STREET SEEN Nearing the climax of her presentation at last week’s Zero Graffiti International Conference, Vancouver PD’s graffiti-fighting specialist Valerie Spicer despaired over graffiti’s affects on its perpetrators.

“He didn’t die because of graffiti,” she said sadly, a deceased Canadian graffiti artist’s childhood photo on the PowerPoint screen behind her. “But I’m quite sure that the behaviors he learned in the subculture didn’t help him confront the man who stabbed and killed him.”

It wasn’t the only conflation between societal decay and graffiti made at the conference (www.zerograffiti.org), held Jan. 16-18 in the soaring white St. Mary’s Cathedral on Geary and Gough — the one designed so that God sees a cross when he looks down at it.

Organized by the SF Graffiti Advisory Board, anti-graffiti nonprofit Stop Urban Blight, and citizen’s group SF Beautiful, the conference gave law enforcement and city officials the chance to attend lectures on prevention and investigation of graffiti, tours of Mission and Tenderloin murals on Academy of Art buses — the school was one of the event’s sponsors, in addition to the SF Arts Commission — and a play put on by a Sacramento anti-gang and graffiti group. This last, “performed in the colloquial dialect of youth and street culture,” as the program delicately put it.

As Spicer wrapped up her tragic tale, the lights came back on in the St. Mary’s basement. I fumbled with my things I was targeted by one of the graffiti fighters present.

“Are your friends into crime?” said Monty Perrera, professional buffer for the City of Oakland. “I assume you’re probably in the subculture,” he continued (my pink-and-purple hair made for poor camouflage, I guessed.) He was wearing a T-shirt screen printed with one of Oakland street artist Gats’ enigmatic visages.

“I’ve met many of the main [graffiti artists] in Oakland,” Perrera continued, after apologizing for “promoting graffiti” with the shirt. “They don’t really trust me or like me, but…” The admission hung between us in the air.

Perrera has a healthy interest in street art — so much so, he told me, that he buffs selectively, paying special attention to “bubble taggers” (“we call them the ego artists”) and new artists (“if someone’s new I get you because you’re new. Maybe you’ll go away.”) Despite having attended East Bay street art blog Endless Canvas’ “Special Delivery” mural exhibit in an empty Berkeley warehouse twice, Perrera was adamant that the work he does removing graffiti is vital to his community. “The ego taggers just have no mercy,” he told me.

Between public and private enterprise, as the police chief asserted from the Zero Graffiti podium, San Francisco spends $20 to $30 million dollars a year combating graffiti. The Department of Public Works, which takes responsibility for quickly removing graffiti deemed motivated by gang activity, drops a cool $3.6 million alone.

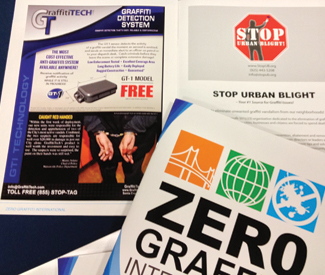

But to be fair, no one has ever asked me for cash to buy a spray can. That dollar figure is what graffiti removal costs us. And behind the rows of folding chairs at the conference, the rows of sponsoring vendor booths gave hints as to what that money could go towards. Graffiti Safe Wipes, suitable for removing paint from stone walls with a swipe. This Stuff Works! brand anti-graffiti wall coating.

Perhaps the most ominous is one of the tools our own city uses, according to SF’s DPW director of public affairs Rachel Gordon. Meet the GraffitiTech graffiti detection system, a 10″ x 3.8″ box that mysteriously detects tagging as it happens by means of “advanced heuristics and algorithms,” according to its company’s website. The sensor’s inner workings are left unexplained for fear of vandalism attempts but I’ve taken the liberty tracking down GraffitiTech’s US Patent Office full text description for those interested.

The second and final lecture open to the public that day was that of Dwight Waldo, a retired San Bernadino cop who proudly recounted tales of shutting down legal street art shows and murals by proving associated artists had drug convictions. He described the “five types” of graffiti to the crowd, and lauded the use of the Internet for its utility in researching crime (you can start by searching “tag crews fighting” on YouTube, he advised.)

“You’re going to hear things in trainings where you’ll go ‘oh I can’t do that’ because your political climate doesn’t allow it,” Waldo told Zero Graffiti attendees.

An hour later Mohammed Nuru, director of the DPW, used the podium to announce plans to fight for higher mandatory fines for convicted taggers, and to require commercial truck owners to rid their vehicles of graffiti before their registration could be renewed. Perhaps the political climate in the Bay Area is changing when it comes to the war on graffiti.