yael@sfbg.com

On May 24, a panel of three Jewish activists and authors from the Bay Area will discuss the historical figures and ancestors that inspire their work today. The event was originally scheduled to take place at the Jewish Community Library, operated by the Bureau of Jewish Education (BJE), which is largely supported by the Jewish Community Federation (JCF, or “the Federation”).

Leaders at the BJE canceled the event in January after discussions about its content with organizers of the panel, who then found another venue: Congregation Sha’ar Zahav. That seemed like a harmless turn of events that has nothing to do with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, at least not directly.

But with the current state of discourse in the Bay Area’s Jewish community, just beneath the surface are complex dynamics that raise issues of censorship, bonds forged by religion, whether certain criticisms of Israel should be off-limits, and a battle for the hearts of minds of Jews in the diaspora.

Anti-war activist Rae Abileah has found herself at the middle of this battle. She is on the panel to discuss her great uncle Joseph Abileah, an Israeli pacifist who was charged and tried in 1949 after he refused to join the army as part of Israel’s mandatory military service.

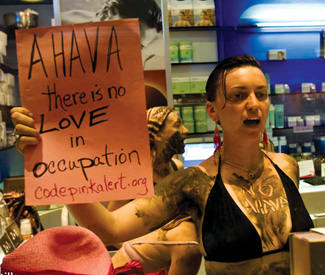

Abileah is a member of Code Pink who is outspoken about her opposition to the Israeli occupation in Palestine. The panel is meant to discuss decades-old work, not the current state of affairs domestically or in Israel, but Abileah’s inclusion made it too political for some.

In March, the panelists — which also include Julie Gilgoff and Elaine Elinson — and event organizer Diana Scott wrote an open letter to the Jewish Community Library saying, “We find it particularly troubling that an act of censorship has occurred at the Library — an institution that it supposed to be a symbol of open thought in learning in the Jewish Community.”

David Waksberg, the director of the BJE who was instrumental in the decision-making process, said it was nothing of the sort. “We had very honest, productive, and respectful discussions about why the program wasn’t for us,” he told me.

The letter concludes: “We seek to make clear that Federation policies, designed to foster the appearance of Jewish solidarity by shutting down the vital exchange of ideas in the Jewish community, are divisive and intolerable. They are also ultimately ineffective in suppressing dissent, and, paradoxically, undermine the values and mission of some of our most cherished Jewish institutions.”

“The Jewish Community Federation didn’t tell us whether or not to do this program,” Waksberg insists. “They didn’t pressure us one way or another.”

The open letter also discusses funding guidelines, adopted in 2010 by the Federation. The guidelines restrict funding for events that “endorse the BDS (boycott-divestment-sanctions) movement or positions that undermine the legitimacy of the State of Israel.”

DELEGITIMIZING ISRAEL?

The guidelines have meaning beyond these specific circumstances. They represent a conflict in what counts as diversity of opinion, what counts as dissent, and the incredibly loaded concept of “delegitimizing Israel.”

The guidelines were a response to a controversial 2009 screening of Rachel, a documentary on the life of Rachel Corrie, a 24-year-old who was killed when she stood in front of a bulldozer on its way to level a Palestinian home. The film was screened at the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival followed by speaker Cindy Corrie, Rachel’s mother. The film-going crowd yelled and booed, and the Federation threatened to quit funding the festival.

The next year was declared by some Jewish leaders to be the Year of Civil Discourse. The Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC), the self-described “central public affairs arm of the organized Bay Area Jewish Community,” organized a year of programming and discussion, with an aim to “elevate the level of discourse in the Jewish community when discussing Israel.” The J Weekly, the magazine of the Jewish Bay Area, reported that “[organizers] agree that the Year of Civil Discourse was a success,” though these organizers acknowledged their work was far from over.

Indeed, the controversies rage on. Two months before the Year of Civil Discourse officially ended Dec. 13, the Museum of Children’s Art in Oakland canceled an exhibit, “A Child’s View from Gaza”, that would have showcased drawings by Palestinian children, after pressure from Jewish organizations.

