It’s a symbol of the atrocities suffered by Chinese Americans on this continent: a lumbering machine that stripped thousands of their livelihood and was even named for the epithet used against them, the Iron Chink.

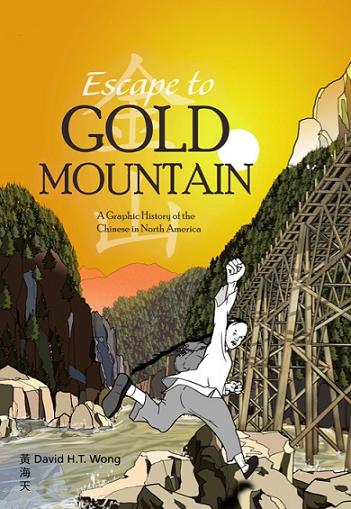

For Escape To Gold Mountain graphic novelist and community activist David H.T. Wong, who will read from the book at a Sun/11 event in Berkeley’s Eastwind Books, the 1903 invention of the mechanized fish gutting machine that stole cannery jobs from Asian immigrants — who already had to fight racism to find jobs at all — made the perfect title for his historical graphic novel.

But, and perhaps this is a sign of the historical progression that Wong converted into panels for us in his graphic novel, things just don’t get named the c-word anymore.

“Though it’s a historically accurate name of a real artifact, people today will not accept these sorts of racist terms,” writes Wong in the afterword of Gold Mountain. The name was changed before it was officially released.

We don’t get enough Chinese history in the United States. Growing up, even in a Sunset District public elementary school that had 90 percent Asian American students, the only thing I recall learning about the Asian diaspora here was Chinese New Year, Japanese internment camps.

This is a wrong that Wong’s Escape to Gold Mountain corrects, and in comic book form at that. The book follows Chinese laborer Wong Ah Gin to the United States, where he becomes inextricably linked with the capitalists’ quest to build a railroad across the United States.

The task was accomplished using Asian immigrant labor, the cheapest on the market. After the coasts were connected, many communities rejected the workers who made the task possible. We all know this story: use immigrant labor to accomplish previously-impossible tasks, then castigate the same people for stealing jobs.

In the case of Asian communities in the United States and Canada, this xenophobia lead to extreme violence. In 1885, mass killings occured in Wyoming and Washington. Tacoma’s Chinatown was even burned to the ground by bigoted townspeople. After the physical violence came the bureaucratic castigation: elaborate immigration codes that stopped refugees from coming to North America and separated parents from their kids.

Escape to Gold Mountain wends its way through all this injustice via Wong and other characters, ending up at a Chinese restaurant in Victoria, BC. The author’s panel work makes an at-times painful history easily read (my only quibble is small: why must most of the characters’ mouths be frozen in mid-word?)

Spoiler alert: there’s a hopeful ending. Escape to Gold Mountain ends on a look at the Chinese Americans who have been elected to public office in the 20th and 21st centuries, and a real-life reconciliation story that will make you grateful for your own awkward trips home for the holidays.

The comic is really a jumping-off point for those interested in the subject matter — the epic research that Wong put towards the book made for enough bibliography and reading resources to launch a thousand syllabi, or at least a sense that an important portion of history may have been missing from your childhood textbooks.

David H.T. Wong reads from Escape From Gold Mountain

Sun/11 7pm, free

Eastwind Books

2066 University, Berk.