arts@sfbg.com

THEATER The Berkeley Rep’s thrust stage sinks to floor-level down front where a simply furnished living room freely communicates with the audience seated nearby, while to the back rises the imposing façade of San Francisco City Hall. The impressive jumble of a set (by Todd Rosenthal) ensures the jarring conflation of private and public life strikes us palpably before a single line is uttered in Ghost Light. As it happens, the first words are those famous ones spoken by Dianne Feinstein from City Hall on November 27, 1978, announcing the assassination of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk by former supervisor Dan White. They come over the television to a 14-year-old boy (Tyler James Myers) home sick from school the day his father died.

The dream play that follows is not realistic, but it is also more than fiction. A unique collaboration between Bay Area–based director and California Shakespeare Theater artistic director Jon Moscone (real-life youngest son of the slain mayor) and Berkeley Rep’s Tony Taccone, Ghost Light is an at times promising but otherwise laden attempt to explore the stifled grief of a man haunted by the death of a murdered father — a father who was also a public figure, a political leader whose legacy is in some sense embattled (or at least seriously overshadowed by the subsequent apotheosis of Harvey Milk).

The complex feelings this entails for the son of such a man — whose career in the state senate and as mayor was arguably more important than Milk’s to the legal and social battle for gay rights — are only heightened by the fact that the son is also gay, with a public profile of his own and the mixed blessing of a prominent family name.

If the son in this situation-turned-scenario sounds a little like Hamlet, the comparison was not lost on Taccone either, who penned the script while drawing on hours of freewheeling conversations with Jon Moscone, initiator of the project and the play’s director. (Ghost Light had its world premiere last year in Ashland at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, where it was commissioned as part of its “American Revolutions: The United States History Cycle.”) Director-turned-playwright Taccone has the character “Jon” (played with manic energy and sudden introspection by a sympathetic Christopher Liam Moore) stuck midway through the preparations for a production of Hamlet, unable to decide what to do with the Ghost — indeed, haunted by the whole idea. This unusual block has his best friend and collaborator Louise (a lively if slightly affected Robynn Rodriguez) frustrated and worried.

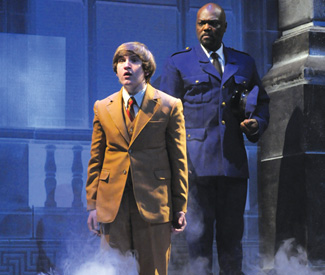

Jon’s block also feeds a dream life populated by several characters — a Loverboy (Danforth Comins) spun from an online flirtation; his perennially 14-year-old self (Myers) locked in a battle of wills with some cosmic undertaker cum grief councilor named Mister (a sure, larger-than-life Peter Macon); the silent image of his black-veiled widow mother (Sarita Ocón); and a menacing prison guard in a soiled shirt (a sharp Bill Geisslinger), who turns out to be the grandfather he never knew.

It’s suggested more than once in the dialogue that all of these characters stalking his sleep (and often arriving onstage through the portal of Jon’s bed, pitch atop the shiny black granite steps of City Hall) are merely the dreamer himself in various disguises and aspects. This much, of course, we are already primed to assume. In fact, the fundamental problem facing the main character — namely, his inability to properly let go of his own grief and suffering around the death of his father, which appears here as an inability to let his own father’s “perturbed spirit” rest at last — is equally a condition readily recognizable to a modern audience in a therapeutic age. It may be grounds to build on in terms of character development, but the lack of mystery here also undercuts any suspense in the plot, as the increasingly blurred line between Jon’s dreaming and waking lives points toward nervous collapse and the threat of some self-inflicted disaster (personified by the foul-mouthed, homophobic, and gun-toting prison guard stalking his unconscious).

Taccone makes a valiant attempt to draw together a complicated and wrenchingly personal yet all-too-public story with a set of interrelated subplots and quick-moving dialogue (filled with as much quippy humor and menace as pathos). But the results are uneven. Although Geisslinger makes a serviceable villain, the danger he represents never feels palpable. Likewise, the underworld subplot involving boyhood Jon (played a little too typically “boyishly” by Myers to be readily believed) comes across as vague and treacly.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is the more realistic, down-to-earth scenes that play best and are most evocative. The intricacy of a life divided painfully between public and private personas, public and private pain and loyalties too, comes across best when the character of Jon is operating in the “real” world. To this end, Moscone the director shrewdly brings the audience in at key points as well, raising the houselights for an acting master class led by his onstage character. Meta-theater, town hall meeting, group therapy — the lines begin to blur here in a lively, resonant discussion of “acting” as social action.

Another interesting scene takes place in a bar, where Jon finally meets Basil (Ted Deasy), the man with whom he’s been having an online fling for weeks (and the inspiration for the Loverboy of his increasingly intrusive dream world). The awkwardness, defensiveness, and barely contained rage revealed here — as Jon discovers that Basil’s own fantasy projection incorporates his public familial tragedy — speak more eloquently to the messy particulars of the main character’s dilemma then perhaps any other scene in the play.

In the end, the thematic aptness of the mise-en-scène — which forces Jon, for instance, to open the front doors of City Hall just to retrieve a beer from the fridge — speaks also to the monumental task this play has set itself. If the results prove very mixed, they are all the more discomfiting because the root story is so fascinating, the dramatic project itself audacious and strange, and the insight to be potentially gleaned so tantalizing — speaking to our collective intersections with history in the deepest recesses of the psyche.

GHOST LIGHT

Through Feb. 19

Tues., Thurs.-Sat., 8 p.m. (also Sat. and Feb. 16, 2 p.m.); Wed. and Sun., 7 p.m. (also Sun., 2 p.m.), $14.50-$73

Berkeley Repertory Theatre, Thrust Stage, 2025 Addison, Berk.

(510) 647-2949