All photos by Stephen Heraldo

Just beyond the scope of the perpetual debate of revitalizing Mid-Market — defined as the stretch from Fifth Street to Van Ness Avenue — an extraordinary project is quietly closing its doors on an oblique, no-man’s-land corner of Market near Franklin. There, for one hundred days and nights, an empty glass storefront opened up to spill a swath of light and music onto the cigarette-studded sidewalk — without funding, a business model, or (as founders Will Greene and Sam Haynor are the first to say) much of anything else.

“Ask us our mission statement,” One Hundred Days of Spring organizer Haynor challenges.

“We don’t have one,” Greene, his creative partner, cuts in.

“Well, yes we do,” says Haynor.

“Yeah, that not doing it seemed like a cop-out,” the pair concludes.

“It” was creating more than three months of free and donation-based events, classes, and recorded stories representing a variegated slice of the local population: hipster kids in art collectives, professionals on their Market Street commutes, and low income neighborhood residents, including many who bed down each night on the block.

As part of Central Market Partnership’s ongoing efforts to inject arts and culture into revitalization plans for mid-Market, the San Francisco Office of Economic and Workforce Development is joining with the Arts Commission to hold a series of focus groups exploring ways to engage artists, small businesses and cultural organizations in the making of a thriving creative district.

Five focus groups have already met, according to OEWD’s Jordan Klein, and over the coming weeks, more gatherings — of community residents, transportation advocates, historical preservation advocates, and nonprofit leaders — will provide insight for the Central Market Economic Strategy, to be released in the late summer or early fall.

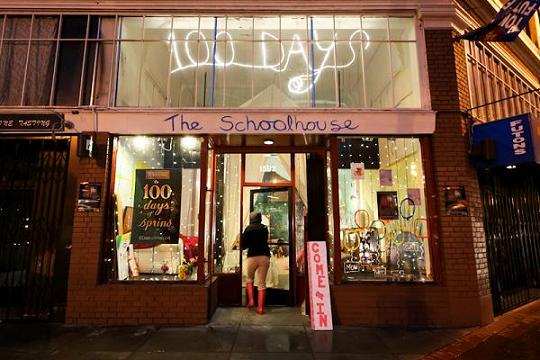

One Hundred Days of Spring wasn’t on the agenda of any of these meetings. A former boutique clothing store sandwiched between SROs and auto body shops on a strip shadowed by the sheer, block-long face of a Honda dealership, the space’s previous tenants didn’t last long. But transformed into a gypsy-tent-circus-wagon-theater-gallery-cum-classroom, the storefront, reborn as the Schoolhouse, rooted itself in the neighborhood in just a few months.

The hundred days are now over. But if the packed closing ceremony was any indication, Haynor and Greene’s model is one that the community is keen to reproduce. Mark Singer, a research librarian and freelance writer who found the project in what the two founders call the “analog way” — by stumbling across the threshold — told supporters, “I challenge everyone in this room to replicate what we’ve seen here, seen in the last hundred days.”

“The ultimate goal,” Haynor said, “is not only to share and to educate, but at the end of one hundred days, to have created one hundred new ideas for people to carry out into the world.”

Nothing to it

One Hundred Days of Spring was an experiment in community-supported programming. Rather than relying on or waiting for grant money, Haynor and Greene hoped to show that a community space can be self-sustaining — for the benefit of those who can contribute more and those who must contribute less.

“San Francisco is grant rich,” Haynor explains, “but it’s also full of people waiting for grants. They have a bunch of awesome ideas, but by the time the grant cycle comes around, the initial spark is gone. For us, going after a grant would just eat up time, and we wouldn’t end up doing what we wanted.”

Instead, the two 25-year-olds pooled their savings and paid $2,000 a month for rent from March to June, $200 for utilities, plus a few hundred extra for renovations and insurance. Within three weeks of the initial idea, they had moved into the space and populated a calendar of events through friends, friends of friends, and tools like SF Chalkboard. They were running full tilt by day six.

In just over three months, the team offered more than 250 classes, shows, and tutorials — sometimes five in a day — covering everything from truffle-making and fermentation to bike repairs, aerial silks, and open mics. By collecting donations on a pay-what-you-can basis, Haynor and Greene were able to recover a large portion of their initial output, and also garner an extra $4,000 to reinvest into the project.

