rebecca@sfbg.com

A little more than a year ago, Therese Chen, director of registration at San Francisco’s de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park, sent an email to another staffer concerning “Mrs. Wilsey’s new Matisse.”

That would be Diane “Dede” Wilsey, the wealthy art collector who is also president of the Board of Trustees of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

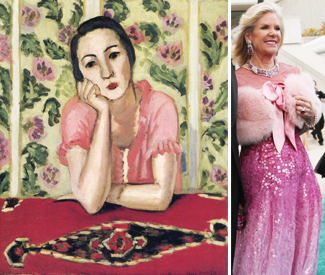

Chen asked Steve Brindmore, then a museum staff member who also runs a personal art crating business, whether he had a crate for the oil painting, which is titled “The Pink Blouse.” According to records from Sotheby’s New York auction house, the estimated value of this painting is between $3 and $4 million.

“The painting is on an A-frame in the Examination Room,” Chen wrote. “I’m taking the painting over to Dede on Wednesday … for [an event], and then it will come back here to the de Young to be crated for Portland around the week of Jan. 23.”

The exchange suggests that public museum facilities were being used to store and crate a piece of art from Wilsey’s personal collection.

Timestamps show that the exchange happened around 1:30 on a Monday, during museum hours. The correspondence was sent using museum staff email. It’s unclear what, if anything, this task had to do with the operations of a public museum. But FAMSF clearly handled a painting from the growing private art collection maintained by Wilsey, a major donor and key FAMSF fundraiser who loves Impressionist paintings and seems to gravitate toward works incorporating the color pink.

Beth Heinrich, a spokesperson for the Portland Art Museum, confirmed to the Guardian that a Matisse titled “The Pink Blouse” was indeed loaned to the museum from a private collection, and placed on display in its Impressionist galleries in February of 2012.

The email exchange between Chen and Brindmore is just one thread in a trove of correspondence, invoices, and other documentation anonymously submitted to the Guardian. Put together, the information shows museum staff being asked, during normal business hours, to handle, photograph, crate or arrange shipments for more than a dozen different pieces from Wilsey’s personal art collection in just the past two years. The documentation also shows several examples in which museum employees were directed by Chen to digitally reproduce works from Wilsey’s private collection.

It’s not uncommon for art collectors to put private pieces in the collection of a museum, nor it is unusual for collectors to lend out art to other museums. And if the de Young received some benefit from its association with Wilsey’s art, it wouldn’t be surprising (or inappropriate) for the museum to help reproduce or ship it.

On the other hand, if Wilsey is loaning out the pieces on her own, from her private collection, and using museum resources, it could raise conflicts of interest.

The de Young, for example, wasn’t cosponsoring the Portland exhibit where the Matisse was shown. Since Wilsey just bought the Matisse, it couldn’t have been part of the de Young’s collection.

There’s no indication that it was anything but her personal loan of a valuable painting — facilitated by the staff of a nonprofit that runs a city museum.

Invoices show that some staff members were paid separately for assisting with Wilsey’s art collection, in some cases through independent businesses.

WHO’S IN CHARGE?

The Fine Arts Museums include the de Young and the Legion of Honor. Included as charitable trust departments under the City Charter, they are governed by a 43-member Board of Trustees, which is responsible for appointing a director. Wilsey has presided over the body as board president since the 1990s. The bylaws of the board were changed to eliminate term limits for the president, meaning she could stay in the post for as long as her board colleagues want.

The FAMSF has been leaderless since director John Buchanan died in December, 2011.

Though the museums are public institutions, their governance structure is similar to that of a public-private partnership, since a private nonprofit organization called the Corporation of Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco handles museum administration and employs a number of museum staff, including curators and other professionals.

The city contributes some public funding to FAMSF, but the majority of revenue is derived from private sources. Wilsey, a multi-millionaire, contributed $10 million to the de Young, and spearheaded a 10-year fundraising campaign that culminated in 2005 with more than $180 million raised to rebuild the museum.

