yael@sfbg.com

“I was 18 years old the first time they locked me up in a psych ward.”

So begins “The Bipolar World,” an article published in the Bay Guardian‘s literature section 10 years ago, on September 18, 2002. The writer, Sascha Altman DuBrul, tells the story of his life. He’d been arrested walking on New York subway tracks after the year he first experienced what would later be diagnosed as bipolar disorder.

In the article, DuBrul wrote that the ideas shooting through his head were like a pinball game and he was convinced the radio was talking to him and that the CIA was recording his thoughts via secret neurotransmitters under his skin. But when he was diagnosed and told that he would need to take daily pills for the rest of his life, he wrote, “I wasn’t convinced, to say the least, that gulping down a handful of pills every day would make me sane.”

“I think it’s really about time we start carving some more of the middle ground with stories from outside the mainstream and creating a new language for ourselves that reflects all the complexity and brilliance that we hold inside,” the article concludes.

DuBrul was right—the time was ripe.

“Within a couple of days of it being out on the street, I got about 40 emails from strangers,” DuBrul told me. “And it wasn’t just one or two line emails that were,’ hey, great article.’ It was people pouring out their stories to me.”

One of those people was Oakland artist Jacks McNamara, and the two instantly connected.

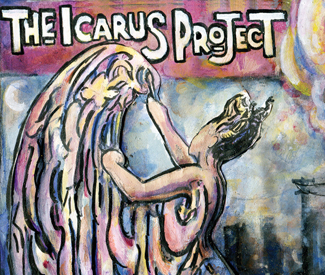

“You know the myth of Icarus, right? It’s the boy who flies too close to the sun. It’s from Greek mythology. So we were two people who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and we were like, instead of seeing ourselves as diseased or disordered, we see ourselves as having dangerous gifts, like having wings,” DuBrul said. “And so, we put up a website that said, ‘The Icarus Project, navigating the space between brilliance and madness.'”

The Icarus Project began as a website, whose forums quickly filled with discussions as more people shared their stories and connected. Today, The Icarus Project has published three books, including a guide to starting support groups, dozens of which have sprung up around the country. More than 14,000 people have registered on the website.

The Bay Area-born radical mental health project celebrates its 10 year anniversary this year. An art show, concerts, spoken word, film screening, and skill share will take place this coming week. “Icaristas” will do what they do best: share their stories in language that feels right, building connections and community.

“When Sascha and I started it, we’d never seen anything written about bipolar that we could relate to. Everything was sterile and clinical and very mainstream, and didn’t really situate these sort of struggles within a larger political context,” McNamara recalls.

Now, there are Icarus Project books translated into six languages, and a huge collection of writing and art in what one zine editor, Jonah Bossewitch, calls the Icarus “sphere of influence and inspiration.”

“Our lives are made of fleeting moments, and to create documentation — whether in print or online or on canvas — is to make a fleeting moment into something to be shared. The Icarus Project and others who share similar ideas of liberation need to live our lives of beautiful fleeting moments, but also need to create documentation so that we can be heard,” said Laura-Marie Taylor, creator of Functionally Ill, an Icarus-inspired mental health zine now in its 13th edition.

“We’re in competition with the loud voices of psychiatry, advertising, governments, and other forces that want to tell us who we are. We need to broadcast our stories far and wide in order to counteract the forces that want to tell us who we are,” Taylor said.

That was also the view of Ken Paul Rosenthal, whose film, Crooked Beauty, will be screened at the 10-year anniversary celebration.

“She who does not write is written upon,” Rosenthal told me. “Society’s narratives will overwrite your authentic self.”

“I think more than anything, Icarus is about hearing stories,” he said.

And that story telling is intimately connected to the building of community and networks.

Rosenthal first got acquainted with Icarus when he read a line Mcnamara had written: “The world seemed to hit me so much harder and fill me so much fuller than anyone else I knew. Slanted sunlight could make me dizzy with its beauty and witnessing unkindness filled me with physical pain.”

