arts@sfbg.com

LIT Perhaps the biggest faux pas in critical art writing is using the artist’s first name when addressing his or her work. Countless teachers, critics, and editors have embedded this notion deep into the recesses of the right side of my brain. However, when writing this essay I continuously found myself wanting to address Mark Morrisroe only by Mark — as if I were having a personal conversation with him about his work. It could be that after spending a great deal of time with the artist’s recently published posthumous monograph Mark Morrisroe (JRP-Ringier, 512 pages, $65), that a bond, strong enough to diminish such formalities, seems to have formed between us. I feel as if we would have been the best of friends had Mark survived his untimely death from AIDS in 1989.

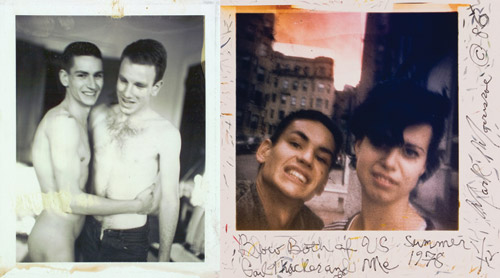

This mammoth publication spans the artist’s relatively short but undeniably influential oeuvre and includes 500 impeccably printed reproductions of his photographs, photograms, Polaroids, Super 8mm films, and signature “sandwich prints.” The resulting survey is nothing short of breathtaking. Mark’s dynamic approach to image-making is showcased alongside several poignant theoretical and explanatory essays reminiscent of Felix Gonzales-Torres’ retrospective monograph published by Nancy Spector and the Guggenheim Museum in 1995. As Gonzales-Torres would say, this is a book you would want to bring on leisurely day at the beach.

The monograph is divided into several sections, each encapsulating a portion of Morrisroe’s career and augmented with an essay detailing the importance of the specific subject matter in defining his artistic vision. I found myself spending countless hours examining each section and noting how Morrisroe’s hand is so vividly present throughout. Even in his most straightforward portraits, the notion of his human presence behind the camera — like so many other artists in the history of photography — is not lost. He is not simply producing likenesses of his subjects, he is simultaneously projecting reflections of himself onto the surface of the paper.

To be honest, I have yet to give the literary portion of the book its due diligence because I have been so blindingly seduced by the imagery. There is potential for this to happen to you as well, but keep in mind that the biographical knowledge available greatly informs the work and provides essential historical context that considerably heightens its cultural significance. I won’t go into too much detail of Morrisroe’s biography here because I feel that a few short sentences on the matter won’t do him justice. Besides, it would be far more entertaining for you to discover his story on your own among the pages of drag queens, hustlers, X-ray images, and vintage porn photo montages.

As a young photographic artist myself, I was struck most by Morrisroe’s visceral interest in understanding the alchemical processes of his chosen medium and the unflagging beauty of the individuals and peripheral culture he aligned himself with. Morrisroe’s photographs might be considered off-center — infused with the tumultuous happenings of his extraordinary life story. Yet the immediate sense of tragedy present within much of the work is lyrically transcended through his bold use of color and dreamlike, oftentimes surreal, and pictorial imagery.

Today Morrisroe’s palette could be read as reminiscent of the 1980s, a consciously busted queer-punk aesthetic. But it also serves as an elegiac reminder of dying analog photographic processes. (For those who aren’t photonerds: many of the techniques used by Morrisroe over the course of his career have become nearly extinct with the rise of digital technology and rapidly increasing cost of maintaining a strictly analog practice.)

The last section of the book features installation images from various solo exhibitions of Morrisroe’s work before and after his death. I can’t help but think of the myriad possible trajectories that would have been available had he survived the AIDS epidemic. It seems as if he was just beginning to come into his own and to fully understand his potential as a maker and progenitor of culture. Instead we are left with an impressive and spontaneous collection of work that was light-years ahead of its time. It seems appropriate that a monograph of this caliber would come to fruition now to allow a younger generation to connect with Mark’s spirit found in every lush-hued image.