EDITORIAL Gigantic international sporting events tend to be great fun for the people who attend. They make great promotional videos for the host city. They can generate big revenue and profits for some private businesses.

But when the party’s over and the bills come due, these extravaganzas aren’t always a boon to the municipal treasury. And at a time when San Francisco can’t afford to pay for teachers and nurses and recreation directors, the supervisors ought to be giving much greater scrutiny to the deal that could bring the America’s Cup yacht races to the bay.

In 2009, as the city of Chicago was preparing an unsuccessful bid for the 2016 Olympics, the Chicago Tribune took a look at what the 1996 games had meant to another U.S. city, Atlanta. The Trib’s conclusion: lots of private outfits and big institutions did well — the Atlanta Braves got a new baseball stadium and the Georgia Institute of Techology got a new swimming and diving center — but the city itself didn’t get much money at all.

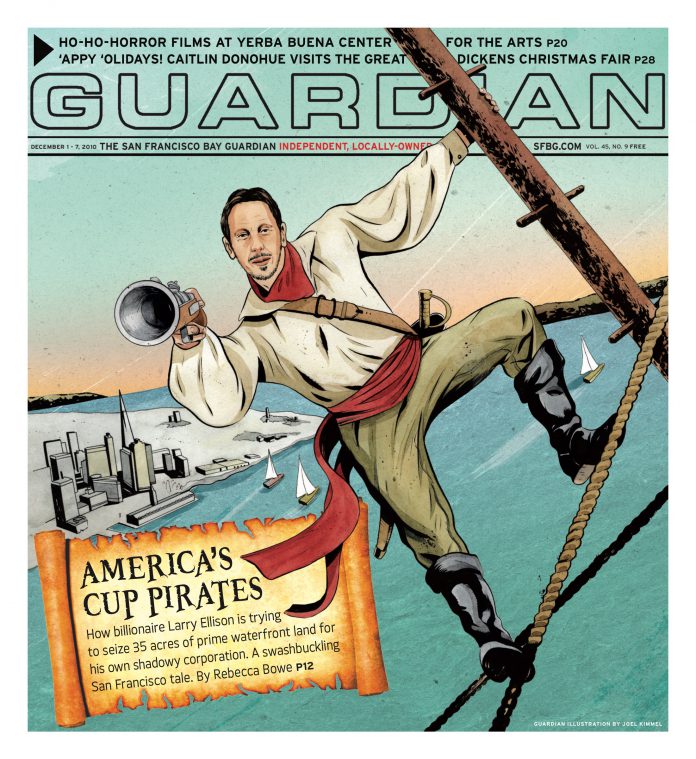

That’s exactly the way the deal that Mayor Gavin Newsom negotiated with Larry Ellison, the multibillionaire database mogul and yachtsman, is shaping up. A shadowy new corporation controlled by Ellison would get control of more than 30 acres of prime waterfront land worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The city could lose $42 million, and possibly as much as $128 million.

We don’t dispute the huge economic impact of holding an event that could attract more than 1 million visitors to the Bay Area. Those people will spend money in bars, restaurants, shops, and hotels. The waterfront improvements and increased tourism will create, according to economic reports, 8,840 jobs.

But as the Board of Supervisors budget analyst points out, those are not permanent, full-time jobs; much of the increased employment needs would be met by increased productivity (bartenders and waiters handling more customers than usual), overtime, and temporary jobs. And again: Most of the benefits will go to the private businesses in the tourist industry. The city’s increased tax revenue won’t be nearly enough to cover the expenses. Even if the America’s Cup group raises $32 million — and that’s not guaranteed in the deal — the city would still be down $10 million.

So in effect, San Francisco is preparing to spend $42 million of taxpayer money (and to forego as much as $86 million more by giving away waterfront land that could be developed) to benefit the sixth-richest person in the world, a new company he’s going to create and control, and the tourist-related businesses in town.

Oh, and to make it even juicier: the city is promising to seek state approval for Ellison to build condos or a hotel on the waterfront — something nobody else can legally do.

This doesn’t strike us as a terribly good deal.

It looks worse when you consider how the negotiations proceeded: The mayor and other city officials insisted they were scrambling to give Ellison everything he wanted to make sure that San Francisco beat out two other competitors. But as Rebecca Bowe reports on page 12, there were no other formal bids; Ellison’s team, based at the Golden Gate Yacht Club, was only negotiating with one city, San Francisco.

There are alternative proposals. The Telegraph Hill Dwellers Association wants to see the race complex moved from the Central Waterfront to the Northern Waterfront, and there may be ways of saving money. And Sup. Ross Mirkarimi points out that if Ellison wins the races in 2013 and comes back again the next time around, San Francisco could become what Newport, R.I., once was: a repeat host to an event that will bring more and more benefits as time goes on. That, however, involves a number of risks and variables that are far from certain at this point.

We’d like to know a lot more about what Ellison’s development plans are. We’d like to know who, exactly, will be running his new corporation that will get development rights for a couple of nice waterfront parcels.

But before the supervisors sign off on any deal, they need to set a bottom line: this can’t cost the city any net revenue. The San Francisco city treasury and local taxpayers shouldn’t be subsidizing an event created by and for the very wealthy.