Greene on the value of 100 days of events: “If you try to put a value on what we have now, that we didn’t have then, you couldn’t buy it for $4,000.”

Though the Schoolhouse founders ended up $4,000 short, Greene says they “could have broken even” if they had focused more on the project’s revenue-generating components, like filming videos for musicians who performed in the space.

Even so, for Greene the worth of One Hundred Days of Spring was indisputable. “If you try to put a value on what we have now, that we didn’t have then, you couldn’t buy it for $4,000,” he says.

When Judy Nemzoff, community arts and education program director for the Arts Commission, stopped by the Schoolhouse and asked how Haynor and Greene did what they did, the two replied, “Well, we just signed a lease.”

It takes two

Inside the Schoolhouse, the laid-back attitude seemed to likewise shrug “nothing to it but to do it.” But the warm, easy atmosphere belied the late nights and hard work it took to get ‘er done.

Understanding how One Hundred Days of Spring came to be — and why it worked so well — means understanding a bit about its creators

Greene and Haynor, hanging at the Schoolhouse

Haynor and Greene have the kind of friendship people make movies about. Besides the sort-of charming things like finishing each other’s sentences and bragging about accomplishments each knows the other would never mention for himself, there’s the sense that somehow, these two unassuming fellows are going to change the world.

“We’re a good balance,” Greene says. With the air of someone showing how two-plus-two equals four, he explains, “Sam’s a bit spastic, and I can plunge a toilet.”

“We have different skill sets, but we share goals,” he continues. “We keep each other in check. We’re both very often wrong, but we’re rarely both wrong at the same time.”

Coco Spencer, who joined One Hundred Days of Spring as an intern partway through and become an indispensible team member, says she was willing to dedicate so many hours to the Schoolhouse because, “Basically, Sam and Will are the most inspiring people I’ve ever met.”

Haynor and Greene were campers and later counselors together at the Bar 717 Ranch in Trinity County. There, they found each other, and also a passion for teaching — or, as they put it, “helping people to be good versions of themselves.”

Though each has traveled and embarked on sundry individual projects — Greene as a musician and videographer, Haynor as a chess champion and conflict-area journalist — they continue to connect over their drive to educate in unique new ways.

Bathroom, beats, and big ideas

At the Schoolhouse, that meant engaging community members through a service-based approach. “Our main goal is to provide resources to people who need resources,” Greene says. “We’re not interested in providing resources to people who have resources.”

Given the diversity of The Schoolhouse’s participants, “resources” could mean different things.

Haynor explains, “For some people, we’re a bathroom. For some we’re a place to stop in and say ‘hi.’ For some, we’re a place to do events.”

“We’re successful because we’re always doing something fun, and everyone feels invited,” Greene says. “It’s the loose nature of our project. There’s no doorman, no guy with a cash box.”

There were challenges (“Sam’s been trying to put together homeless poetry readings, but he’s scheduled them for the first of the month. That’s when everyone gets their checks, so everyone gets drunk,” Greene says at one point), but there were also many moments — like when a woman from the block walked up and started giving Haynor a massage, or when Greene calmly negotiated with a rowdy, intoxicated visitor, encouraging her to pipe down and eventually leave — that pointed to a deft interface with the surrounding community.

“They respect our storefront more than they do the others,” Greene says. Some locals worked shifts at the Schoolhouse in return for resources. Others stopped in for music, for food and nutrition classes, or to look at the art. Some simply came by to talk about living in the area.

During an “Un-Talent Show”, a performer named SofT humorously described a street-dweller’s perpetual problem: carrying belongings. He showed an in-stitches audience how to bundle objects in an old sweater — a wholly relatable rap on wrapping. Another visit came from Benny, one of SF’s famous itinerant tamale sellers, who lives in an SRO across the street and makes what partakers described as “possibly the world’s best tamales” across town in his girlfriend’s kitchen.

Haynor describes a woman who walked into a sewing workshop — run by SF Social Fabric, a volunteer-staffed bike maintenance and sewing skills collective — with “some trepidation.”

“She was in a room with a bunch of people who were nothing like her,” he says, “but we got to know each other over the fact that we all wear clothes. And they all fall apart.”

