging assertions that Chesky and his young bretheren are making, such as, “For us to win, no one has to lose.”

That would have been a good time for Dr. Jones to ask, “If that’s true, why are you refusing to pay the $2 million in TOT you owe the city, money that helps pay for Muni, street maintenance, the police, and other city services that visitors use?” Because the more Airbnb wins business from traditional hotels that do pay the TOT, the more the rest of us lose.

Similarly, in big, expensive cities that have developed complex systems regulating landlord-tenant relations – an essential system that determines who gets to live in these cities and how diverse and inclusive they remain – Airbnb offers a mechanism for circumventing those rules, a system it barely even acknowledges.

I’ve used Airbnb, and I understand that it can be a cool way to avoid expensive hotels and meet locals while traveling. That’s great. But it’s just not that simple, and it’s simplistic to focus simply on its benefits, divorced from the larger economic and environmental systems in which is operates.

“This is not a niche phenomenon. This could have enormous historic precedence,” Chesky said, later adding, “This is like a Golden Age we’re going to be entering.”

It is an age when anyone can become an entrepreneur and get rich, when the system of mass production itself will be replaced by the myriad ideas of people like Chesky in unforeseeable ways. “I think it will change dramatically the hotel and restaurant industry,” Chesky said. “Hotels themselves are going to be much more local and personal.”

He envisions the next generation of hotels creating rooms that cater to the individual tastes and preferences, from the music piped into the room to what’s in the mini-bar, all discerned from Facebook and other online mechanisms that create what Bostman called our “digital exhaust.”

“Consumers aren’t strangers, they all have profiles and you can know everything about a person,” Chesky said, sending the chill of dystopian futurism down my spine.

And we’re all going to travel freely around the world, owning little, sharing everything, and elevating Airbnb and its allies into the “trillion-dollar-industry” he’s pushing toward.

“We’re wired to be nomads,” Chesky said. “We’re going to be moving all over the world much more.”

So says the young, entitled CEO who doesn’t even have a home, flitting around the world to stay with various Airbnb hosts. But for most of us, air travel is still expensive and our vacation time is limited. And from the perspective of climate change, nothing could be worse for the environment than substantially increasing air travel to facilitate this expanded globe-trotting lifestyle that Chesky envisions.

The environmental claims of collaborative consumption companies have always struck me as the most overblown. That’s why I also cornered Adam Werbach – who went from heading Sierra Club to working for WalMart on its sustainability programs to launching Yertle, a stuff-sharing website – at an event promoting the new company on Monday, aka Earth Day.

“There’s nothing that’s green,” Werbach said when I asked whether Yertle was. “I’ve never used the term green.”

But he does make the argument that facilitating sharing allows less stuff to be produced overall, which is good for the planet.

“Is sharing a greener alternative than buying new?” he asked, citing examples such as pasta- or bread-makers as products that people may want to try without buying. “Can you find a way to sample or test those things without buying a new one?”

That’s true, but as I perused the pages and pages of stuff available on Yertle – which is sort of a high-tech version of a garage sale or thrift store, except that everything is free – I couldn’t help but be struck by its promotion of materialism and accumulation. Can we really tackle big environmental challenges and still keep all our toys?

Werbach, who graciously indulged my questions, admits that the shareable economy can’t adequately address big problems like climate change, which will require a major cultural and economic shift. It’s more like tinkering on the margins, and making some positive incremental changes, as he felt he was able to do at WalMart. “I do think we made them somewhat better. But, has it been adequate? No,” he said.

His Yertle co-founder Andy Reuben was someone Werbach met and worked with at WalMart. Reuben seemed even more hopefully that the younger generation will use collaborative consumption to create a lighter footprint on the planet.

“One thing we’re seeing is it will be an asset-light generation that can just get it and pass it on,” Reuben said, describing Yertle as “based on better utilizing the stuff what we have.”

That’s a goal that most of us probably share, and one that the shareable economy can certainly help us address. But its big boosters – from venture capitalist Ron Conway down to the random techie true believer – have to be willing to engage in an honest discussion with the rest of us, rather than just bulling their way forward, heedless of their impacts and dismissive of our concerns.

Maybe Lyft and Uber have a role to play in augmenting San Francisco’s taxi system, but we shouldn’t destroy that taxi system in the progress. Yes, City Care Share and Zipcar enable people to sell their cars, but how do they actually impact the number of cars on the roads? Airbnb is certainly a popular site with both hosts and guests, but that doesn’t mean it should be exempt from taxes and regulations.

After today’s event, I spoke with Dr. Jones – a longtime Bay Area tourism booster with a fairly libertarian outlook – about why he didn’t ask tough questions or express more skepticism. “I’m really not [skeptical]” he said, although he did note the dearth of academic research on collaborative consumption and the validity of some of my questions.

“There’s a massive value shift and there’s no way we’re going back,” Botsman said of the rapid rise of the shareable economy and its disruption of traditional economic models. That may be true, or that may be self-serving hype, but either way, it’s worth talking about in an open and collaborative way that involves more than just the insular tech world.

Last year, Mayor Ed Lee and Board President David Chiu announced the creation of a shareable economy task force, which was supposed to be reporting back some recommendations about now. I asked the Mayor’s Office of Communications for an update on its status three days ago, and I’m still waiting to hear back.

Meanwhile, Chiu’s office is still negotiating complicated legislation that would govern Airbnb’s operations in San Francisco, so there will likely be hearings on that company and the issues it raises this summer. That’s important for a city like San Francisco that is so diverse and engaged.

If San Francisco wants to help lead this collaborative consumption revolution that we keep hearing about from Lee and other boosters, hopefully we’ll also take a clear-eyed and precautionary view of what this brave new world looks like, how it’s regulated, what its byproducts may be, and whose interests it serves.