Tredmond@sfbg.com

I went through the house the other day and sorted out all the old toys my kids never play with any more. They’re 8 and 11 now, so they’ve outgrown a lot of stuff. Some of it went to Goodwill, some of it went to friends who have younger children, some of it went out on the sidewalk with a “free” sign — and still, there was a pile left over.

Broken plastic. Shit nobody wants. Can’t be recycled. It went in the trash.

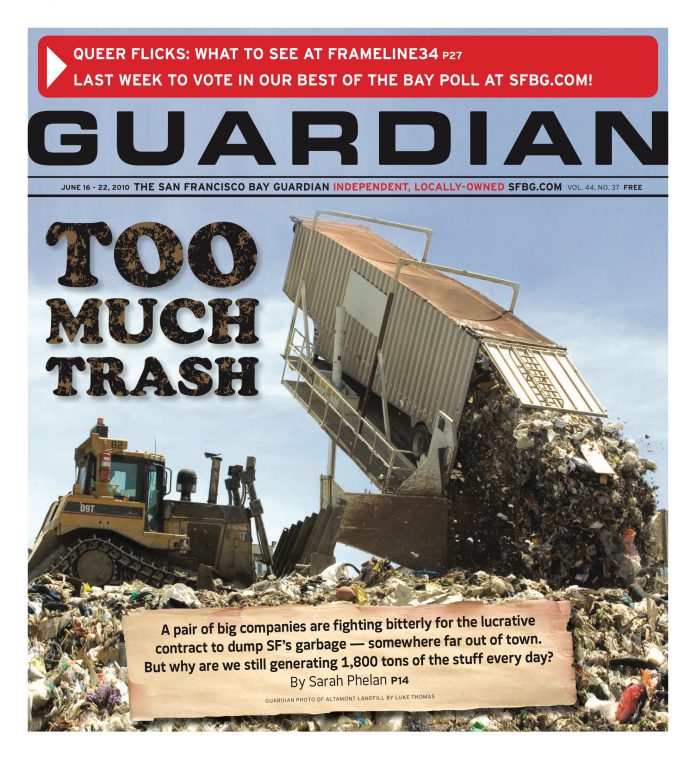

And now, as Sarah Phelan reports in this issue, it’s probably sitting in a landfill across the bay, taking up space and waiting a couple thousand years until it becomes the archeological remnants of our civilization. Stuff from the ancient world is valuable because it’s fragile, and there’s not much left; our society is leaving an excellent record. That plastic will never decompose.

And now two private companies are fighting for the right to pile up my trash in a landfill, either at Altamont or in Yuba County. It’s a high-stakes battle; there’s a lot of money in garbage. And it’s a little disturbing to realize that in San Francisco, the entire process of collecting, recycling, composting, and dumping our solid waste stream is controlled by private companies.

What if we actually succeed in reducing our waste stream to zero? What if we reach the point where we’re buying less, tossing less, reducing the 1,800 tons of crap that flows into landfills from SF every day? Isn’t that what we ought to be doing? And what interest does a private landfill owner, who makes money from my kids’ broken toys, have in seeing the flow of detritus — and thus the flow of money — cut off?

I’m not arguing that we municipalize the trash system (not today, anyway; let’s do electric power, cable TV, and Internet first). But while she was working on the story, Phelan kept telling me that the city ought to look at keeping all the trash in town. If you could see that horrible mountain of crap right out your window, maybe you wouldn’t throw so much of it away.

She was kidding, of course. Sort of.