Owen Ashworth is on the phone with me, explaining his decision to retire Casiotone for the Painfully Alone:

“Definitely something has changed in me the last six or seven months where I haven’t enjoyed a lot of the things about making music the way I had. I feel like I haven’t been as nice of a person as I’m used to being. For the sake of my sanity I need to stop for a while. It’s been an insane couple of months doing these last tours, emotionally draining in ways that I didn’t anticipate. So I’m just really looking forward to being done for a while and coming back to it when I’m excited to come back to it.”

He pauses briefly, and adds, “There are a handful of songs I’ve already written for the next album, and a lot of half-finished ideas, which is usually how I work, with a lot of small skeletons for songs floating around until I figure out what to do with them.”

If this seems like a glaring contradiction, remind yourself of one simple fact: musicians never retire. Even an attempt to do so is usually greeted by confusion and misunderstanding. Earlier this year Ted Leo had to address misquotes that made it seem like he was hanging up his guitar. When musicians make the claim outright, it usually turns out to be hot air, as is the case with Jay-Z, who in 2003 made leaving the rap game a frequent subject of interviews and lyrics, and was never heard from again.

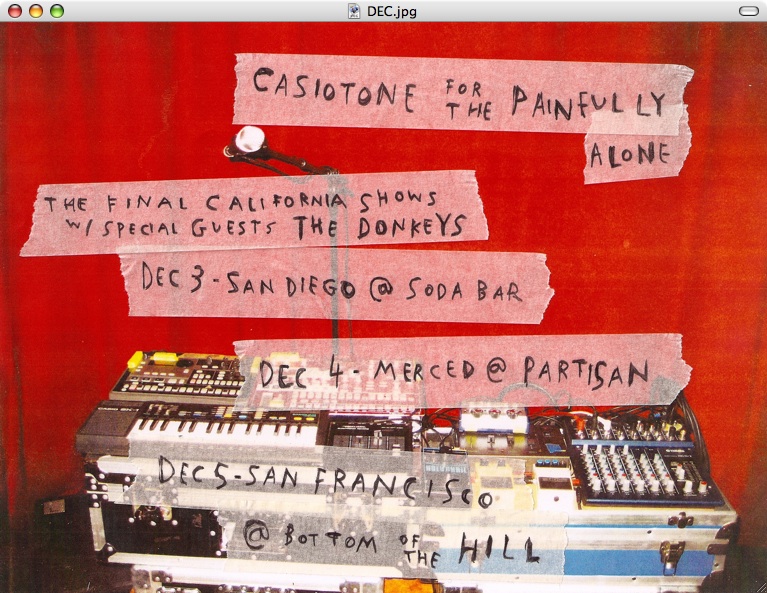

Ashworth isn’t oblivious. In September, he broke the relative silence of cftpaforever.livejournal.com/, usually reserved for tour info, to say, “I’d just like to clarify that this doesn’t mean that I’m quitting music. I love writing & recording songs, & I hope to make lots more records in my lifetime. But, after nearly thirteen years of being the dude from Casiotone for the Painfully Alone, I’m ready for a fresh start & a new challenge. So, after December 5, 2010 (the thirteen year anniversary of my first show), I’m throwing out the old songs & I’m trying something new. I’ll have more news about new projects & plans in the coming months.”

So far, Ashworth’s committed to the plan. On Sunday, Dec. 5, he’ll be back in the city where he started making music, for a final show as Casiotone for the Painfully Alone at Bottom of the Hill.

In a way it’s been a long time coming. Truth is, Owen Ashworth never intended to be Casiotone for the Painfully Alone at all. It was a much of a fluke as his first show in 1997, at a warehouse space at 17th and Capp. “I played that show at the request of a friend of mine who booked it. I had just made tapes and she liked the sound of the tape so she kind of tricked me — she made fliers without asking me to play the show. She thought I wouldn’t say no that way. So I played the show with the idea that this is probably never gonna happen again, I’m gonna get this over with. I remember that I was very nervous, very shaky. I had one keyboard through a really tiny amp.” The next week he had another show booked, under the name of the mixtape he had given his friend: Casiotone for the Painfully Alone.