“We really wanted to create materials that were beautiful and inspiring and that people actually wanted to read,” said McNamara. “And that they could relate to if they came from more of a subcultural perspective or just had suspicions about the mental health industry and the ways that it diagnoses people and treats them. “

Icarus concepts also spread through means other than their support groups and publications.

“A lot of long-term Icarus members have gone on to become social workers, or to become therapists, or in various ways to have careers that are based in mental health and are bringing alternative perspectives,” McNamara said.

One such Icarista is Kathy Rose. She met McNamara at a screening of Crooked Beauty in 2010, and began participating in support groups and volunteering with Icarus. A teacher at Five Keys Charter School, which operates in San Francisco county jails, Rose said that the understanding and language of mental health she got from Icarus have been useful in her classroom.

“I see how many of my students are struggling with their own mental health, how they are treated, and how so much is related to the trauma they’ve experienced in their lives and lack of support,” said Rose. She said that she has used Icarus materials in the classroom and screened Crooked Beauty.

Those materials explore questions of over-medication and independence and autonomy in decision-making and question the role of institutions like psychiatric hospitals and prisons.

“Institutionalization in prisons and mental hospitals isn’t helping anyone and isn’t getting us anywhere,” Rose said.

The Icarus Project isn’t the first effort to resist the mental health establishment. The Mental Patients Liberation Front, and the larger Psychiatric Survivors movement grew out of civil rights efforts of the 1960s and 70s, as patients demanded an end to coerced and forced psychiatric interventions like electroshock. Today, Mind Freedom International and other groups continue that pressure; most recently, hundreds protested an American Psychiatric Associations meeting discussing new definitions for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition on May 5.

The Icarus Project is also intimately connected to activist movements, but plays a unique role.

“There’s support networks that get started in activist communities, but there’s a lot of ways that people have a really hard time being supportive of each other if they haven’t done the work themselves to be able to be supportive of themselves,” said DuBrul. “What happens in activist communities is that people burn out, which is kind of the ultimate Icarus project. I mean, that’s the Icarus myth.”

He called the Occupy movement, with its distinctive tent cities packed with people, many of whom were hurting financially and emotionally, a “test case” for implementing Icarus concepts.

In fact, Occupy has led to yet another Icarus-inspired book, Mindful Occupation, due to be released this year. The book “aims to address the need for attention to mental health, healing, and emotional first aid within Occupy and other movement groups.”

Mental health professionals, along with other non-professionals who were a part of Occupy Wall Street, formed the Support working group to intervene when people seemed to be in crisis and patrol the park at night. But Jonah Bossewitch, a member of the working group and one of the editors of Mindful Occupation, said that the broad critique of society and authority present in most of Occupy didn’t always extend to Support.

“Nobody was going to go to the cops after people got into a fight. Yet people were getting forced treatment and psych evaluations, ” Bossewitch said. “Folks are ready to critique the outside world — capitalism, banks — but it’s way harder to look in at their own profession.”

For DuBrul, the emotional tensions that played out at Occupy, as well as the trauma of police beatings, jail, and exposure to chemicals, proved the need to continue and grow The Icarus Project.

“If you know how you are when you’re well, it’s much easier to get back there,” said DuBrul said. “I’m telling you, a movement full of people, an Occupy movement full of people that have a sense of how they are when they’re well, then it’s much easier to work towards what it is that you want. If you’re operating from a place where you’re having a really hard time, it’s much harder to get to where you’re going.”

So where is Icarus going? They hope to formalize the mentorship and education that has already happened, borrowing in some ways from the “sponsorship” approach that groups like Alcoholics Anonymous take.

“We started with a vision of creating a new language and culture about what gets considered mental illness,” DuBrul said. “It’s alright to be ‘mad’ and still be brilliant.”

The schedule of Icarus anniversary events is available at www.theicarusproject.net/10thanniversary