By Patrick Porgans and Lloyd Carter

news@sfbg.com

While Californians were held captive waiting for Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and the Legislature to agree on spending cuts and adopt a budget, state officials were throwing hundreds of millions of dollars down the drain and compounding California’s water crisis.

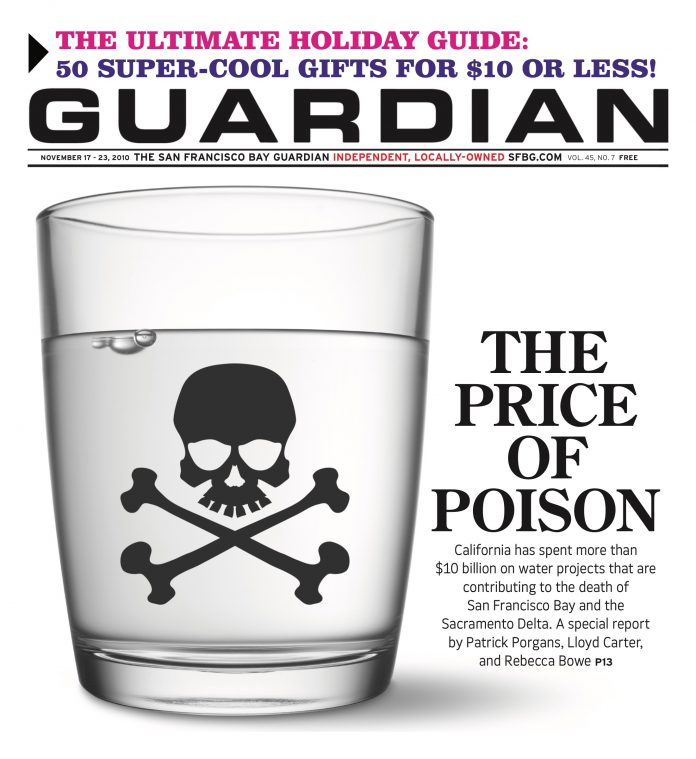

Water officials have wasted more than $10 billion and 35 years in extended delays in their failed attempt to carry out their legal mandates to protect the waters of the state and restore the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary. The result: water quality in the estuary is rapidly declining; fisheries are in crisis; and the proposed solution, an $11 billion bond act set for the ballot in 2012, will only make things worse.

The primary source of the water-quality crisis is a toxic mix of salt and chemicals discharged from lands irrigated by subsidized water delivered by the federal Central Valley Project to contractors farming on the arid west side of the San Joaquin Valley.

The salt comes from several sources. Irrigation water — particularly from the delta, where the water is somewhat brackish — contains salt. There also is salt and traces of much more toxic selenium in the soil. Industrial fertilizers add more dangerous chemicals to the mix. And since crops grown in the Central Valley don’t absorb much salt and the constant flushing with irrigation water leaches the selenium out of the soil, a nasty stew starts to build up.

This U.S. Geological Survey map shows a plan by federal and state regulators to divert toxic water more directly into the Sacramento Delta. All these diversion plans ignore the fact that poorly drained land isn’t suitable for farming.

If the irrigation water isn’t drained off, the salt buildup in the groundwater renders the land unusable to farming. In essence, farmers have been dumping the runoff water — laden with salt and selenium, along with mercury and boron — into the San Joaquin River, which carries it back into the delta and the bay.

All this is being done as the government declares its intent to save the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary.

How much salt are we talking about? According to a 2006 U.S. Geological Survey report, it amounts to about 17 railroad cars a day, each capable of carrying 100 tons of salt, as well as selenium and mercury. That’s 3.4 million pounds of salt a day being dumped in the lower San Joaquin River.

Of course, the river is a freshwater habitat, so all that salt damages plant and fish life.

Some experts say that part of the toxic stew is ultimately flushed out to sea, and the rest perhaps enters the aquatic food chain or at least degrades cleaner delta water.

