It was late at night by the time New Latthivongskorn, then 22, finally started to make his way home from the University of California Berkeley campus after a long night of studying for midterm exams. A third year molecular and cell biology major who was trying to keep up his grades in preparation for med school applications, Latthivongskorn said he noticed a man in a black hooded sweatshirt walking toward him as he approached his home. At first he didn’t think much of it – but just as he was about to unlock the door to his apartment, the young Thai student heard a voice. “Give me everything you’ve got,” the man commanded.

“I looked at him, and I looked down, and I saw a gun pointed straight at me,” Latthivongskorn recounted. Terrified, he tried to stay calm and simply cooperated; handing over his backpack and cell phone, silently feeling relieved that he hadn’t been carrying his laptop. Fortunately, Latthivongskorn was able to proceed into his apartment unscathed after the man who robbed him at gunpoint vanished down the street.

When his concerned housemate asked if he wanted to file a police report, Latthivongskorn faced a dilemma. “Yes, I wanted to report it,” he told the Guardian in a phone interview, “for me, but also for the community. That same man ended up mugging another individual later that night.”

But there was a problem. Latthivongskorn had moved with his family from Bangkok to Sacramento when he was just nine years old – and despite the fact that his entire life was rooted in California, he’d never obtained U.S. citizenship. Any interaction with police, he feared, could place him in jeopardy – even if he was approaching law enforcement as a crime victim.

“In the end, I couldn’t call,” he said. “What was going through my mind was thinking of all the sacrifices that my family had made for me … and I worked so hard to get to this point, and I’m still not there yet.” His decision not to report the armed robbery came down to “the simple fact that it could all end – that I could get deported.”

Fast-forward to today, and Latthivongskorn has graduated and earned a spot on the waitlist at Stanford while he awaits responses from a number of other med schools. He’s also active with ASPIRE, Asian Students Promoting Immigrant Rights through Education.

On April 9, he shared his experience of being mugged with California legislators at a hearing of the Public Safety Committee, and urged lawmakers to approve the TRUST Act.

Authored by Assembly Member Tom Ammiano, the bill seeks to “limit harmful deportations often stemming from trivial or discriminatory arrests,” according to a statement from Ammiano’s office.

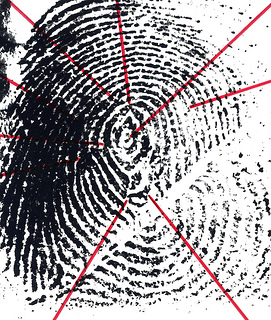

As things stand, all arrestees have their fingerprints recorded and submitted to ICE, or U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Under the federal Secure Communities program, ICE can then direct local law enforcement to hold arrestees without bail, beyond the time they’d be detained under normal circumstances, for the purposes of immigration proceedings.

The idea is to hold and deport dangerous criminals, but in practice it’s proved problematic. “More than 90,000 Californians have been deported, with 70 percent not convicted of anything, or only of lesser crimes,” Ammiano’s office points out. “Some were never charged with crimes, and some were crime victims.”

The TRUST Act would “establish a statewide policy that says if the person has not been convicted of a serious or violent felony, they would no longer be held any longer than authorities would hold them otherwise,” explained Carlos Alcalá, a spokesperson for Ammiano. The idea is to draw a distinction between violent or serious offenders, and anyone else who could be swept up in the system and needlessly held without bail.

Also on hand to testify at the April 9 hearing was Ruth Montaño, a Bakersfield woman who was arrested and nearly deported after someone complained that her dog was barking too loud.

Alcalá recounted other horror stories that had made their way to the Capitol. There was the day laborer whose employer reported him to immigration authorities at the end of his shift when all he was expecting was a day’s wage, and the woman who was arrested outside of Walmart for trespassing – and nearly deported – for selling tamales. Then there were women who reported incidents of domestic violence only to be subjected to immigration proceedings (and their counterparts, who stayed mum about abuse because they feared deportation).

Members of the Public Safety Committee approved the TRUST Act 4-2, clearing the way for the bill to go to the floor of the Assembly as early as next week. An earlier version made its way to the desk of Gov. Jerry Brown last year, but was ultimately vetoed, leading to a revised version. “Because of last session’s history, we’re hoping to have more substantive discussions with the governor beforehand,” Alcalá told the Guardian.

The timing is significant. “Immigration changes are moving quickly at the national level,” Ammiano noted, “and California needs to make changes here to keep pace.”

Advocates expect a national proposal for immigration reform to be introduced in the Senate any day now, according to Jon Rodney of the California Immigrant Policy Center. West Coast activists are planning an event April 10 to mirror a mass rally and march for immigration reform planned in D.C.

In San Francisco, the march will begin outside Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s office on Post Street and then proceed to Civic Center, where a rally is planned for 5 p.m. Latthivongskorn plans to participate along with other organizers from ASPIRE, and a host of local and regional immigration reform advocates are getting involved.

Those joining the march “will carry 1,000 paper flowers,” Rodney said, “to represent 1,000 deportations that happen every day in the U.S. That’s one piece of Wednesday’s rally, is stopping deportations.”