The director of the JCRC, Doug Kahn, became a spokesperson against the exhibit, butting up against groups like the Middle East Children’s Alliance and Bend the Arc (formerly Progressive Jewish Alliance). In March, an event that would have featured author and journalist Peter Beinart lost support after the JCC of the East Bay learned that one of the event’s moderators was on the board of Bend the Arc. Add this panel to the mix, and the six months since the Year of Civil Discourse ended have proven how taboo topics like BDS and Israeli violence in Palestine remain volatile.

BDS in particular has emerged as an untouchable issue. The campaign is a result of a 2005 Palestinian call for boycott and divestment from Israeli companies, and economic sanctions on Israel. BDSmovement.net, which provides news and background information regarding BDS efforts, lists three goals to the protest: “Ending [Israel’s] occupation and colonization of all Arab lands and dismantling the Wall; recognizing the fundamental rights of the Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel to full equality; and respecting, protecting and promoting the rights of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and properties as stipulated in UN resolution 194.”

The campaign has seen effects worldwide. Abileah has organized to promote BDS, in particular working to get Bay Area stores to stop carrying Ahava, skin-care products made in what she calls an illegal Israeli settlement in Palestine.

The BDS campaign is “a tried and true nonviolent tactic to get the Israeli government to uphold international law,” Abileah told me. “We decided to be in solidarity.”

But some Jewish leaders feel BDS goes too far.

“The term delegitimizing Israel refers to the intent to eliminate the Jewish and democratic State of Israel by portraying it as an illegitimate nation,” Kahn wrote in an email. “The boycott/divestment/sanctions movement’s leadership has made clear that this is their ultimate agenda and one of the movement’s explicit objectives would achieve that aim resulting in a dire threat to nearly half of the world’s Jewish population that lives in Israel.”

BDS is mentioned several times in the Federation funding guidelines, and stands out as the only specific example of what it means to “undermine the legitimacy of the state of Israel.”

ISOLATE THE EXTREMISTS

But organizations like the Federation and the JCRC aren’t the only ones interested in the path that Israel-Palestine discourse among Bay Area Jews takes. The Reut Institute, a think tank based in Tel Aviv, “has been committed to responding to the assault on Israel’s legitimacy since 2008,” according to the introduction to its 2011 report: “San Francisco as a Delegitimization Hub.”

The report ranks San Francisco and London among the “few global hubs of delegitimization.” It also warns of the dangers of San Francisco in particular as top-delegitimizing city, noting “the role of the San Francisco Bay Area as a generator and driver of broader trends, or as a hub of social experiments…What won’t pass in San Francisco won’t pass anywhere else, and what happens in San Francisco doesn’t stay in San Francisco.'”

San Francisco gets this attention from Reut because of dissent within its Jewish community, which the institute calls globally unparalleled. “While in London delegitimization is being promoted primarily by groups that are not part of the Jewish community…an increasing number of Jews in the San Francisco Bay Area have become ‘agnostic’ towards Israel, and are fueling the delegitimization campaign.”

The report’s authors, Reut’s “national security team,” do not spend much time explaining what “delegitimizing Israel” means. When it does, BDS again stands out as one of the only concrete examples. According to the report, in the Bay Area “the number of individuals who are willing to stand up for Israel is declining while others have been fueling the delegitimization campaign, many times unintentionally, by engaging in acts of delegitimization — namely, actions or campaigns framed by their initiators as a reaction to a specific Israeli policy, which in practice aim to undermine Israel’s political and moral foundations. Examples include support for the BDS movement and the 2010 Gaza Flotilla,” a protest in which ships full of supporters and cargo tried to make it to Palestinian land in violation of an Israeli embargo.

The report labels those looking to delegitimize Israel “extremists.” It warns, however, that those questioning Israel’s policies, when rebuked by its “tradition defenders,” may be swayed into trusting the extremists. It therefore advocates a “broad tent approach,” advising that Jews in the Bay Area initiate a “community-wide deliberation” with an “aim to…drive a wedge between the extremists and those who principally support the legitimacy of Israel’s existence regardless of policy agreements.”

