cheryl@sfbg.com

FILM With a running time of just under three hours, writer-director-star Patrick Wang’s In the Family rewards patient viewers with its quietly observed tale of a man battling for custody of his son.

Wang’s debut feature has already earned local acclaim, picking up both the Best Narrative Feature Award and the Emerging Filmmaker Award at the 2012 San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival. It returns in an expanded engagement right when Hollywood is rolling out its flashiest year-end fare, which In the Family neither resembles nor aspires to resemble; its story unfolds via remarkably low-key scenes, most of which are shot using extremely long single takes. Not many films, even self-produced indie dramas, dare allow so much breathing room into each sequence.

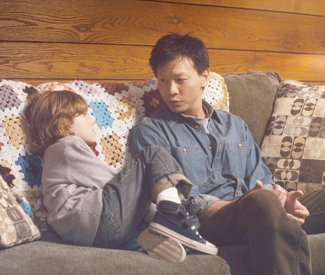

This technique works, for the most part, because the story is so compelling. Joey (Wang) and Cody (Trevor St. John) are a well-matched couple in small-town Tennessee, busy with jobs — Joey’s a contractor; Cody’s a teacher — and raising six-year-old Chip (Sebastian Brodziak, who delivers a natural performance that’s thankfully more precocious than precious). Their home life is relaxed and routine, focused on their lively, dragon-obsessed boy. In the Family takes its time revealing their relationship’s origins, with flashbacks so briskly edited they stand out in contrast to the film’s otherwise unhurried pace. Chip’s mother, it turns out, is Cody’s late wife; some time after her death, it’s Cody who initiates a romance with the laconic, truck-driving guy who’s been helping renovate his house.

But even before we learn this, tragedy strikes: a car accident gravely injures Cody. The first sign of In the Family‘s looming drama occurs at the hospital, where Cody’s sister Eileen (Kelly McAndrew), brother-in-law Dave (Peter Hermann), and mother Sally (Park Overall) have gathered. When a nurse insists that “only family members are allowed to visit,” nobody stands up for Joey. When Cody dies, grief washes over everyone. Tempers flare when it’s revealed that Cody’s will is six years old, written before his relationship with Joey. When they were together, Joey admits, “We didn’t talk about the big stuff” — and the legal consequences are devastating. Guardianship of Chip, it seems, goes to Eileen.

“Nothing makes sense,” Cody weeps to Joey during a flashback that takes place right after his wife’s death. It’s a sentiment Joey fully understands, but Wang avoids scenes of tear-stained arguments or other typical melodrama clichés to convey the depths of his character’s despair. A particularly moving flashback recalls the night the two first kissed after bonding over Chip Taylor tunes (the songwriter cameos in the film, and his melancholy music is a recurring motif). In the next scene, set in the film’s present, Joey is wearing the same striped shirt Cody had on that night.

In the Family‘s biggest contrivance is containing most of its last act in a deposition scene, complete with a cartoonishly slick lawyer whose cruel questions make sure the viewer knows that homophobia (and racism) are both themes here. Joey’s response is a lengthy monologue loaded with exposition (and probably more words than the rest of the script’s pages, combined). It’s a bottom-heavy ending to a film that otherwise prefers observing at a distance — shooting Joey from behind rather than showing his face when he learns that Cody has died; allowing important action to occur off screen or behind closed doors; and using its long, wordless scenes to convey delicate, organically-shifting emotions. It’s a “message movie” that prefers subtlety over speechifying, and is all the more powerful for it. *

IN THE FAMILY opens Fri/7 in San Francisco.