Under the benevolent neon rainbow of Twin Peaks Tavern, a bearded man with a battered trunk strolls up and addresses a group of people seated at café tables in the little plaza tucked beside the F-Market turnaround at Castro and 17’th. It’s the sort of thing that happens a lot in San Francisco, the difference in this case being that the figure is none other than Walt Whitman (robustly channeled by No Nude Men’s Ryan Hayes), and the assembled crowd a diverse group of Fringe Festival patrons,

Castro habitués, and curious bystanders sucked in by the moment. Average of build yet bold of purpose, this is not the “Old Father Graybeard” of Allen Ginsberg’s “A Supermarket in California”—but rather a younger, lustier Whitman, who perambulates easily about the crowd and speaks desire to the bustle of passerby and impatient streetcars.

This site-specific piece entitled “Boys Together Clinging: the Gay Poetry of Walt Whitman” brings to vibrant life the “Calamus” poem-cluster, contained within Whitman’s definitive tome Leaves of Grass. Written 150 years ago, the “Calamus” poems speak frankly of “manly attachment,” “athletic love,” and a multitude of “comrades”.

Walt speaks! Ryan Hayes channels in the Castro

Insinuating himself into his audience, the present-day incarnation of the poet grasped hands, caressed shoulders, chased after a hottie in a hoodie, a “passing stranger,” calling out after him: “I slept with you”. He is gentle, candid, sweetly-frustrated, threatening to drop allegiance to his poetry for his unnamed love. “I am indifferent to my own songs,” he confesses, but “determined to unbare this broad breast of mine, I have long enough stifled and choked.” His confession come to an end, he hoists his trunk once more, his burden, and prepares to follow the F-Market, and his desires, to the end of the line.

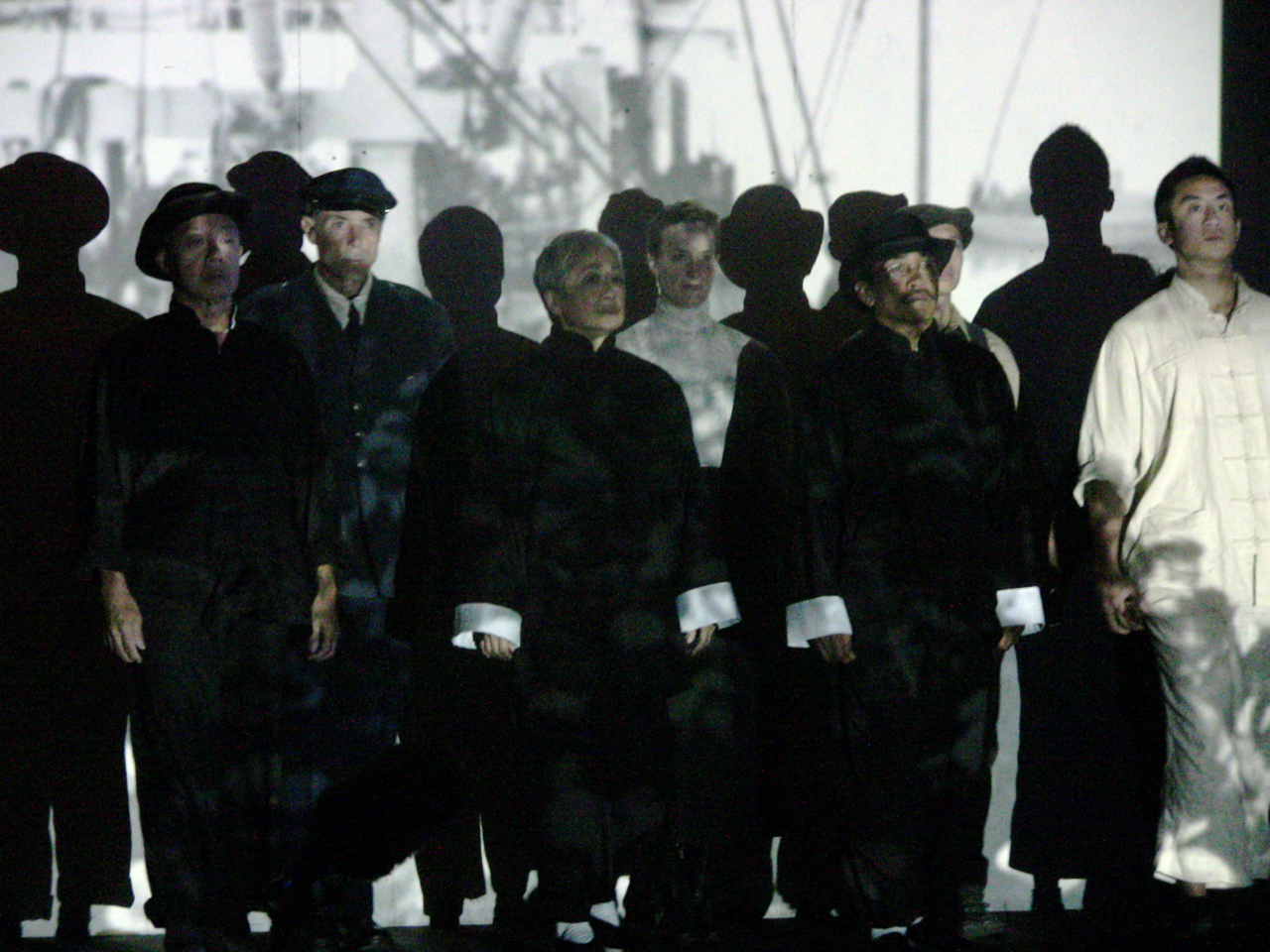

On the opposite side of town, another site-specific piece was also airing out some secrets. Genny Lim’s “Paper Angels” might have been written in 1980, and set in 1915, but the politics of the still-controversial 14th Amendment regarding birthright citizenship which permeate it are uncomfortably close to the present moment.

Set on Angel Island, (though performed more accessibly at Portsmouth Square, on the edge of Chinatown) “Paper Angels” follows the detention of seven Chinese immigrants, awaiting their release, or deportation. Because of the Chinese Exclusion act of 1882, many Chinese immigrants could expect to be turned back before ever setting foot past the Immigration Station, but thanks to a curious loophole—the fact that all of San Francisco’s birth and immigration records had been destroyed in the fires of 1906—a wave of “paper sons” were able to claim birthright citizenship by changing their identities to match those of families who had already been granted citizenship.

It’s a complex and painful history, told by NYC’s Direct Arts through a kaleidoscopic series of short vignettes against a backdrop of projections of the over-crowded barracks and anguished poetry carved into the walls by the incarcerated detainees. Though much more robust in terms of production values than “Boys Together,” both pieces shared a deliberate resonance with their chosen sites, the heartache of secrecy, the resolute power of poetry, and the transcendence of release.