As far back as the 1998, the state Water Board staff reported that salt loads in the valley were doubling every five years. Toxic salt-loading is not only taking its toll on the river and Bay-Delta Estuary, it’s draining the state treasury since myriad publicly funded programs for drainage, water quality improvement, fisheries restoration, and others continue to be financed with borrowed money from the deficit-ridden General Fund.

The water quality problem was identified as a potential crisis in the 1950s and has contributed to the pollution of a significant length of the 330-mile San Joaquin River. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 215.4 miles of the river are on the list of waterways so polluted they’re unfit to swim in. And some species of fish from the river aren’t safe to eat.

On a 1999 EPA map, the valley is the single largest “more serious water quality problem — high vulnerability” area in the nation.

Water officials, drainers, and the major environmental groups forged a deal in 1995 to permit the toxic drainage to continue until October 2010, at which time the discharges were to end. But that hasn’t happened; the water boards have approved a new target date for compliance (2019) and sanctioned continued dumping of toxic drainage. The train wreck in the making will be allowed to continue dumping and pumping toxic salts every day into the waters of the state for the rest of this decade.

The tons of toxics salts being discharged into the waters of the state are only the tip of the iceberg. An unfathomable amount of toxic salts are also being stored in the soil underground, contaminating groundwater basins throughout the valley.

State and federal officials have put a lot of faith in a federal Bureau of Reclamation project known as the Grasslands Bypass, which is designed to send contaminated agricultural water through a part of the old San Luis Drain (that once led to the contamination of the Kesterson Wildlife Refuge) into a San Joaquin tributary known as Mud Slough.

The Grasslands Bypass Project, begun in 1995, is operated by the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation. It reroutes subsurface agricultural drainage water around wetlands on its way eastward to the San Joaquin River.

Originally the agricultural runoff traveled through Salt Slough (a San Joaquin River tributary), which passed through wetlands on the way to the river. The Grasslands Bypass Project uses the San Luis Drain to reroute that runoff around approximately 100,000 acres of land between Firebaugh and Los Banos and into Mud Slough (another tributary of the San Joaquin River).

Carolee Krieger, president of the California Water Impact Network (C-WIN), says the Grasslands Bypass Project misses the point. The best solution, she said, is to stop farming altogether on the poorly-draining western valley along the San Joaquin River.

The project protects the wetlands but hurts the river itself. Dennis Lemly, research professor of biology at Wake Forest University in Winston/Salem, N.C., confirmed in December 2009 that the continuation of the Grasslands Bypass Project will cause a 50 percent mortality among juvenile Chinook salmon and Central Valley Steelhead in the San Joaquin River. Furthermore, the state water board lists both the Carquinez Strait and Suisun Bay, both downstream from the San Joaquin River, as “impaired” for their excessive selenium content.

At best, the bypass project can only slightly mitigate the damage. The only real way to resolve the discharge of the tons of toxic salts is to stop irrigating land that has known drainage problems.

In the early 1980s, the discharge of the toxic salts into the now-closed Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge, located in the San Joaquin Valley, was the site of one of the worst government-induced wildlife crises in American history. Several studies have since been conducted and numerous Band-Aid-type fixes have been implemented, costing taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. So far officials have failed to identify a viable cost-effective solution to the toxic agricultural drainage crisis and estimate a pilot program will cost at least $2 billion.

Meanwhile, the Legislative Analyst reported in 2008 that the state and federal government have spent $5 billion on projects to improve the Delta.

This is one of the ways your tax dollars fund the destruction of the San Francisco Bay-Delta ecosystem.

Patrick Porgans is a Sacramento-based water-policy consultant. Lloyd Carter, a former UPI and Fresno Bee reporter, has covered water issues in California for more than 30 years. For more information, go to www.lloydgcarter.com and www.planetarysolutions.org. Additional research was done by Noah Arroyo.