Neighborhood connections at the Schoolhouse

“There’s a duality to this corner,” Haynor says. “From doctors to the people who live on the block to all the people in the middle who travel Market Street. Before us, some wouldn’t even cross the street.”

“At our best,” he continues, “we’re a place people from another demographic can discover the old-fashioned way — with their eyes and their feet. They cross the threshold, ask what we’re doing, decide to stay, and learn something. Now, I can’t go five minutes without seeing someone I know, or someone who I recognize, or someone who just popped in.”

Singer, a perfect example of the phenomenon, started stopping by between two and five times a week after his initial discovery. He framed the project’s importance in simpler terms: “This is where we need these things to happen. Where it smells like urine on a hot day.”

Let’s put on a show!

Singer believes that projects like the Schoolhouse can “transform parts of San Francisco” by providing services that are more than “just artists and gallery-talk.” The Schoolhouse, he says, “was something visceral.”

“One Hundred Days of Spring created an infinite possibility for community that can’t be replicated on a screen or keyboard. We’re not talking Internet cafés with white earbuds, but humans breathing in the same space — collaborating, communicating in one room, and that room changing every darn day.”

Indeed, the walls of the Schoolhouse were repainted so many times over the course of the hundred days — with layers of murals, street art, installations, white space for projecting films — that Spencer, who took charge of many of the events’ logistics, joked she was hoping to reduce the interior square footage, and thus, the rent.

The zealous energy required to transform the space again and again was reminiscent — Singer pointed out — of Babes-in-Arms-era Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland exclaiming Hey, kids! Let’s put on a show in this old barn! That down-home, DIY energy may be just what efforts like the Mid-Market revitalization require.

Greene, who attended one of the Central Market Partnership’s focus groups, says the consensus was that knowledge about and access to space were the biggest obstacles to creating and executing programs of any kind.

“People are looking for answers,” he says, “looking for some larger entity to hand them space, or looking tax breaks. There’s the feeling that you can’t just do what you want to do.”

“Rather than saying ‘if you give us space, we’ll fill it with beautiful things,’ you can say ‘I’m just going to do it.’ If you’re willing to make it happen, if you work really hard, if you work with the people you’re trying to reach, then you don’t have to worry about anything else.”

Despite the waiting, wanting, hoping attitudes Greene says he encountered, he points out that plenty of others are “just doing it.” The Schoolhouse helped along a few such visionaries by sponsoring two “Grant Prix Dinners.” During the informal roundtables, entrepreneurs presented project ideas between courses. Participants paid a fee for dinner and a ballot on which to elect their favorite projects – to whom the entry frees were turned over as seed money at the end of the night.

Bringing together the neighborhood

At times, especially in San Francisco and other urban areas where real estate is costly, amping up a neighborhood’s arts and cultural amenities has acted as a roundabout measure to invite the type of gentrification that sweeps streets clean. That kind of programming is not intended to serve current residents so much as to usher in new ones.

By contrast, the Schoolhouse made a conscious decision to serve the neighborhood’s existing population — with safer-feeling streets resulting, and much more quickly, at that.

One Hundred Days of Spring was a bold, direct move to engage the local community. As such, it was highly effective not only at providing needed resources, but at tempering the less-desirable qualities of the neighborhood by creating a sense of community and responsibility among residents and passers-through.

“Coming out of Muni, walking home on Market Street,” Singer had said, “can frankly be pretty scary. There’s substance abuse, drug deals, and people who may or may not be harmless.” The Schoolhouse, he said, helped diffuse that lack of ownership and feeling of “anything goes.” For Singer – and Schoolhouse denizens of all backgrounds — the space managed to help tie a few new knots.

“The Schoolhouse brought me closer to a world that’s very marginal,” Singer said. “the homeless world.”

Whether or not Mid-Market planners will look to the Schoolhouse for a lesson in effective community building, the project’s two masterminds have undoubtedly developed a model they can draw on in the future.

Haynor and Greene plan to continue working together on community education projects. With One Hundred Days of Spring under their belts, they will be able to approach supporters “not just with an idea, but with a proven concept.”

“We are both in this together to see what we’re both capable of,” Haynor said. “To see if we’re any good at this thing.”

In the style of banter so typical of the pair, Greene added, “So we can figure out the rest of what we’re going to do with our whole darn lives.”