It’s important, according to the report, to make sure that supporters of BDS are seen as “extremists.” The “broad tent” is supposed to contain all Jews, with a diversity of opinions — except those supporting BDS and other acts of “delegitimization.” In light of this goal, the report praises the Federation’s funding guidelines and the Year of Civil Discourse.

“Through the funding guidelines drafted by a JCRC-JCF Working Group…the San Francisco Bay Area has set the standard nationally as the first American Jewish community to develop guidelines delineating red lines that go hand-in-hand with the broad tent approach,” Reut reports. “Additionally, we regard the Year of Civil Discourse…led by the JCRC, as important best practices that could be emulated in other places.”

ORTHODOXY

The Bay Area’s left-leaning Jewish organizations may be influential, but under such a hot spotlight, they tread carefully. Congregation Sha’ar Zahav is one such organization. Last year, the synagogue surveyed its members to test opinions on Israel.

“In general, the survey shows that we have a liberal left-leaning congregation,” said Terry Fletcher, a member of Sha’ar Zahav who now heads a committee created to follow up on the survey results. “People tend to blame, shall we say, both sides of the conflict, both Israelis and Palestinians, somewhat equally.”

Fletcher’s committee has organized events and discussions in the wake of the survey since January. “One idea was that we would start with something non-controversial,” Fletcher told me. “But we couldn’t think of anything that everyone on the committee considers non-controversial.”

The programming has featured discussions on evolving relationships with Israel and questioned their nuances. But Fletcher says they haven’t been able to venture into BDS territory.

“I would love it if we could get to a place where we could actually address that,” Fletcher reflected. “And we would want to do it from a balanced perspective. But it’s such an emotional issue.”

There are practical concerns as well. According to Fletcher, the Federation gives a small amount of funding for scholarships for Sha’ar Zahav’s religious school. The money that funded Fletcher’s committee’s programming came from Sha’ar Zahav’s general fund, when there was enough of it. She says that the committee is now operating without a budget due to tight finances. Even so, if the committee’s programming were to breech the Federation’s funding guidelines, it might put the program in jeopardy.

“To me, that’s what’s so problematic about these guidelines,” Fletcher said. “The guidelines are saying, if you want money from us, we have restrictions on what your organization can do. Even though our programming is not funded by the Federation, because it funds something completely unrelated, it could get cut.”

Fletcher also questions that paradigm of “delegitimizing Israel.”

“I think this is a term that people who defend Israel use to label people who criticize Israel in a certain way,” she said. “Many of us would answer that it’s Israel’s own policies that are delegitimizing Israel in the eyes of the world. I don’t find it a useful term.”

Sha’ar Zahav will be hosting the Reclaiming Jewish Activism panel. Davey Shlasko, a member of the congregation who helped facilitate the new arrangement, thinks the concern about Abileah’s associations were misplaced.

“I think it is unfortunate that the predicted objection to Rae’s other work was enough of a concern to cancel an event that is actually about drawing inspiration from our ancestors,” Shlasko told me via email.

But it’s in looking back at history that the panel acquires so much meaning. “It is safe to say that living in the United States, Jews have never been more empowered, safe, and connected to the community they live in,” mused one source, who wished to remain anonymous. “It is inevitable that with such success, the need to band together changed. The group identity changes. Sometimes it’s that fight, that need to rally together, that keeps the group intact.”

For Abileah, “the event will be Jewish activists talking about our ancestors.” She’s upset about the event’s cancellation, but not surprised.

“For a lot of Jewish people it can be challenging to speak out against this issue because you don’t know where your friends stand on this, or your synagogue or even your family,” she said. “There are a lot of people who we say are PEP: progressive except Palestine. My family and community have been supportive, but I’ve gotten hate mail and threats of violence.”

“It sounds like these Jewish institutions that are censoring have so much power, like they’re the mainstream Jewish voice. But I think the majority of Jewish Americans want a resolution to the conflict and are opposed to the occupation,” she said.

And how does she think Joseph Abileah would react to this situation? “I’d like to think that he would be shocked and hurt by it,” she said. “It’s sad to see so much fracture in the Jewish community over this issue.”