The American economy’s worse now than at any time since the Great Depression — and whatever the Republicans say in Congress (and the president signs on to) the private sector alone can’t possible pull us out. The only reason we’re not at 1930s levels of unemployment is that we’ve had some modest federal stimulus money over the past two years.

But we’ve got this dilemma: Although every smart economist agrees that it will take more massive federal spending to turn things around, all we’re getting out of Washington is the worst kind of spending — tax cuts for the rich, which will cost $900 billion and do very little to help the economy.

Part of what’s going on — and Jerry Brown talked about it at his education summit — is that the public doesn’t trust government to spend their money wisely. Brown cited a poll saying that nearly half of Californians still think we can solve most of the budget problems in the state by getting rid of government waste.

The Pew Research Center has put together a couple of fascinating papers on attitudes toward the public sector, and they’re worth a rad. (Thanks, Gabriel Metcalf at SPUR for tipping me off about this.) The first one is called “How a different America responded to the Great Depression.” Researcher Jodie Allen’s conclusion:

Quite unlike today’s public, what Depression-era Americans wanted from their government was, on many counts, more not less. And despite their far more dire economic straits, they remained more optimistic than today’s public. Nor did average Americans then turn their ire upon their Groton-Harvard-educated president — this despite his failure, over his first term in office, to bring a swift end to their hardship. FDR had his detractors but these tended to be fellow members of the social and economic elite.

More:

The most striking difference between the 1930s and the present day is that, by the standards of today’s political parlance, average Americans of the mid-1930s revealed downright “socialistic” tendencies in many of their views about the proper role of government.

True, when asked to describe their political position, fewer than 2% of those surveyed were ready to describe themselves as “socialist” rather than as Republican, Democratic or independent. But by a lopsided margin of 54% to 34%, they expressed the opinion that if there were another depression (and fears of one were mounting), the government should follow the same spending pattern as FDR’s administration had followed before.

And, those surveyed said they supported Roosevelt, the architect of the New Deal’s expansive programs, over his 1936 Republican opponent, Alfred Landon by more than two-to-one (62%-30%).

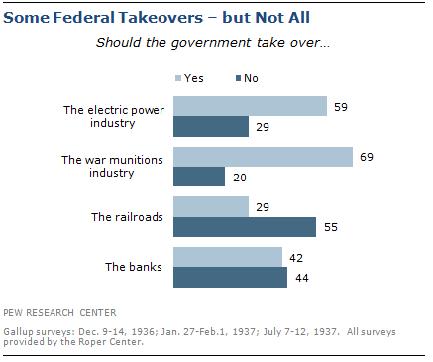

The charts are fascinating. A full 73 percent of Americans polled in 1936 thought government should provide free medical care to the poor. Sixty-four percent thought government should regulate and control war-time profits. In fact, 59 percent thought the government should take over the electric power industry and 69 percent favored nationalizing the wartime munitions industry.

And the people who were polled in these early surveys were overwhelmingly white, male and relatively well off. They were also socially conservative — 60 percent favored the death penalty and 67 percent wanted to deport all immigrants who were on public relief. Allen:

Is there a message in this for today’s America? Two possible lessons: First, it’s worth remembering that the social programs and banking controls that the New Deal era produced stood the nation in good stead over many decades of unprecedented prosperity. Second, Depression-era Americans’ faith in the country and its guiding institutions steeled them against the challenges of a double-dip recession and, years later, World War II. They had it worse, but they also expected it to get better, faster.

Compare that to a 1983 poll taken in the depth of the Reagan Recession, when 65 percent said that government had gone too far in regulating business, 62 percent rarely trusted the government in Washington and 78 percent opposed raising income taxes.

Fifty years, two generations, and the entire attitude of the American public toward government was turned on its head. It’s one of the fundamental dilemmas of American life, and one of the central reasons we’re in this mess.