“It was just the name of a tape I had given her. I didn’t realize it was going to refer to me, you know. Seriously, from the first show to when I decided to quit Casiotone, I considered changing the name the entire time, but having it already done, it seemed like so much work to try and call it someone else. I decided it didn’t really matter, it was just the name and it was kind of catchy and stupid enough for people to remember it. At least in the beginning it described the music pretty well.”

Arguably, the name has mattered. As descriptive as the name was, particularly in the early days, for Ashworth’s distinctive style of indie pop, with consumately pathetic lyrics layered on top of cheap keyboards and electronic samples, it prefigured an audience’s response. The press around each album has been centered around two poles.

First, how closely the music sticks to the sound of a suburban child’s first piano. With each Casiotone for the Painfully Alone album, there has been an incremental departure from the titular keyboard, adding in instruments and collaborators, particularly since 2006’s Etiquette (Tomlab). Ashworth, who in a typically self-effacing fashion describes Casiotone as “an insane, slow learning process, learning how to tour and write and record, doing all of these things and kind of just falling on my face in front of people for the last thirteen years,” sees the development of his instrumental side driving him in separate directions.

“The way I make music is kind of getting fragmented between recording and performance. I’ve been producing for a Chicago rapper, Serengeti, and that’s been my project over the summer. He has a new album coming out on anticon and it’s half stuff he did with me and half with Yoni from WHY? That’s sort of the more electronic side of the music. I enjoy recording that, but it’s not what I’m interested in doing live, so I think it works really well that I’ve been moving into production more. I can fuck with samplers and drum machines in my house and then just sort of give that music to other vocalists. Then for the music that I’ll be taking on the road and being accountable for and presenting over and over again in live settings, I’m more interested in playing with other people and real instruments.”

The Casiotone as an instrument may be easier to move past than the loneliness that Ashworth’s band name invokes and the lyrics bring to life. Simple, sad words that screw in as you listen, about regular people with typical lives. They’ve brought the musician a following, they’ve been his brand. But the association that the audience has for Ashworth and his emotional resonance has also been a nagging burden. “There’s generally a lot of assumption that I’m writing about myself, which is something that when I’m actually writing songs doesn’t occur to me much. I mean it’s fiction. Like any writer I’m inspired by real things that happen to me and my friends but it never occurs to me that it comes off as autobiographical.”

“With the name Casiotone for the Painfully Alone, the original idea was that the Painfully Alone was meant to refer to the listener and the idea of music as comfort music. It didn’t occur to me at the time that people would think that I was referring to myself as the painfully alone person.”

Casiotone records are galleries of character. A pedestrian world populated with eerily familiar people: high school teachers, Scrabble players, cellists, petty thieves, bedroom killers, landlords, and neighbors. Half of them you know by name. Half of them you’ve met before in real life. Sitting down to listen to a Casiotone record, you can relate to the situations. You’ve been in them, or know someone who has. The music engenders an emotional intimacy, it draws you in. “The way I make music is totally a tribute to the music I love and that claustrophobic, really intimate sense, I’m trying to create that because that’s a quality that I have an emotional reaction to in other music,” Owen says.

But the imagined intimacy that the fans has with the music, a sense of something real isn’t what drives Ashworth. “Genuineness isn’t even a factor to me. When I listen to Willie Nelson’s song “Crazy,” it doesn’t occur to me as, ‘Holy shit, Willie Nelson is going through the most intense stuff, I cant believe he’s singing about this.’ I think ‘That’s such a well-written song and he creates such a great atmosphere.’ I want to know how to write songs like that. I admire Willie Nelson as a songwriter, not as this survivor of all kinds of emotional problems.”

