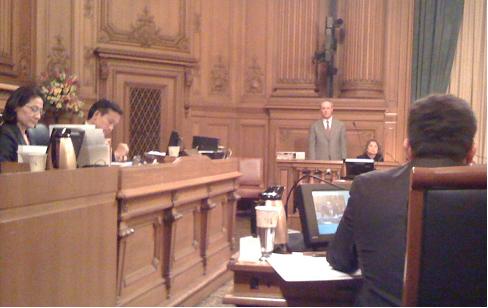

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a process for replacing Mayor Gavin Newsom last night after the progressive majority stuck together on a pair of key procedural votes and some parliamentary jousting provided a preview of the high-stakes power struggle that will begin Dec. 7.

Sup. Sean Elsbernd led the board moderates (Sups. Carmen Chu, Michela Alioto-Pier, Bevan Dufty, and Sophie Maxwell) in trying to dilute the voting power of the six progressives on the board (Sups. David Chiu, Chis Daly, David Campos, Eric Mar, Ross Mirkarimi, and John Avalos) and ensure they can’t vote as a bloc to choose the new mayor.

State conflict-of-interest rules spelled out by the California Political Reform Act and associated rulings prevent supervisors from voting in their economic interests, as becoming mayor would be. So Board Clerk Angela Calvillo and the Santa Clara County Counsel’s Office (legal counsel in the matter after our own City Attorney’s Office recused itself) created procedures whereby all nominees leave the room while the remaining supervisors vote.

But as Daly noted, clearing several supervisors from the room would make it unlikely that those remaining to come up with six votes for anyone. He also said the system would deny too many San Franciscans of a representative in this important decision and allow sabotage by just a few moderate supervisors, who could vote with a majority of supervisors present to adjourn the meeting in order to push the decision back to the next board that is sworn in on Jan. 11.

“The process before us is flawed,” Daly said.

So Daly sought to have the board vote on every nomination as it comes up, but Elsbernd argued that under Robert’s Rules of Order, nominations don’t automatically close like that and to modify a board rule that contradicts Robert’s Rules requires a supermajority of eight votes. Calvillo, who serves as the parliamentarian, agreed with that interpretation and Chiu (who serves as chair and is the final word on such questions) ruled that a supermajority was required.

Although some of his progressive colleagues privately grumbled about a ruling that ultimately hurt the progressives’ preferred system, Chiu later told the Guardian, “I gotta play umpire as I see the rules…We need to ensure the process and how we arrive at a process is fair and transparent.”

Nonetheless, Chiu voted with the progressives on the rule change, which failed on a 6-5 vote. But Daly noted that supervisors may still refuse nominations and remain voting until they are ready to be considered themselves, which could practically have the same effect as the rejected rule change. “If we think that’s a better way to do it, we can do it, but we don’t need to fall into the trap and subterfuge of our opponents,” Daly told his colleagues.

Elsbernd then moved to approve the process as developed by Calvillo, but Daly instead made a motion to amend the process by incorporating some elements on his plan that don’t require a supermajority. After a short recess to clarify the motion, the next battleground was over the question of how nominees would be voted on.

Calvillo and Elsbernd preferred a system whereby supervisors would vote on the group of nominees all at once, but Daly argued that would dilute the vote and make it difficult to discern which of the nominees could get to six votes (and conversely, which nominees couldn’t and could thereby withdraw their nominations and participate in the process).

“It is not the only way to put together a process that relies on Robert’s Rules and board rules,” Daly noted, a point that was also confirmed at the meeting by Assistant Santa Clara County Counsel Orry Korb under questioning from Campos. “There are different ways to configure the nomination process,” Korb said. “Legally, there is no prohibition against taking single nominations at a time.”

So Daly made a motion to have each nominee in turn voted up or down by the voting board members, which required only a majority vote because it doesn’t contradict Robert’s Rules of Order. That motion was approved by the progressive supervisors on a 6-5 vote.

Both sides at times sought to cast the other as playing procedural games, and both emphasized what an important decision this is. “This is without a question the most important vote that any of us will take as a member of the Board of Supervisors and one that everyone is watching,” Elsbernd said of choosing a new mayor.

So after the divisive procedural votes played out, Chiu stepped down from the podium and appealed for unity around the final set of procedures. He said that San Franciscans need to have confidence that the process is fair and accepted by all, and so, “It would be great if we have more than a 6-5 vote on this.”

As the role call was taken, Carmen Chu was the first moderate to vote “yes,” and her colleagues followed suit on a 11-0 vote to approve the process. At that point, the board could have begun taking nominations, but it was already 7 p.m. and both Daly and Chiu argued to delay that process by couple weeks.

“We owe it to ourselves and this city to have a discussion [of what qualities various supervisors want to see in a new mayor] before we get into names and sequestration,” Daly said.

He and other progressive proposed to continue this discussion to Dec. 7, but Elsbernd – who was visibly agitated by the discussion – suddenly moved to table the item (which would end the discussion without spelling out the next step), a motion rejected on a 4-7 vote, with Maxwell joining the progressives.

The discussion ended with a unanimous vote to continue the item to Dec. 7, when supervisors will discuss what they want in a new mayor and possibly begin the process of making and voting on nominations. Anyone who receives six votes will need to again be confirmed during the board meeting on Jan. 4, a day after Newsom assumes the office of lieutenant governor.