caitlin@sfbg.com

STREET SEEN To the casual observer, it may have appeared as if I had taken a painful, rainy early morning Muni ride into SoMa for the sole purpose of eating plastic-wrapped Japanese pancakes filled with red bean paste in a chain store. But to adherents of the Muji phenomenon, I was actually witnessing the birth of cross-Pacific retail revolution.

“The minimalism of Muji fits San Francisco perfectly with what the city is trying to do with conservation,” said store manager Eric Kobuchi, who was standing with the cash registers behind of him, and the sleepy-eyed attendees of the November 30th press preview and reception in front of him. His company was to open its first West Coast location (540 Ninth St., SF. www.muji.us) in an hour-and-a-half.

Among minimalism aficionados, this brand is paramount. Muji was born in 1980, originally as a line of 40 house and food items that were sold in Seiyu supermarkets. The name itself means “no label, quality goods.” The items were cheap, but relatively high quality. These savings were possible, said the company, by simplifying packaging and production, and utilizing offbeat materials, like the parts of the fish near the head and tail for its canned fish.

Muji fans kindled to the line’s recycled, plain packaging (the company has courted the “sustainable” label for decades). Being a Muji consumer is an identity unto itself, at least according to the brands’s brilliant ad campaigns. From a 256-page coffee table book of such endeavors presented to me at the preview: “Muji tries to attract not the customer who says ‘This is what I want,’ but rather the one who says, rationally, ‘this will do.'”

Zen. Today, Muji’s selection is an Ikea-Gap mélange. The San Francisco location, says Azami, has a similar, but smaller product selection (minus the food — tight regulations here make importing comestibles complicated), and the same layout and presentation as its Japanese stores. I don’t doubt that little changes have been made to the Muji formula for its West Coast audience — during the press preview, display prices for some of the stock were still only visible in yen.

Muji is but one simple, made-from-recycled-material package in a shopping bag full of newish Japanese brands to hit the Bay Area. Daiso, in my eyes the epitome of dollar (or rather 100 yen, roughly $1.50) store excellence, has been plying lunch boxes, fake eyelashes, party wigs, and stationary on the West Coast since 2005. It has several stores from SF to Milpitas (SF locations at 570 Market and 22 Japantown Peace Plaza).

We have homegrown Japanese retailers as well. Lounging in a bright office lined with shelves of Japanese comics, Seiji Horibuchi explained to me how he came to open retail complex New People (1746 Post, SF. www.newpeopleworld.com) in the heart of San Francisco’s Japantown.

Dressed in head-to-toe Sou Sou, a neo-traditional line of Japanese worker comfortwear whose signature item is its brightly patterned split-toe shoes, Horibuchi says he moved to the city in 1975, and started his anime-manga publishing house Viz Media in his adopted city in 1986. Viz Pictures, a distribution company for Japanese films followed, and then New People was born, originally as a movie theater at which to play Viz titles.

But the project grew, and by its opening in 2009, the J-pop mall included a gift shop, art gallery, and entire floor of Japanese fashion brands like Sou Sou and the babydoll goth Lolita brand Baby, the Stars Shine Bright.

New People is a bit different than the new megachains in town, however. Even the casual visitor can tell Horibuchi’s inventory couldn’t have come from any other country — unlike a lot of Muji’s stock, comprised of simply-universal products, most of New People’s vinyl dolls, high design flatware, and frilly babydoll bonnets could really have only come from Japan.

But Horibuchi understands why brands like Muji choose San Francisco for their debut on this side of the country. “We’re more open to foreign culture,” he says. “San Francisco is very flexible, livable.”

Plus, Asian Americans make up nearly 36 percent of the city’s population — and that ratio has grown in recent years. Companies know that many residents are already familiar with their brand, Horibuchi says. “I’m sure they’ve done enough marketing research.”

A company that has certainly done its marketing research is Uniqlo, which opened a popup shop (117 Post, SF) this summer, then a full-size West Coast flagship store (111 Powell, SF) in Union Square in October. In its opening weeks, the latter attracted 100-plus-person lines of shoppers with cheaply-priced rainbows of colored denim and ultralight down jackets.

In a calm moment on a busy holiday shopping day, I got a chance to talk with Uniqlo’s John “Jack” Zech, a “superstar store manager” according to a publicist that sat with us while we talked.

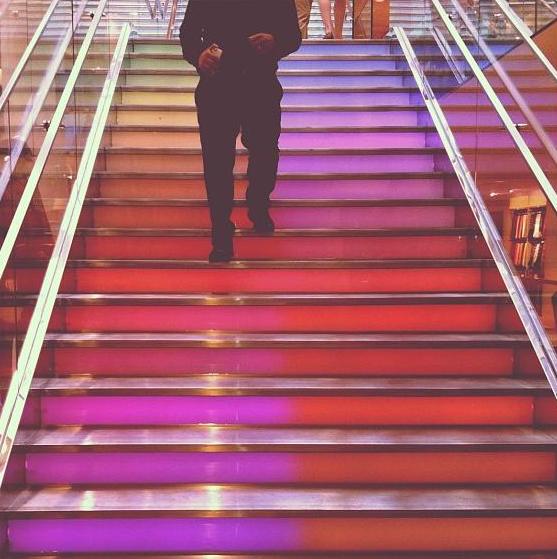

The three of us had a view of Uniqlo’s specially-designed-for-SF “magic mirror” (put on a down jacket, press a button, and the hue of your garment in the reflection shifts through the line’s different colors), its staircase of melting rainbow tones, and slowly rotating armies of mannequins clad in ski-ready fashions, ensconced in glass cases.

Zech worked in Uniqlo’s Japanese locations for months before the SF stores opened, and he says the company’s goal is to bring the Japanese concept of supreme customer service, irrashai mase, to the rest of the world.

When you walk into Uniqlo, a person in a happi day kimono greets you warmly. But other than that, I couldn’t see much of a difference between the cheery sales staff there versus that of any of the other chain stores in the neighborhood.

You won’t find happi on sale at Uniqlo. Instead, its affordably-priced cashmere, “Heat Tech” clothing — that I promise you, actually tingles and heats your skin up — and $9.90 packable raincoats (the only clothing item made specifically for the SF store) dominate the sales floor.

In 2010, the company’s official language switched to English. All managerial staff worldwide is required to speak it. “We found that people basically need the same things in Japan, France, London, here,” chirps Kech. “[CEO] Tadashi Yanai thinks we can improve the world by being a global company.”

Which snapped me out of the reverie I’d been lulled into by banks of $29.90 beige boot-cuts. Are Uniqlo and Muji really all that different than the globalized brands from the United States? Walmart, after all, has store greeters.

“If the product is good, it will sell,” regardless of geography, Horibuchi told me. These big brands have real cute stuff (admittedly, I would like to draw Santa’s attention to Muji’s $38 cardboard MP3 speakers.) But you’re not being worldly by shopping at them, though you are being globalized.