The socially connected philanthropist, known for throwing Christmastime bashes that attract a roster of powerful luminaries from government and big business to her Pacific Heights mansion, is often the subject of press reports or gossip surrounding San Francisco high society. Her stepson, Sean Wilsey, famously characterized Wilsey as his “evil stepmother” in his memoir, “Oh, the Glory of It All,” which includes an unflattering scene in which she is said to have pinned $200,000 brooches onto her bathrobe one Christmas morning.

She owns a fair amount of art — and apparently moves it around. In August of 2011, for instance, email threads show that Chen, using her FAMSF email address, contacted Jamil Abou-Samra of Masterpiece International, the shipping company, regarding “Mrs. Wilsey’s Degas.” Chen wrote: “I brought the Degas to the de Young last week for glazing. It should be ready for Steve to measure for crating any days [sic] now. Are we still looking at August 30, Tuesday, for pick up?” The thread indicates that the painting was destined for the Royal Academy of Arts, in London.

An Internet search shows that the Royal Academy indeed hosted an exhibit titled “Degas and the Ballet,” which opened in September of 2011. Press reports highlighting the artwork on display include an image of a Degas credited to “Collection of Diane B. Wilsey.”

There is no mention of the de Young or the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco anywhere in the web or press materials discussing the exhibition. Numerous other cooperating museums are identified by name.

When the Guardian reached Abou-Samra by phone, she indicated that she was not at liberty to discuss any of Masterpiece International’s handling of art shipments.

OFF TO PARIS

In February of 2011, email records show, Chen contacted Brindmore on his FAMSF email regarding a crate for a painting by Jean-Louis Forain that was bound for an exhibition at the Petit Palais, in Paris. The Parisian exhibit was launched in partnership with a Forain exhibit at Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis.

“Dede has a Forain painting that needs to be packed and crated … The painting is currently in our storage and [FAMSF staff member Steven Correll] knows the exact location,” Chen wrote to Brindmore. A few weeks later, Chen provided some special handling instructions for the Forain in an email to Samra, of Masterpiece International, just before it was transported to the airport.

There are established professional standards governing the operations of art museums, and the Guardian phoned several experts to determine whether it’s common practice for a member of the Board of Trustees to call upon museum staff members to handle their personal artwork. In response, communications director Dewey Blanton of the American Alliance of Museums highlighted an ethical standard stating, “No individual can use his or her position with the museum for personal gain.”

The code of ethics at the Boston Science Museum put it quite clearly: “When Museum of Science Trustees seek staff assistance for personal needs they should not expect that such help will be rendered to an extent greater than that available to a member of the general public in similar circumstances or with similar needs.”

It’s unlikely that a member of the general public who wanted to ship artworks would have the staff of the de Young at his or her disposal.

The Guardian telephoned a number believed to be Wilsey’s seeking comment, and was greeted with a receptionist who answered with the bright greeting, “Wilsey residence!” After being informed that Wilsey was traveling, we requested comment from her via email, explaining that documentation appeared to show use of museum time to manage her personal art collection. She had not responded by press time.

Ken Garcia, press spokesman for the Museums, told us “there are situations in which the museum facilitates loans to the Corporation of the Fine Arts Museums (COFAM), loans to other museums, and in other ways assists with the care and handling of artworks for private collectors, including trustees when there is significant value to our museum.” He added: “The reasons for museum staff to have handled the board president’s private art collection reflect standard practice for exhibitions and loans.”

He noted: “Reproductions of artworks (2D) are routinely requested by collectors when the loan of a picture conflicts with the lenders need for privacy, represents a potential security issue, or interrupts the continuity of the enjoyment of a collection. FAMSF provides for the photographic reproduction of artworks as an appreciative acknowledgment of the negotiated loan. Mrs. Wilsey has on occasion requested a reproduction be made of a loaned picture but on each occasion has generously assumed responsibility for the associated costs.”

Maybe it’s all perfectly fine and normal, “standard practice.” But there’s a lot of it going on, and some is at the very least curious.