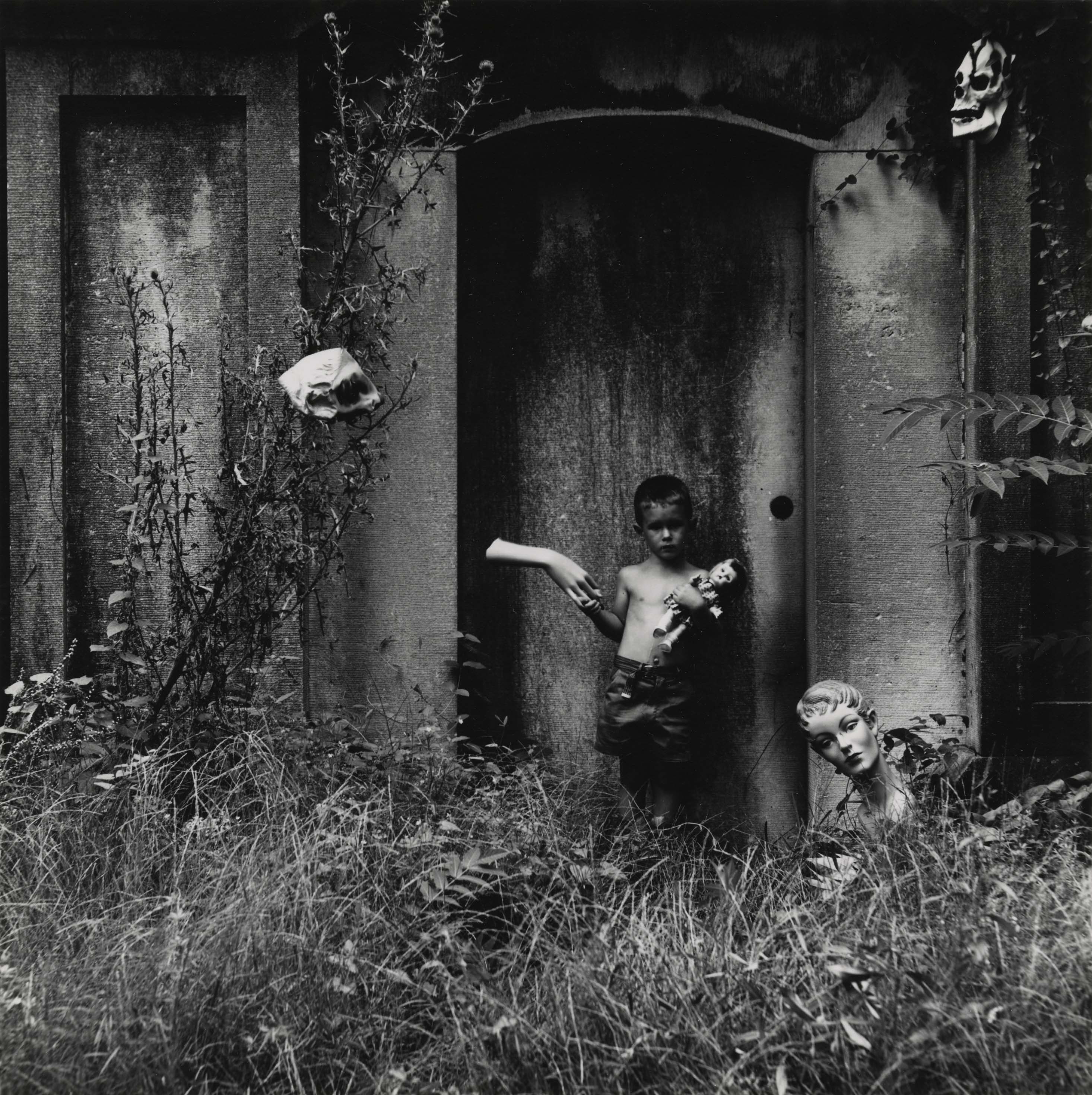

Photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925-1972) is an anomaly. There’s little consensus about the nature of his work beyond its unusualness. Throughout the late 1950s and 60s, Meatyard drove his wife and kids to dilapidated farm houses outside Lexington, Kent., where he used them as models for his photographs. He adorned them with cheap masks and accessorized the settings with broken mannequins, mutilated dolls, and other props that he would obtain from thrift shops and junkyards. He ultimately created a series of heavily shadowed, black and white photos that are chilling (but sentimental), surreal (but in an everyday sort of way), and at times, plain weird (I guess?)

Needless to say, the series is not an obvious one. “Ralph Eugene Meatyard: Dolls and Masks,” now showing at the de Young through February, collects 60 of the photos from that period — all of them not much larger than a CD case. But even the museum is ambivalent about explaining the work to visitors. They refer to quotes from Meatyard and have them by certain photos hoping they might shed some light. They mention, for instance, how Meatyard cited Zen Buddhism as an influence, and that he turned the idea of the family photo on it’s head. In truth, though, Meatyard was notoriously silent about how his work should be viewed. Guy Davenport, a close friend of Meatyard’s, said in the nine years he knew Meatyard, his friend said relatively little about his work: “He never instructed one how to see, or how to interpret the pictures, or what he might have intended.” Virtually all of the photographs in “Dolls and Masks” are untitled, too, which certainly makes the tour guide’s job difficult. “I will try my best to answer your questions,” I heard one guide say, overcome.

However, one influence that’s often mentioned and that does seem to ring true about Meatyard’s work is literature. Meatyard was a devoted reader (he even read while driving), had an immense library, and walked in the same circles as writers and poets; it seems, to a certain extent, the reason why it’s difficult to narrow down what the photos in “Dolls and Masks” are doing is because they aren’t necessarily exploring a theme, an idea, posing a question, or trying to evoke a particular sensation or response. Rather, Meatyard imagined an entire world with these photos as though he’d written a story, in the same way Lewis Carroll imagined a world in Alice in Wonderland and Franz Kafka evoked one in The Trial or The Castle. In Meatyard’s so-called world, it’s normal for people to be wearing hideous masks and wandering outside abandoned buildings with mutilated dolls; so that, in fact, the masks and props are secondary to understanding the work.

This makes the series as rich and elaborate as a novel, and it’s why it can be all the aforementioned things at once: chilling, surreal, sentimental, commonplace … etc. Collectively, they are like illustrations for an unwritten story, perhaps a children’s story. Occasion for Diriment, for instance, one of the few titled photos within “Dolls and Masks” that combines the words “Dire” and “Merriment” (something, of course, Carroll was known to do), shows two kids in the dark, one wearing a cartoonish mask, jumping up in the air and pounding their chests. The photo is not haunting, but instead, speaks to the spirit of childhood, like a scene out of Peter Pan. The same could be said of one of Meatyard’s more famous untitled photos, which shows a shirtless boy standing in a doorway and holding a mannaquin’s hand. It recalls the lost boys.

“I remember thinking that here was a photographer who might illustrate the ghost stories of Henry James,” Davenport wrote. Meatyard’s work suggests he could have illustrated James and more: Edgar Allen Poe, for instance, or even some poems by Samuel Coleridge (I’d appreciate an illustration of “The Devil’s Thoughts”). But Meatyard died of cancer in 1972 at the age of 46, shortly after the photos in “Dolls and Masks” were taken. And, as has always been the case with his photography, in life and posthumously, Meatyard will hold a relatively quiet and humble place in the museum.

“Ralph Eugene Meatyard: Dolls and Masks”

Through Feb. 26, 2012

de Young Museum

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Dr., Golden Gate Park, SF