By J.H. Tompkins

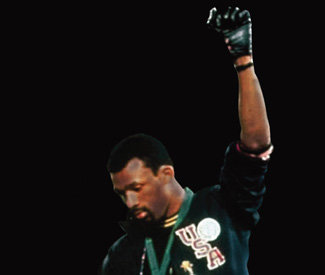

LIT On October 16, 1968, in Mexico City, American Olympic sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos electrified the world by accepting their medals with heads down and gloved fists thrust proudly in the air. Their defiance provided a fitting end for a year that began with Czechoslovakia’s Prague Spring and America’s military humiliation during the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, and saw the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and its explosive aftermath, the general strike in France, the riveting presence and influence of the Black Panther Party, mushrooming opposition to the draft, and rioting in Chicago during the Democratic Convention.

Like Mohammed Ali, who in 1967 went to prison rather than fight in Vietnam, Smith and Carlos wrote an important page in American history. Like Ali, they have remained true to the principles they embodied years ago. Now, 43 years down the road, it’s hard to find anyone to speak against what they did.

But at the time, precisely because their enemy was weakened by exposure and their supporters inspired, they faced a blistering backlash. They were banished from Olympic Village, and sent back to the United States. Their crime? Smith and Carlos were allegedly guilty of tarnishing the spirit of an Olympic games that were supposed to be above and beyond politics.

Author-columnist-cultural critic Dave Zirin, who with Carlos has just published “The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World,” has more than a few things to say about the sanctity of sports and the way political context shapes athletes as well as the games they play. These days, a conversation with Zirin has a special quality: not only has he written a book that sheds new light on an important, long-ago event, the present moment is energized by political turmoil that brings to mind the 1960s.

“I was an absolute sports junkie in the ’90s, when I was in college,” Zirin told me in a recent interview. “I memorized stats, followed every sport, it was my oxygen. I didn’t follow politics, much less politics in sports, until something happened that stopped me cold: In 1996 [Denver Nuggets guard] Mahmoud Abdul Rauf made a decision not to stand during the National Anthem. He was asked whether he understood that the flag was a symbol of freedom and equality throughout the world, and he said it may be to some, but to others it’s a symbol of oppression and tyranny. This was before the spread of the Internet, and Rauf’s stand was only covered by the mainstream media. They crushed him.”

Zirin realized then that there was an aspect of sports history he hadn’t concerned himself with, “the place where social justice and sports intersect,” as he put it. It has shaped the work he’s done since.

Among many other things, Zirin writes a column, “Edge of Sports” for the Sports Illustrated Website, has a weekly radio show called “Edge of Sports Radio” on XM, and contributes regularly to The Nation and SLAM Magazine. Along with “The John Carlos Story,” he was written books including “What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States,” “Welcome to the Terrordome: The Pain, Politics, and Promise of Sports,” and “A People’s History of Sports in the United States.”

As Zirin and Carlos point out in the book, the futures of both runners were shaped by what they did in Mexico City. They struggled to find jobs, stability, and peace of mind. Still, Zirin writes “Unlike other 1960s iconography — Woodstock, Abbie Hoffman, Richard Nixon — the moment doesn’t feel musty. It still packs a wallop.”

It resonates because the injustices they protested are still rife in America, and because the arena in which they took their stand — sports — creates common ground for so many people.

“I don’t think there’s any place where the contradictions in American society are on such sharp display as in sports,” Zirin told me. “Think back to African American boxing champions Jack Johnson and Joe Louis. Neither made explicit political statements, but they had representative political power, representing power and pride in the context of racism and white supremacy. They weren’t just entertainers but in fact their presence, the inspiration they provided, was a threat to the established order of things.”

In sports today, there’s no doubt that athletes, in particular African American athletes, play a similar role. NBA hall of famer Charles Barkley once objected — perhaps with his tongue somewhat in his cheek — to the idea that he was a role model. Zirin laughed at the mention of this, saying, “Yeah, and the sky isn’t blue. You don’t chose to be a role model, you are one. It’s an objective thing. And if people are going to be role models, like it or not, then we all have to examine what they’re modeling. If you believe that the fact that a player can dunk makes him a great person, that says one thing. If having a sense of purpose in politics is important, then that says something very different.”

When Zirin and Carlos planned their book, both agreed that they weren’t interested in producing a sports memoir. “We didn’t want to say ‘look at me, genuflect at my athletic greatness.’ We wanted to say that not everyone can run at a world-class speed, but anyone can live a life dedicated to a sense of purpose.”

That approach runs head-on into a mainstream media that has made a point of emphasizing how “today’s pampered athletes,” as the media often put it, want nothing more than a fat pay check. There’s truth in this perspective — although it should be noted that both the NFL and NBA have experienced lockouts this year and that the same media outlets rarely describe the fabulously wealthy owners of professional franchises as pampered billionaires.

“I wrote an article,” he explained, called “‘NBA Players: Welcome to the 99%.’ Despite their money and privilege, they found themselves in a position where they were facing arrogant billionaires asking for a bailout because they made a lot of bad business decisions as NBA owners. It’s just like Wall Street bankers want American working people to cover all their bad bets. Will their proposed savings go back to fans? I don’t think so, they’ll just get a bigger slice of the pie.”

Besides, Zirin pointed out that there’s a lot more to the story that rarely reaches the public. Professional sports will publicly punish athletes who are caught crossing certain lines. But when it comes to speaking to the politics of injustice, the leagues try to deal with transgressions behind the scenes.

“There’s a ton of corporate and financial pressure on these athletes,” he says. “And these players talk to each other about guys like Craig Hodges [a guard on three Chicago Bulls championship teams], who in 1992 passed a note to Bush Sr. about Iraq War I when the Bulls visited the White House. He was drummed out of the league for that and these stories are passed down almost like scare stories. At the end of the day, we have to remember what Carlos and Smith did was in the context of global revolt and crisis. It was a symbol of the moment and a perfect merging of movements and moments. We can’t forget that.”

Although Zirin makes a point in his work to include athletes of all nationalities and sexual preferences, he has particular insights into the role African American athletes play in American culture.

“John Thompson says that Black athletes have the blessing of the burden of representation,” he noted. “It’s a burden because if one athlete does something, then it’s an issue for all Black athletes to deal with, for instance Michael Vick’s involvement with dog fighting. It’s not Peyton Manning’s problem that Chris Herron [a white one-time basketball standout from the mid-2000s] got on drugs. It works in a different way for Black athletes. The blessing part is the you’re part of a tradition, you stand on the shoulders of men and women like Jim Brown, Bill Russell, Wyomia Tyus, and Mohammed Ali, and you have an ownership of that tradition. It’s true that Steve Nash and all athletes are part of the tradition, but it runs more seamlessly through the African American community.”

These days, the sports world is talking about another scandal, this time the ugly situation at Penn State. Zirin discusses those problems in the context of a bankrupt culture, where the NCAA — the self-proclaimed moral arbiter of college sports — refuses to speak to hypocrisy that links all the problems in order to ensure its own survival.

Sooner or later, he said, the NCAA will either sink beneath its own corrupt weight, or athletes — who because of the professionalization of youth sports know each other in many cases from their early teens — band together and demand some compensation for the money that they generate. College presidents are the loudest complainers and the most important enablers.”