Ashworth has the remove of fiction writer for whom characters have there own will. When he talks about his characters, it’s not as a doting mother in whose eyes they can do no wrong, but as a friend who’s seen them make one too many mistakes. “I got really self conscious about what kind of people I was writing about, and I wanted them to start owning up to some of their own problems and take responsibility for the stupid things they did.” This culminated with 2009’s Vs. Children (Tomlab), an album he envisioned even before Etiquette as the end of Casiotone, with “a lot of more family-type relationships where people are having to consider their older relatives, having children and the young people they’re responsible for in their lives. I guess just showing more consequences of irresponsible living.”

It’s not uncommon for fiction writers to look back on old stories, and feel estranged, as if they were written by someone else. Ashworth has felt a similar distancing from his early work. “There are songs I wrote when I was twenty that don’t really mean the same thing to me as at the time that I wrote them. I feel like I’m covering those songs when people request them and it doesn’t feel relevant to me and I think that it would serve the material much better to be sort of left alone in the context of itself than for a man well into his thirties to continue performing these songs written by someone much younger.”

As Ashworth feels more alienated from his work over time, fans feel closer to it, and if they don’t, there’s always the potential for people to discover his early material for the first time, making it brand new all over again. (For better and worse.)

Of course, Ashworth’s not alone in the situation. All artists fight against their early successes, in an attempt to stay relevant, and practically, to stay financially above water. (Ashworth admits at one point, “Casiotone has been my source of income for a good while now and to cut off that source of income is a bit scary, but I can’t be proud of just doing this as a job, there’s gotta be more to it than that.”) For bands, this trend can result in fans demanding to hear “Free Bird” while they’re starting to intro “All I Can Do Is Write About It.” Eventually, almost everyone becomes a cover band of themselves, jamming at the County Fair or playing full albums for a new generation.

There’s always a break between artists and fans. The fans can romanticize the life, not seeing the physical and mental fatigue that can set in after playing the same material over and over, particularly when you damaged your hearing after too many nights being responsible for the full sound mix (as Ashworth has). They might not realize that the nostalgia for an old song never sets in when you play it every night. Or that, like an old marriage, the excitement is gone.

“It was really scary when I started Casiotone, and it felt so great to write a new song and be like ‘I have a new song I can play, my shows can be three minutes longer now.’ Whereas at this point, I feel like at my shows the priority for me is playing new material — [that’s] the stuff that I feel [is] most representative of me now, and that I’m most excited to share and excited to get better playing. But after thirteen years, there are so many songs that people want to hear I feel like I can’t get out of a show without playing — this list of songs that are expected as people;s favorites. I mean it’s super flattering and great,

but it’s really hard to move forward with new work when there’s this expectation for what you’ve done before.”

Ashworth already has an album in mind for the future, called Advance Base, the name of his studio, after the Antarctic meteorological station where Richard E. Byrd spent five months alone, even though it was built for three. Clearly, there are common themes and and interests that will persist in Ashworth’s music. But he’ll take his time and it won’t be under the exhausted banner of Casiotone.

“I’m killing Casiotone. I’m glad you enjoyed it, the records will be forever available, this is the new thing I’m gonna do now. I’m fully aware that there will probably be a smaller audience for the next thing I do. At the very least a different audience, and I’m sure there will be people who are super not on board with the idea that I’m not making what sounds like video game music anymore. That’s fine, and I’m glad Casiotone is still there for those people, but I’m gonna make myself crazy if I keep playing those songs for the rest of my life. I really love writing and recording songs and I just want to concentrate on continuing to do that. Just trotting out a greatest hits set for as long as I make music does not feel like a challenge.”

This may sound a little harsh for the tender-hearted lovers of Casiotone. But Sunday’s show, with accompaniment by the Donkeys and other SF musicians, is likely to be “a longer set, with some older songs I haven’t been playing that much lately. And just some stuff I don’t play usually.” So there you have it. Last chance. For now.

“I’m welcoming the chance to miss those songs.”